We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

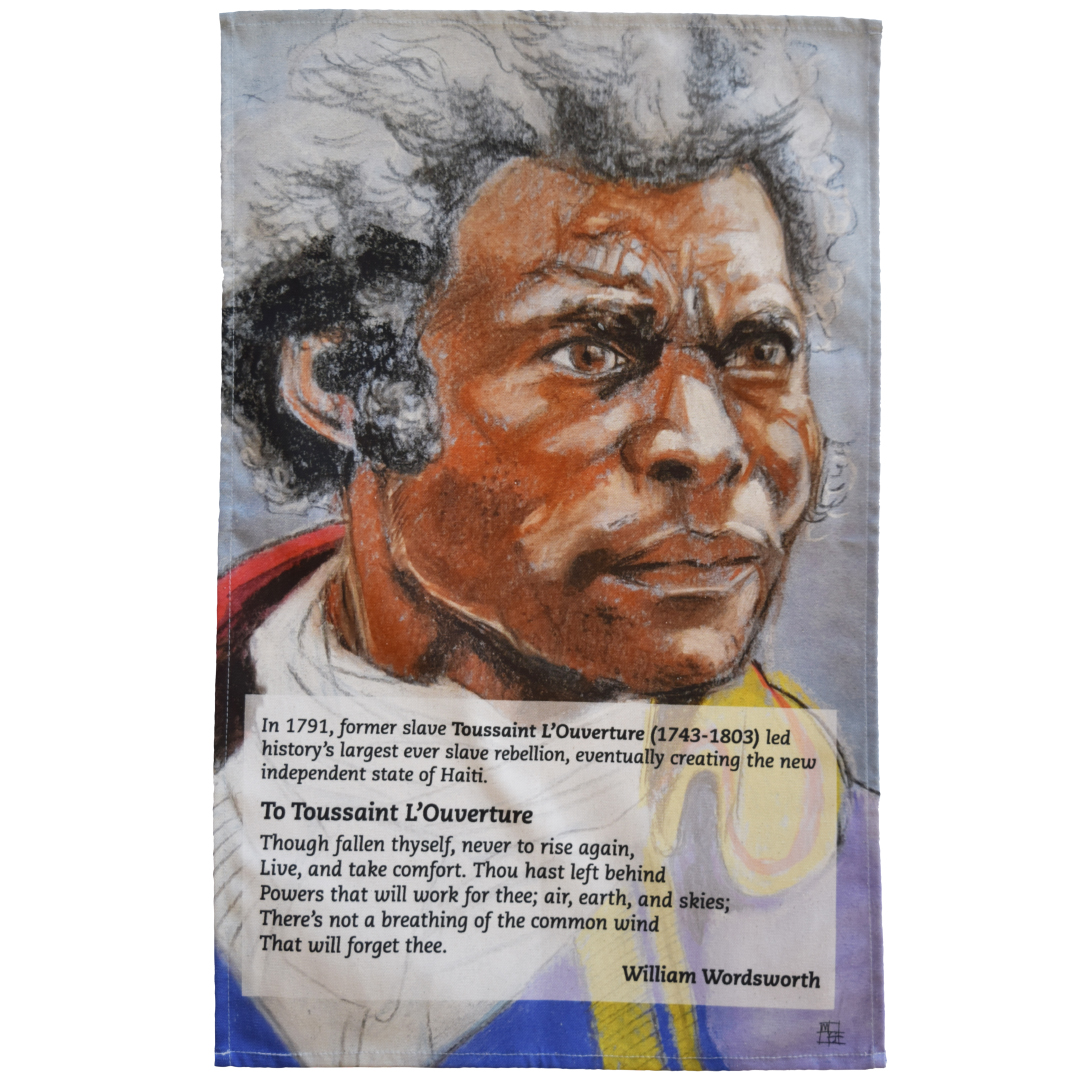

The Story of Toussaint L'Ouverture and the Haitian Revolution

The revolutionary leader who liberated his people and took on Napoleon's army...

Though fallen thyself, never to rise again,

Live, and take comfort! Thou hast left behind

Powers that will work for thee – air, earth, and skies –

There’s not a breathing of the common wind

That will forget thee!

William Wordsworth wrote these lines in 1802 upon hearing the news that Toussaint L’Ouverture was dying in a French prison cell.

Wordsworth, an abolitionist friend of

Thomas Clarkson, saw Toussaint as an ally in the struggle.

But where the English contested slavery by legal reform, Toussaint L’Ouverture had fought slavery more directly: by armed revolution.

Led by Toussaint L'Ouverture, the Haitian Revolution was the largest slave rebellion in history

Click to view our Toussaint L'Ouverture tea towel

Many of the leaders of the ‘Age of Revolutions’ (c. 1760-1840) were members of the ruling class. George Washington was a slave-owning land speculator, and the Marquis de Lafayette was, well, a Marquis…

But L’Ouverture, originally known as Toussaint Bréda, was born into slavery on one of the most brutal slave islands in the Caribbean: Saint-Domingue.

The wealthiest of France’s colonies, Saint-Domingue was the biggest sugar producer in the Americas.

But that sugar was produced by the enslaved labour of hundreds of thousands of kidnapped Africans.

This regime was maintained by a gruesome and legalised system of mass torture and death. It was the bloody jewel of European empire in the eighteenth-century Caribbean.

What’s more, it appeared quite stable. Relative to other sugar islands like British Jamaica, there was little slave insurrection on Saint-Domingue.

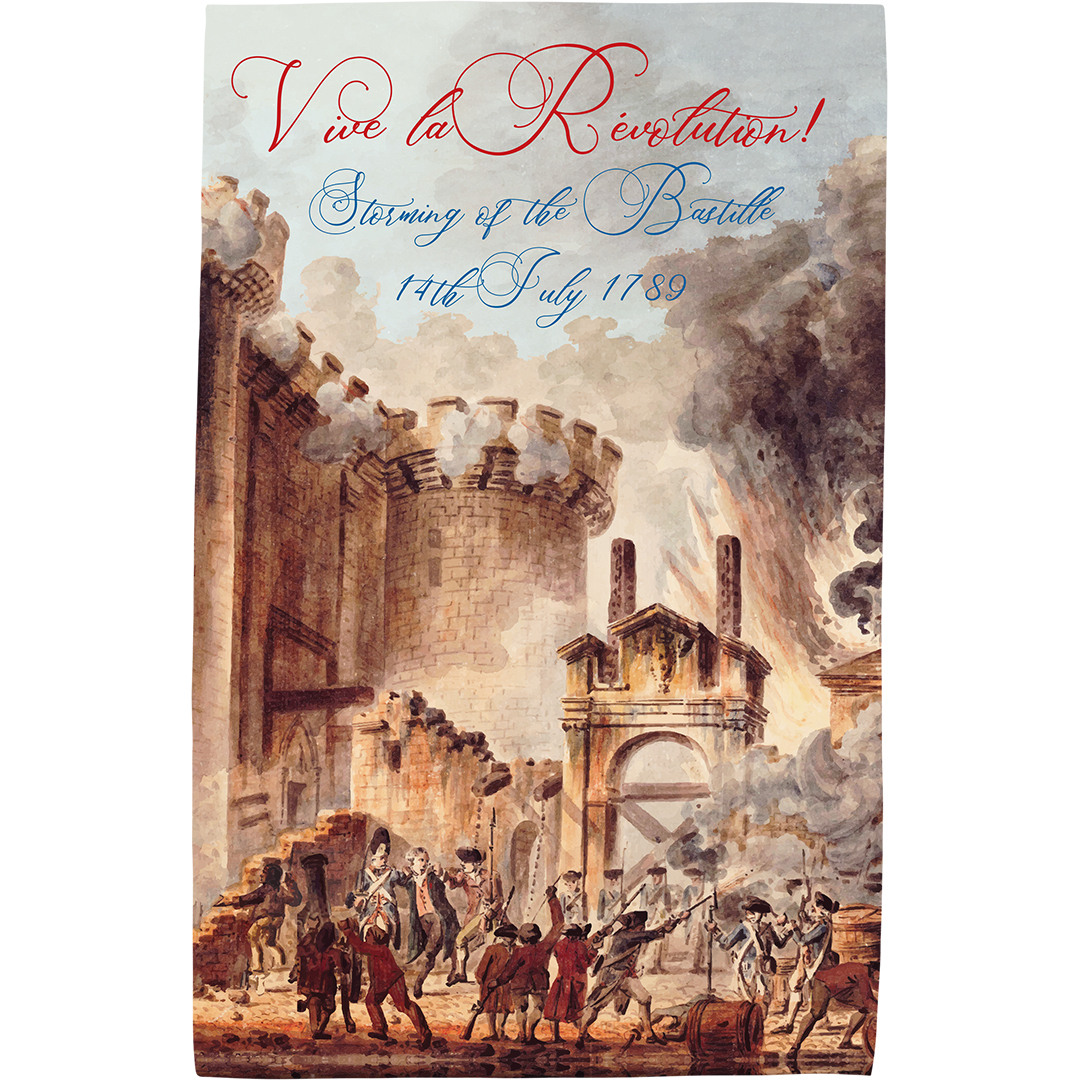

But then came 1789: the year of the

French Revolution.

The Storming of the Bastille in July 1789 is often seen as the moment that the French Revolution got properly underway

Click to view our Storming of the Bastille tea towel

Long considered a purely European affair, the struggle for a French Republic in the 1790s was anything but.

As the Old Regime of Bourbon absolutism began falling apart, the new French values of liberty, equality, and fraternity were discussed and promoted in the French-ruled Caribbean, too.

Then, amid ideological ferment and political instability, a massive slave insurrection was launched by the people of Saint-Domingue in August 1791.

And Toussaint quickly emerged as a leader of the movement.

But things were pretty complicated. In fact, Toussaint and the slave rebels were actually fighting against the republican cause, at least at first.

Many local supporters of the French Revolution in Saint-Domingue were racist supporters of slavery, so many slave rebels fought in the name of the King of France – hardly an icon of radicalism and liberty.

From 1792 to 1794, Toussaint actually served in the

Spanish Royal Army against revolutionary France.

But things change fast in times of revolution.

In August 1793, a radical French republican called Léger-Félicité Sonthonax arrived in Saint-Domingue and unilaterally declared the total abolition of slavery.

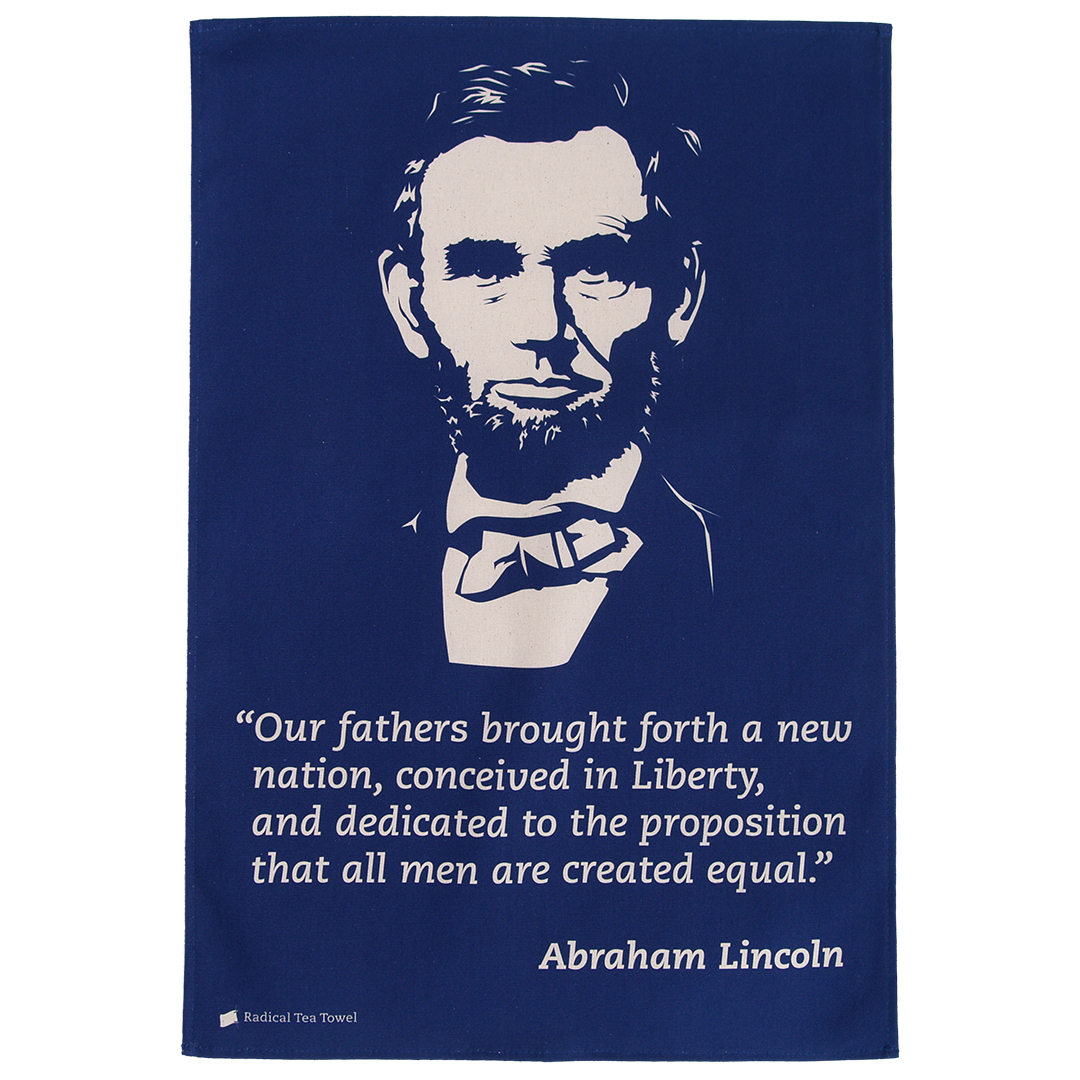

Seventy years before

Abraham Lincoln, this was the first emancipation proclamation in the Atlantic World.

Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, legally freeing 3.5 million enslaved African Americans

Click to view our Abraham Lincoln tea towel

In 1794, Paris ratified Sonthonax’s move – slavery was abolished throughout the French Empire.

The French republic was now decidedly anti-slavery. This was Toussaint’s cue.

By now a proven military commander, he defected from the Spanish and declared himself and his troops loyal to the French Revolution. He would remain so until his death.

L’Ouverture spent the rest of the 1790s defending the abolition of slavery against all comers: French Royalists, Spanish armies, a major British invasion which hoped to seize and re-enslave Saint-Domingue.

Toussaint beat them all. But they kept coming.

Napoleon Bonaparte – who seized power in France in 1799 – was the opposite of a Sonthonax. Deeply racist and eager for the restoration of slavery, he mobilised the largest imperial army ever sent to the Caribbean.

Toussaint even managed to hold that off until he was betrayed by his own commanders.

Shipped to France for imprisonment without adequate medical care, the ‘Black Spartacus’ of Saint-Domingue died in Fort-de-Joux prison on this day, the 7th of April, 1803.

But his cause was victorious, and Napoleon’s an abject failure.

Despite the death of their leader, Toussaint’s black comrades regrouped and destroyed the French invasion force.

Wordsworth was right: Toussaint’s legacy did live on.

On the 1st of January, 1804, they declared independence – not as Saint-Domingue, but as Haiti. It was the first and only successful slave revolution in history.