We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

Europe's Revolutionary Democrat

Lajos Kossuth rose up against the Habsburg Empire and became a bellwether of democracy in Europe

"The spirit of our age is Democracy. All for the people, and all by the people. Nothing about the people without the people – That is Democracy!"

In 1851, Lajos Kossuth was the most famous revolutionary in the world.

He was also a failure.

Hungary, ruled by the Austrian Empire for centuries, had risen up for independence in 1848.

Kossuth, a Hungarian journalist and political agitator, had led the revolutionary government.

Kossuth's rebel armies held off the Austrians, and he declared Hungary an independent nation-state in April 1849.

But the Austrian Empire wasn't alone.

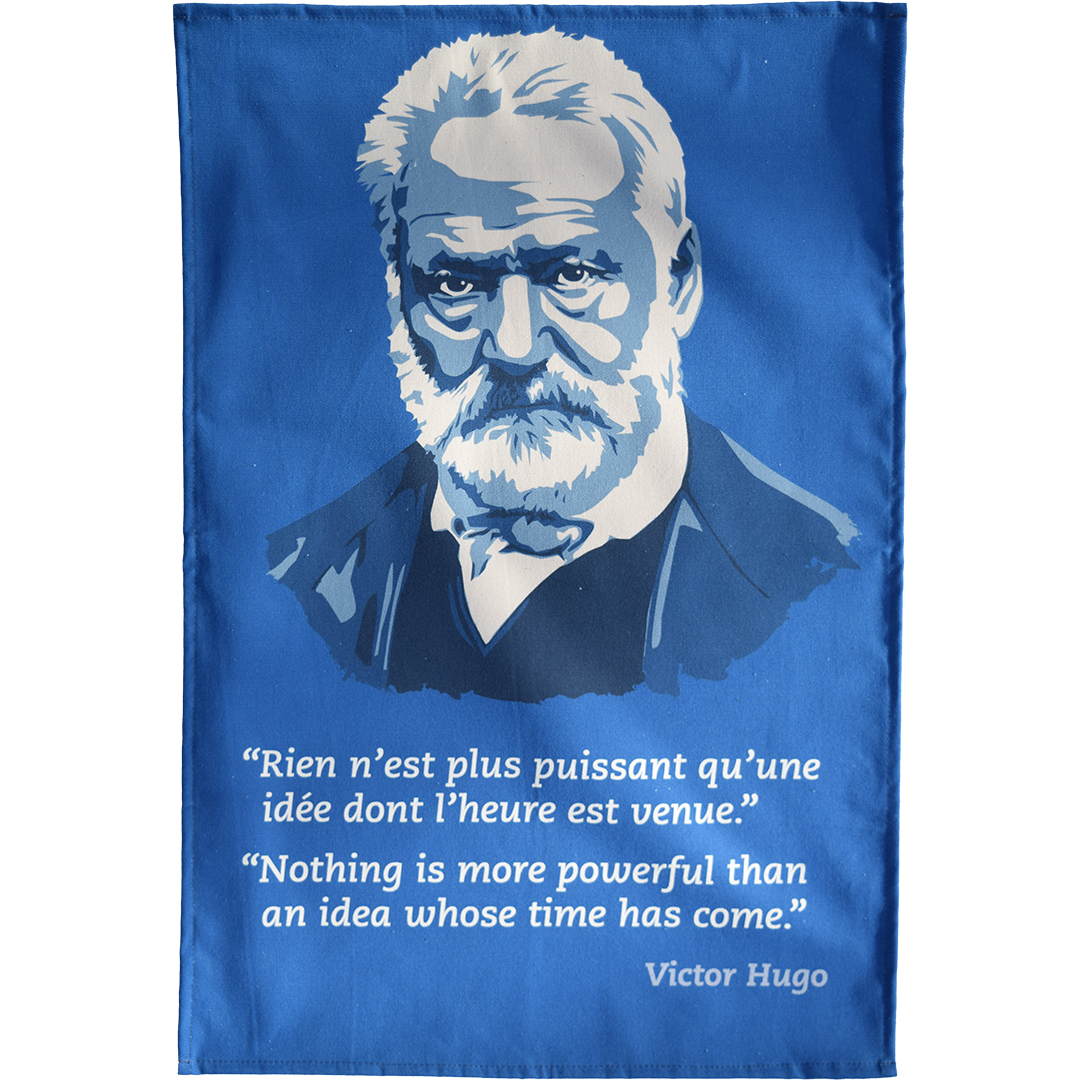

European radicals like Victor Hugo pushed for widespread democratic change in 1848

Click to view our Victor Hugo tea towel

Russia, the bastion of reactionary politics in nineteenth-century Europe, sent reinforcements. The Hungarians didn't stand a chance.

Kossuth was forced to flee into exile in the Ottoman Empire. He'd never return to Hungary.

But that wasn't the end of Kossuth's revolutionary career. Far from it.

Although the reactionary powers had prevailed, Kossuth didn't give up on the dream of a democratic and independent Hungary.

Among the several democratic revolutions which had broken out across Europe in 1848, Hungary was not alone in being defeated. All of them were.

But the

1848 revolutionaries held in common a "never say die" attitude. They refused to accept defeat, and continued to agitate in exile.

Kossuth found a supportive public in both Britain and the U.S.

Radicals in both countries, especially among the organised working class, had watched in delight and then horror at the rise and fall of the 1848 Revolutions.

The working-class Chartist movement had for years been calling for democracy by the time of Kossuth's visit to Britain

Click to view our People's Charter tea towel

Kossuth came to Britain for a few weeks in October 1851.

He'd become a living martyr of the revolutions in Europe, and was met by huge crowds of supporters across England.

Kossuth gave fiery speeches to trade unionists in Islington and Camden, calling on Britain to support the independence of oppressed nations in Europe.

In December, Kossuth sailed across the Atlantic to New York.

New Yorkers gave the Hungarian a similarly enthusiastic reception. “Kossuth Mania” was spreading.

He met the President at the White House, and became the second non-American ever to address a Joint Session of Congress. The first had been the

Marquis de Lafayette.

Political rallies were held across the United States to celebrate Kossuth and his democratic ideals, including one organised by the Illinois statesman,

Abraham Lincoln.

Kossuth spent much of the next decade trying to persuade foreign governments to actively support Hungarian independence from Austria.

But this often led to ill-judged moral compromises for little reward.

While in the U.S., Kossuth remained silent on black slavery to curry favour with the government.

Abolitionists were rightly outraged.

After leaving the U.S. in July 1852, Kossuth tried to exploit great power rivalries in order to convince someone to send a liberating army to Hungary.

There seemed a chance that the reactionary Emperor of France, Napoleon III, might support Hungarian independence in the late 1850s, when France was at odds with Austria.

But Kossuth should already have learned that Emperors were not to be trusted.

Future President Lincoln organised a rally celebrating Kossuth and his ideals

Click to view our Abraham Lincoln tea towel

Napoleon made peace with the Austrians without any concern for Hungary.

In exile, Kossuth was at his radical best when he put his faith in popular power rather than the self-interest of princes.

In 1860, Kossuth gave support to Giuseppe Garibaldi's popular struggle to liberate Italy. A Hungarian Legion served with Garibaldi's "Redshirts" as they fought in Sicily.

Kossuth also worked with another Italian revolutionary, Giuseppe Mazzini, to organise revolutionary exiles from across Europe to campaign for a democratic future for the whole continent.

Kossuth died in 1894, still in exile.

It was by now over four decades since the Hungarian independence struggle had been crushed on the battlefield.

Hungary was still subject to the Austrian Habsburgs, and Russia still loomed over Eastern and Central Europe, eager to crush any revolutionary project there.

But Kossuth had never given up.

Until the discovery of a recording of Helmuth von Moltke in 2012, Lajos Kossuth was the earliest-born person to have had their voice recorded. The recording was from a speech he gave in 1890 in Turin.

What was the speech about? His continued commitment, despite all the setbacks, to democracy and independence.