We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

Radical Time Travel: When William Morris Met John Ball

On 13th November in 1886, the Victorian socialist William Morris published the first instalment of A Dream of John Ball...

During the nineteenth century, as capitalism conquered the world, people began to long for a pre-industrial past.

In England, it was often aristocrats, as reactionary as they were rich, who fantasised about the Middle Ages.

They dreamt of a time when the masses supposedly ‘knew their place’ and deferred to men who happened to belong to random aristocratic families.

But some left-wing radicals also looked back to the medieval world, and they saw something very different.

In A Dream of John Ball, William Morris dreams himself back to the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 where he meets the radical priest John Ball

See the Dream of John Ball tea towel

On this day in 1886, William Morris began publishing A Dream of John Ball in serialised form in his socialist journal Commonweal.

It was a fantastical, first-person account of Morris dreaming himself back to medieval Kent at the time of the

Peasants' Revolt of 1381.

Morris looked to the Great Rising as a model of popular resistance to economic injustice, and he used the story to present the medieval world created by peasant rebels in England as a fairer society than the modern one of industrial capitalism.

It's not surprising that the Victorian working class and their political supporters like Morris remembered the pre-capitalist world fondly.

Before industrial capitalism really got underway in the eighteenth century, ordinary workers often owned their own land and were, in a more substantive sense, free and autonomous.

Then the expansion of commercial agriculture stole poor farmers’ land through state-backed violence and enclosures forcing rural workers into the new cities where they had to sell their labour simply to survive.

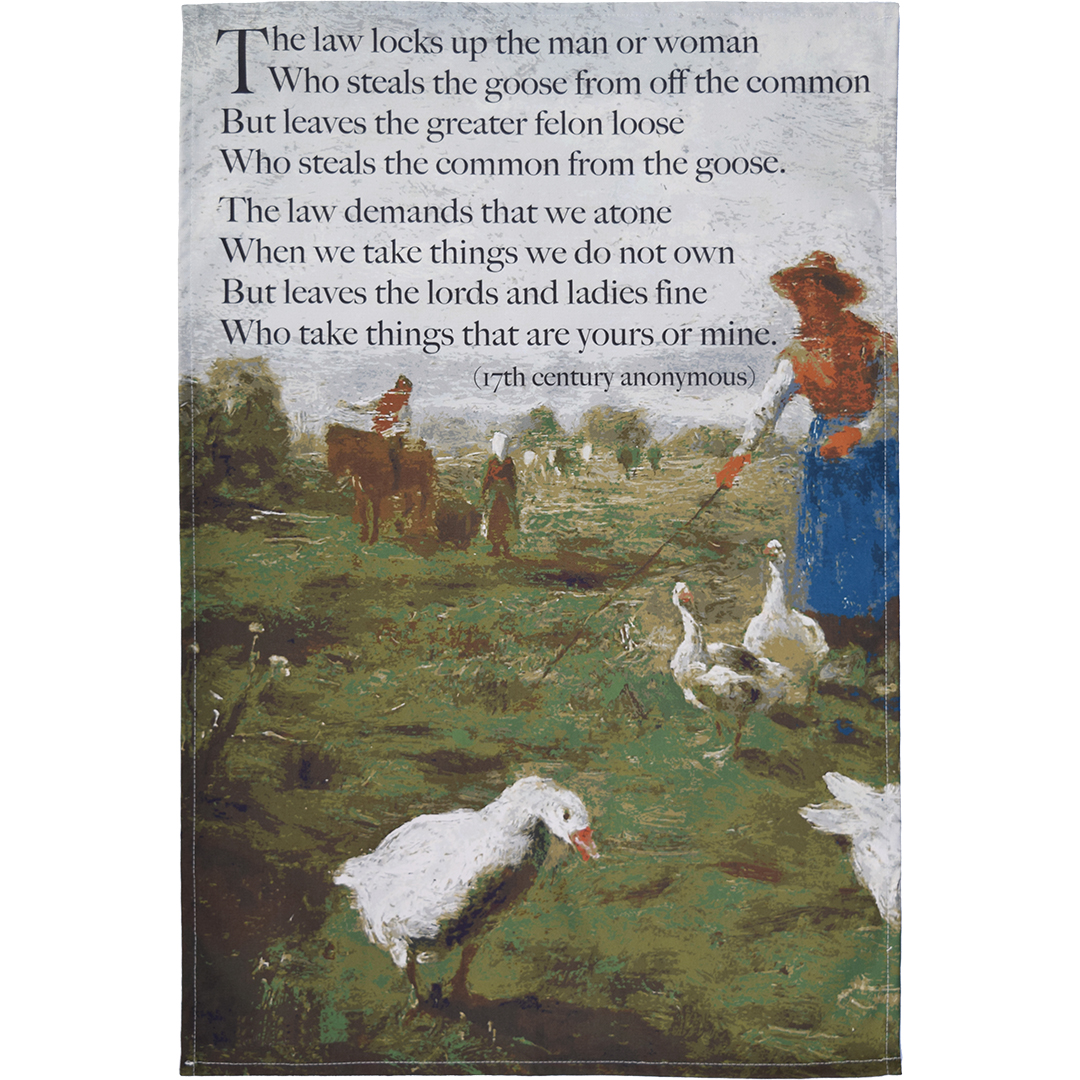

This seventeenth century rhyme condemns the appropriation of common land by aristocrats, which turned peasant farmers into wage workers

See the Enclosures Rhyme tea towel

In A Dream of John Ball, William Morris dreams of a time before this massive dispossession of labourers in England.

His time-travelling narrator first arrives in rural Kent as the peasant rebels are mobilising to march on London.

He sees the people of Kent rallied by the radical priest John Ball, who points out that there is no justification in Christian scripture for the gross material inequalities between so-called noblemen and those they enserfed.

Ball’s rebel troops march under an image of the Garden of Eden which reads:

“When Adam delved and Eve span

Who was then the gentleman?”

Ball tells the gathering that, once they overthrow serfdom, everyone will be their own master. Everyone will be free.

Wat Tyler and the rebels demanded a reduction in taxation, an end to the system of serfdom and the removal of the King's senior officials

See the Peasants' Revolt tea towel

It was a cry of rebellion in the language of Christian equality. Ball wanted the people of England to fight for this ideal.

“…as one day the saints shall call you to the heavenly feast, so now do the poor men call you to the battle.”

After the first skirmishes of the revolt, Morris imagines a meeting between himself and John Ball in which – with his historical foresight – he tells Ball that the Peasants’ Revolt will be crushed by the King. But only in the short term.

Morris tells Ball to look forward to a later medieval era in which serfdom declines and craft guilds become stronger, protecting ordinary artisans.

The medieval version of trade unions will bring freedom and prosperity to the workers, Morris explains.

What John Ball ought to worry about instead, Morris tells him, is what comes later: industrial capitalism.

In the nineteenth century, Morris explains to Ball, while the working man in England is now legally free, he is landless and forced to sell his labour to capitalists in order to survive.

John Ball is puzzled: such a man, he says, “may well do what thou sayest and live, but he may not do it and live a free man.”

Freedom means material autonomy. That is, freedom to refuse to work for someone else without having to worry about the next meal, or where to sleep.

Through this imagined meeting of a medieval priest and a Victorian socialist, William Morris presents his emphatic denunciation of industrial capitalism.

Industrialisation was not ‘progress,’ as the ideologues of the new status quo claimed, but a step backwards.

A peasant in the 1380s could see that such a society, in which most people had to constantly sell their labour to the rich and powerful in order to (just about) survive, was utterly unfree.

William Morris was pushing his readers in the 1880s to see this, too.