We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

For the Benefit of Humanity: The Life and Work of Alexander Fleming

The story of Alexander Fleming and the discovery that changed medicine forever...

There are now Radical Tea Towels of each of the top three ‘Greatest Scots’, at least as voted in 2009: Robert Burns, William Wallace, and our newest addition, Alexander Fleming.

On the surface, the 1945 Nobel Prize-winner in Medicine may not seem an obvious political radical.

But Fleming’s work was as much social and humanitarian as it was scientific.

And today, almost a hundred years after his greatest discovery, we are celebrating that humanitarian legacy.

On this day in 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, the world's most widely-used antibiotic

Click to view our Alexander Fleming tea towel

Born on a farm in Ayrshire in 1881, Fleming studied down in London and went on to lecture in Bacteriology at St Mary’s Hospital Medical School in Paddington.

During the Great War, Fleming took a break from his research work and served as an officer in the Royal Army Medical Corps, saving the lives of wounded soldiers fighting in France.

It was during this time that Fleming made his first major advances in the field of Bacteriology.

Caring for soldiers on the Front, he realised that the antiseptics being used were doing more harm than good, killing off the natural bacteria which help the human body to counteract deep wounds.

Once back home, Fleming discovered lysozyme, an antimicrobial protein which makes up part of our natural immunity – a discovery which instantly established his reputation as a respected Bacteriologist.

But of course, it was Fleming’s discovery of penicillin – one of the most important medical discoveries of the 20th century – which would firmly establish his place in the history books:

“One sometimes finds what one is not looking for. When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionise all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.”

Like Fleming's discovery of penicillin, Alan L. Hart's tuberculosis research helped to save millions of lives

Click to view our Alan L. Hart tea towel

In the late summer of 1928, he was studying the properties of staphylococci bacteria. Then he went on a family holiday to Suffolk…

Like Einstein, Fleming was a very untidy man, and he hadn’t cleaned his lab before he left. When he returned from Suffolk, he found a culture of staphylococci had become contaminated by a fungus.

Immediately around the fungus, the bacteria had been destroyed. “That’s funny,” Fleming observed.

He isolated the fungus and found that it contained a powerful antibacterial substance. In March 1929, he named it ‘penicillin’ – a name derived from a plant of the genus Penicillium.

But Fleming’s work – like

Van Gogh’s now-famous paintings – wasn’t immediately appreciated. Unable to suggest any viable means to mass produce penicillin, its significance seemed limited at first.

Thankfully, for Fleming and the world, we didn’t have to wait until after his death for people to realise the gravity of his discovery.

In the late-1930s, a team at Oxford University led by Edward Abraham and Ernst Boris Chain were able to identify the structure of penicillin. This meant that, with enough resources, the drug could be mass produced.

And, for once, there were enough resources. With the Second World War raging on, the War Cabinet in London was persuaded to invest in the project.

Things moved so quickly that mass produced penicillin was ready in time for D-Day in 1944.

Thousands of Allied soldiers were saved by Alexander Fleming’s discovery. Though indirectly, Fleming’s work played a significant role in defeating the scourge of Nazism in Europe.

But penicillin, the first antibiotic, wouldn’t just be used to treat wounded soldiers during war: it would be used to treat civilians too. And Fleming was concerned about the early signs of how it would be used.

Like Nye Bevan, Alexander Fleming firmly believed that medical advances should be used for the benefit of humanity, not for profit

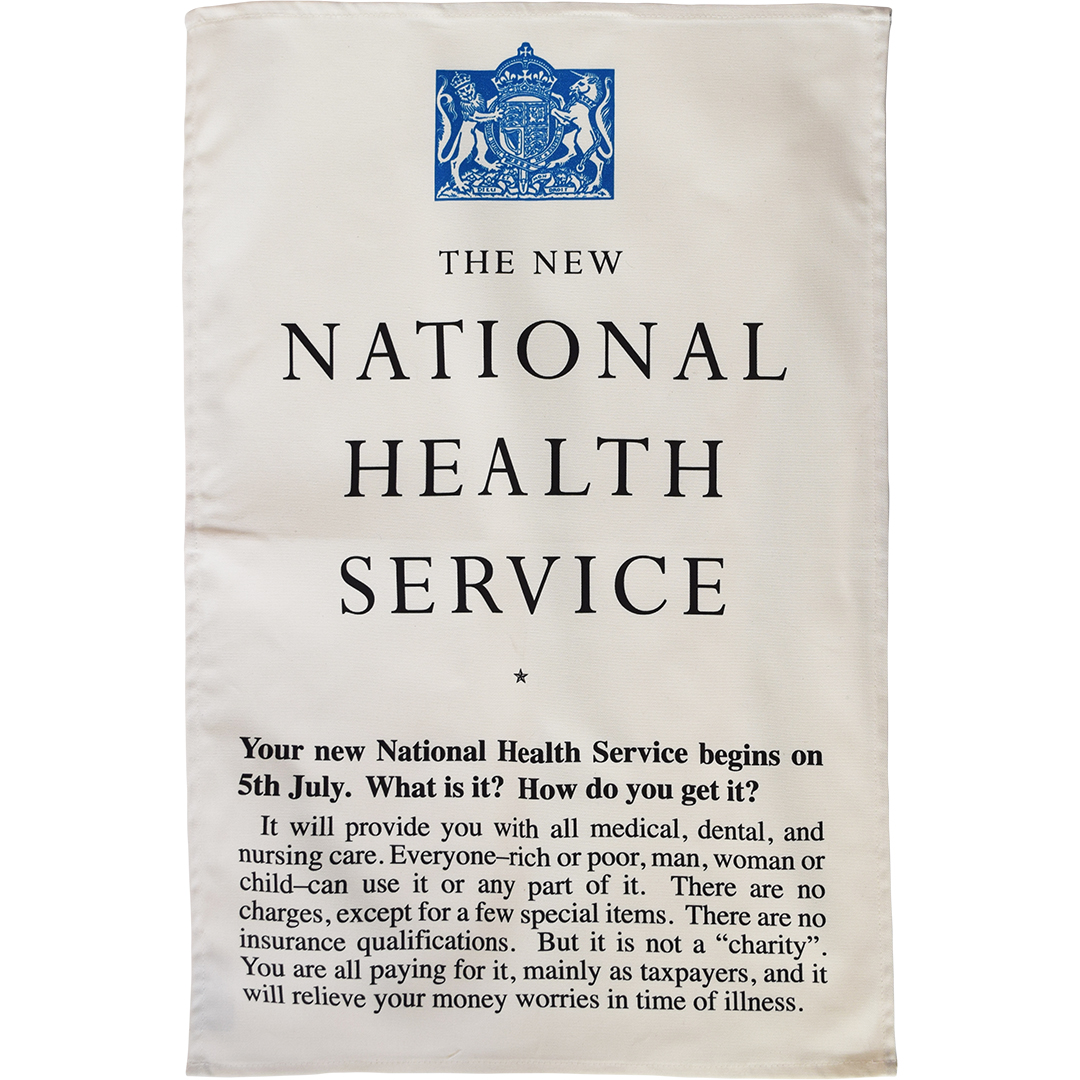

Click to view our National Health Service tea towel

When he heard that U.S. pharmaceuticals were trying to patent the mass production method for the drug, Fleming exclaimed:

“I found penicillin and have given it free for the benefit of humanity. Why should it become a profit-making monopoly of manufacturers in another country?”

This was a time of great change in healthcare systems across Europe: the UK's National Health Service was just coming into being, and politicians were finally discussing the universal right to a healthy life.

Alexander Fleming seems to have been plugged into this radical current. How dare people try to monetise his life-saving drug?

Penicillin, he realised, wouldn’t be a great humanitarian achievement if access were limited by the ability to pay.

Even to this day, that principle – that there should be no card-machine between you and the medical care you need to survive and thrive – still needs to be fought for.

Fleming was more than just a discoverer of antibiotics. He cared about how they should be used – freely, not for profit, but for people.