We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

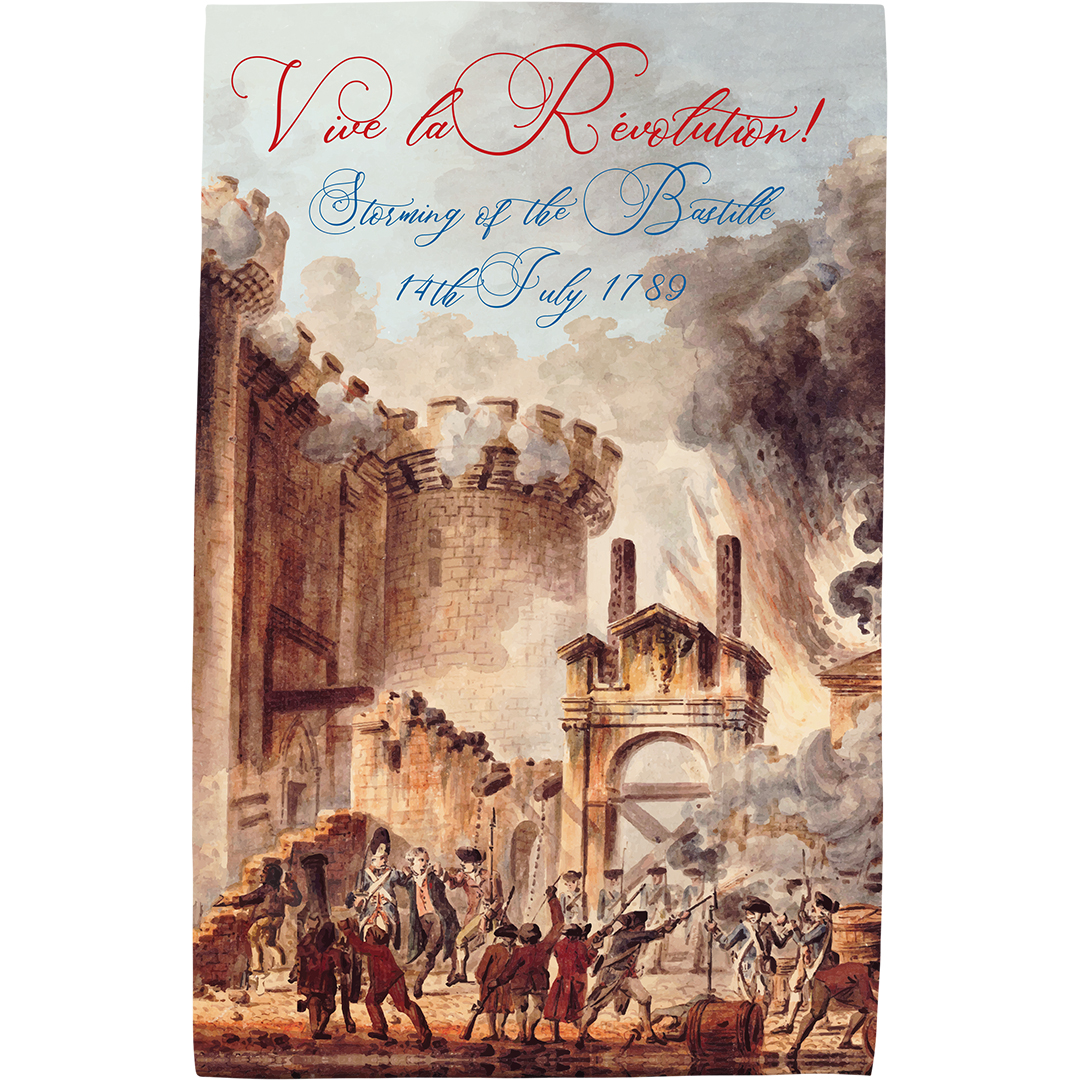

It's a Revolution: The Storming of the Bastille

How the people of France captured a Parisian prison and brought down the French monarchy

Martin Luther King Jr. once said that a riot is the language of the unheard.

For centuries before 1789, politics in the Kingdom of France concerned itself with kings and noblemen.

The common people, on the other hand, were counted as nothing – and the same was true across Europe.

It wasn’t that the masses were blindly submissive to their exclusion. Bread riots and peasant revolts – like the French

jacqueries – were a regular occurrence.

There were even a few organised political movements by the working classes, like the

Levellers and Diggers during the English Revolution.

But it wasn't until the Parisian masses stormed the Bastille prison that the people entered into European politics in such a way that they could never be expelled again.

The Storming of the Bastille is seen as a pivotal moment at the start of the French Revolution

Click to view our Storming of the Bastille tea towel

It was the summer of 1789, and the constitutional crisis in Bourbon France had been going on for several months.

Louis XVI had called the Estates General of the Realm to authorise the tax reforms needed to save the monarchy from financial ruin.

But things weren’t going to plan for the King.

He had wanted the three Estates – clergy, nobility, and commoners – to rubber stamp his fiscal measures and go home.

But the Third Estate – the common people – wanted something in return.

In June 1789, members of the Third Estate began to call themselves the ‘National Assembly’ – they did, after all, represent the vast majority of the French population.

They also took the famous

Tennis Court Oath, a promise not to disband until France had a new constitution.

Reactionary nobles close to the King became nervous.

They began to take measures to prepare for a coup. Frontier garrisons of the Royal Army – made up of Swiss and German mercenaries – were called back to Paris.

The radical writings of Thomas Paine played a key role in both the American and French revolutions

Click to view our Thomas Paine tea towel

Then, on 11 July, Louis dismissed the popular finance minister Jacques Necker, and filled his Cabinet with hardline aristocrats.

News of this reached Paris the next day.

The people sensed a move to crush their revolution before it could even begin – and they weren’t going to let that happen.

Revolutionaries gathered at the Palais-Royal in Paris to discuss their next steps. There, a young journalist named Camille Desmoulins stood up on a table and declared:

“Citizens, there is no time to lose; the dismissal of Necker is the knell of a Saint Bartholomew for patriots! This very night all the Swiss and German battalions will leave the Champ de Mars to massacre us all. One resource is left: to take arms!”

Saint Bartholomew was a reference to the organised massacre of thousands of French Protestants in 1572. Revolutionary Paris believed it was now, in 1789, time to fight or die.

There were mass protests in Paris on the 12 July, attacking royal offices. The French soldiers in the city did nothing to intervene – perhaps because they supported the revolutionaries.

The next day, a citizen’s militia was formed, and the

Marquis de Lafayette elected its commander.

But if revolutionary Paris was to defend itself, it would need weapons.

Victor Hugo's father was an ardent supporter of the French Republic, enlisting in the Revolutionary army at the age of fourteen

Click to view our Victor Hugo tea towel

On 14 July 1789, the Hôtel des Invalides had been seized by the people. Thousands of muskets were found, but no gunpowder.

The powder had been hurried away to a more secure location: the Bastille.

An historic symbol of royal tyranny in France, where political dissidents had been thrown away to suffer and die, the Bastille was now largely disused.

But it was still a heavily fortified building, with a garrison of about 100 troops standing guard.

By mid-morning, the Parisian masses had gathered to demand the surrender of the fortress and the gunpowder within.

After hours of unproductive talks, the crowd tried to storm the fortress at 13:30.

Bloody fighting ensued. But with the support of mutinous French Guardsmen, the people inevitably won out, taking the Bastille at 17:30.

When Louis XVI heard about it the next day, he asked the Duke of La Rochefoucauld:

“Is it a revolt?"

The Duke’s answer went down in history:

“No sire, it’s not a revolt; it’s a revolution.”

Louis backed down.

He withdrew the frontier troops from Paris, recalled Necker, and allowed a Third Estate deputy to be made Mayor of Paris.

The aristocratic elite which had so long had the run of France was beat. Not by the hired soldiers of some foreign aristocratic elite, but by the French people themselves.