We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

Free from the Alps to the Adriatic: The Italian War of Independence

How the revolutionary fervour of 1848 turned into a full-blown War of Independence

In 1848, everything everywhere happened all at once.

Reactionary European leaders – the Tsar of Russia, the Emperor of Austria, the King of Prussia – thought that popular politics had been put to bed.

The French Revolution of the 1790s had been defeated. All was calm.

But it wasn’t as simple as that.

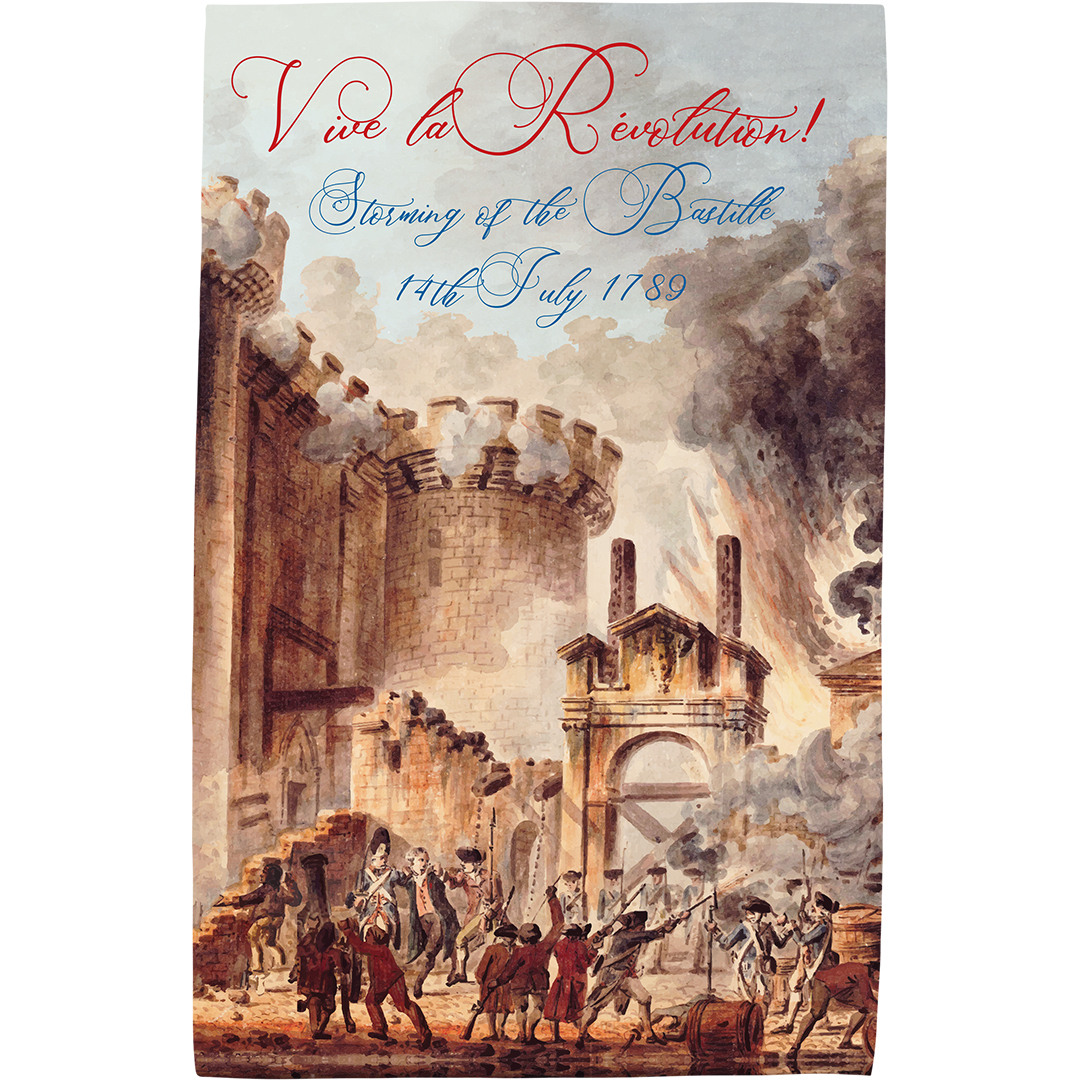

The great promise of the French Revolution had collapsed into the French Revolutionary Wars and the Reign of Terror

Click to view our Storming of the Bastille tea towel

A whole generation, all across Europe, had grown up in the shadow of the 'Age of Revolution' - not in fear of its message, but in awe of it.

From Paris to Palermo, via Poland and Prussia, there were countless young radicals who still dreamt of popular sovereignty and constitutional government instead of despots ruling by “divine right.”

All of this came to a head in 1848.

It kicked off in Paris, of course. The French were sick of their restored monarchy, so they brought back the Republic.

But as usual with Radical History, things didn’t stop there.

What had started in France began to spread: Berlin, Vienna, Budapest. Popular uprisings were happening everywhere, for constitutional government and democratic rule.

In Britain, the Chartists surfed the 1848 wave.

And on the Italian peninsula, the impact was even more dramatic. There, the people did not just want liberty – they wanted independence, too.

In April 1848, the Chartists organised a mass meeting of 150,000 people on Kennington Common to demand electoral reform

Click to view our Chartist Demonstration tea towel

The unified Italian nation-state – Italy as we know it – did not exist until the 1860s.

As of 1848, the Italian Peninsula hadn’t been unified under one government since the Roman Empire.

For centuries, it had been a patchwork of independent republics and kingdoms: Venice, Naples, the Papal States, and so on.

After Napoleon was defeated in 1815, the Great Powers of Europe ‘settled’ the Italian question so that the south of the Peninsular plus Sicily was ruled by the strangely-named ‘Kingdom of the Two Sicilies’, the middle was ruled by the Pope in Rome, and the north-west and Sardinia were ruled by the ‘Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia.’

But the rest of northern Italy, including the major cities of Milan and Venice, was given to Austria. I guess Europe’s reward for getting rid of Napoleonic imperialism was… more imperialism?

So, when the revolutionary wildfire which had started in France reached Italy a month later, a few tablespoons of national liberation were mixed in with all the republican fervour.

The people rose up across the Peninsula and neighbouring islands.

The more solidly ‘Italian’ monarchs in Naples, Rome, and Turin were forced to agree to new constitutions, limiting their power and giving more voice to the people.

But in the territories occupied by Austria, a constitution wouldn’t be enough. They wanted independence, too.

Inspired by the pan-European revolutionary fervour of 1848, Marx and Engels published The Communist Manifesto

Click to view our Karl Marx tea towel

On 18 March 1848, the ‘Five Days of Milan’ began: a huge popular revolt against the Austrian garrison.

The Austrian Emperor was already trying to fend off revolutions in Hungary and Vienna itself – revolution really was all over the place.

So the Milanese won. On the fifth of the Five Days, the Austrian troops pulled out of the city.

Taking their cue from Milan, the Venetians then declared independence from Austria as the ‘Republic of San Marco.’

The Austrian Empire was tumbling down. It really ought to have collapsed there and then.

Seeing the north of Italy fighting for its freedom, Charles Albert, the constitutional monarch of Piedmont-Sardinia, declared war on Austria.

It was now, officially, an Italian War of Independence.

All Italians seemed to be uniting for the struggle. Troops were sent north by the Pope and Naples to help fight the Austrians. And famous republican radicals like Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini came home to fight.

Over the summer of 1848, the various Italian armies and volunteers had the Austrians on the back foot.

But it wasn’t to last. The Pope soon abandoned the war, not wanting to antagonise Catholic Austria. As did the King of the Two Sicilies, who’d never been enthusiastic about constitutional rule anyway.

With the rebellions elsewhere in the Austrian Empire under control, reinforcements were sent to Italy, and gradually retook the region.

Venice and Milan eventually fell in the summer of 1849. And Piedmont-Sardinia surrendered.

The British Historian GM Trevelyan called 1848 the ‘turning point at which modern history failed to turn.’

The new French Republic was overthrown by Napoleon’s nephew. Hungary was reconquered by Austria and Russia.

And in Italy, the First War of Independence, for all of its radical heroics, was lost.

But the toil and sacrifice was not forgotten. Divided as they were, the Italian peoples had enjoyed a taste of freedom.

The Austrian empire in Italy, and the other absolute monarchs too, were living on borrowed time.