We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

Fight for Bread: The Pentrich Revolution

In June 1817, hundreds of rebels gathered in rural Derbyshire and marched on London

"Every man his skill must try

He must turn out and not deny;

No bloody soldier must he dread,

He must turn out and fight for bread.

The time is come you plainly see

The government opposed must be."

- Jeremiah Brandreth

The year was 1817, and Britain’s aristocratic elite were jubilant.

The British empire had just emerged triumphant from the long struggle against revolutionary France.

After decades of international warfare and domestic repression, the emancipatory ideals of the French Revolution had been vanquished.

Class hierarchy and aristocratic opulence were, once again, safe and sound in Europe. The natural order of things was restored, and the impoverished masses were silent.

Or so it seemed…

Thomas Paine was one of many British radicals who were targeted by the government's anti-revolutionary crackdown

Click to view our Thomas Paine tea towel

Post-war Britain fell headlong into economic depression.

Breakneck industrialisation twinned with the demobilisation of the army and navy caused mass unemployment.

The massive national debt was being recouped by indirect taxation on day-to-day spending, and a tariff regime designed for the landowning aristocrats who still dominated British politics meant that food prices were sky-high.

If anything, the prospects for a revolution in Britain were higher now than they had been during the height of the French Revolution.

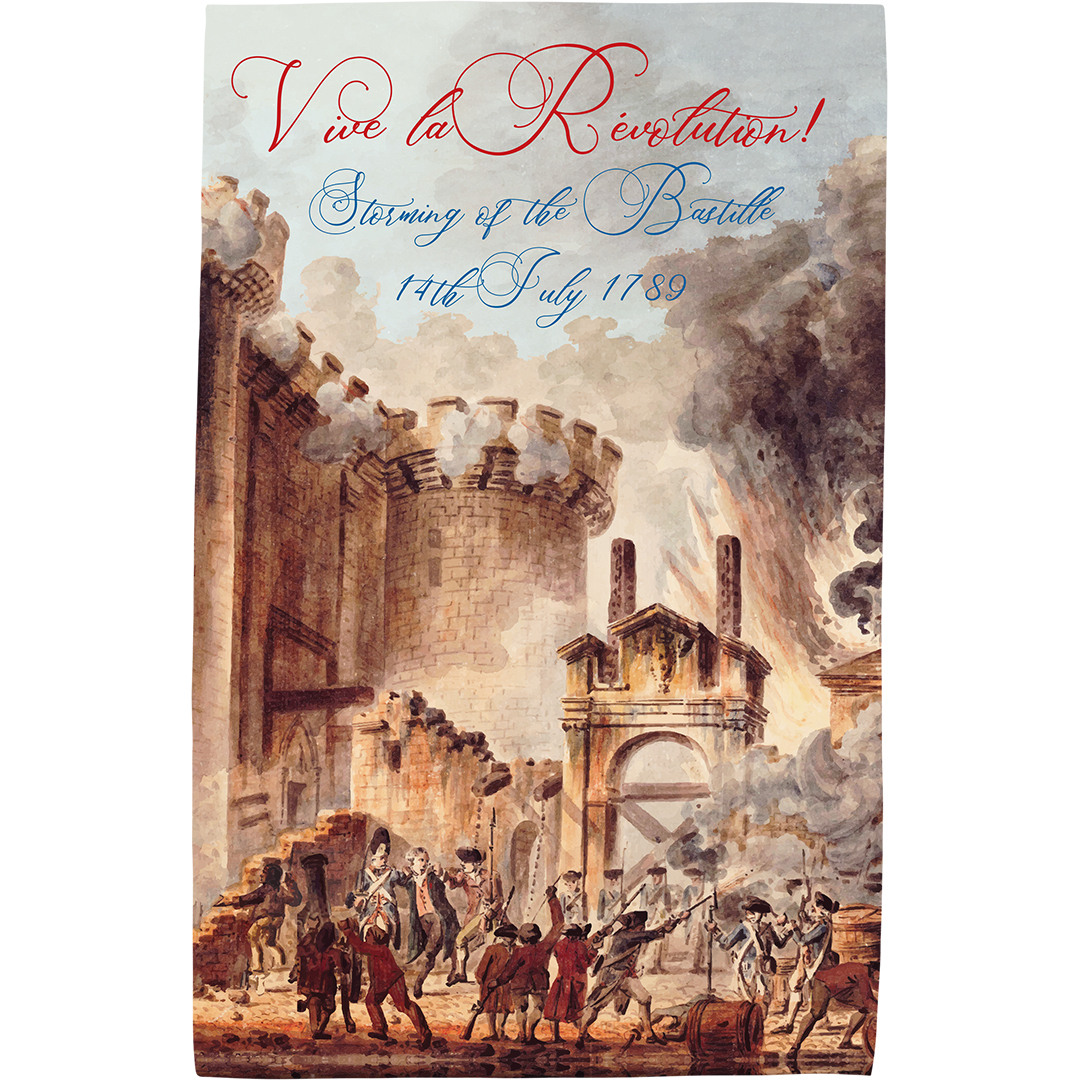

The Revolution may have been defeated, but the symbolic Storming of the Bastille continued to inspire radicals across the world

Click to view our Storming of the Bastille tea towel

Then, on 9 June 1817, just two years after the Battle of Waterloo, a revolutionary insurrection was launched in rural Derbyshire.

Between 200 and 300 men assembled in Wingfield, near Pentrich, and began to march on London.

They wanted the abolition of the National Debt, to bring an end to the crippling taxation of the poor in England, and they wanted the democratising parliamentary reforms then being proposed by the MP Francis Burdett.

These Derbyshire rebels were the victims of early industrial capitalism and inequality in Georgian England.

Artisans made jobless by the mechanisation of the textile sector, and demobilised veterans of the wars against France, cast aside by a state which no longer had use for them.

One of the main leaders was Jeremiah Bandreth, an unemployed artisan from Nottingham. Another was William Turner, an ex-soldier.

The rebellion in Pentrich set out after dark on 9 June.

They had learned that another revolutionary column was advancing from the north. The two groups would link up, then march together on London to demand social and political justice for a country in dire need of it.

Improvised weapons were supplied by Isaac Ludlam, a bankrupted farmer with a small quarry nearby. And more rebels were mobilised from local villages.

Jeremiah Brandreth was the leader of the Pentrich Revolution, and was among the last people to be beheaded by axe in Britain

Click to view our Jeremiah Brandreth tea towel

But the Pentrich rebels were walking into a trap.

The allied column of revolutionaries was a lie, spun by an agent provocateur, sent by the Home Office to help disrupt and expose the enemies of the status quo.

When the rebels marched into Giltbrook, they were met by a force of soldiers. Most of the unarmed and untrained men dispersed or were arrested.

In all, 85 rebels were imprisoned.

14 men were deported to the penal colonies, and three of the leaders, including Bandreth, were tried by a rigged jury of landowners, condemned to death for treason, and executed.

Reformers in London condemned the government for such a draconian response, and for its nefarious use of political spies among the general public.

There was no getting around the fact that the Pentrich Rebellion had been an ignominious failure: short, clumsy, and unsuccessful.

Yet it was also a sign of bigger and more disruptive radicalism to come. Because the British state and its aristocratic and industrial allies, try as they might, could not keep the masses silent.

So long as injustice remained in Britain, there would be popular resistance to it.

Pentrich was one of the first notes in an entire symphony of post-Napoleonic radical politics in the British Isles, from the thousands of workers who rallied and died for democracy at Peterloo to the hundreds of thousands of Chartists who rocked British society to its very core.

Mighty oaks from little acorns grow.