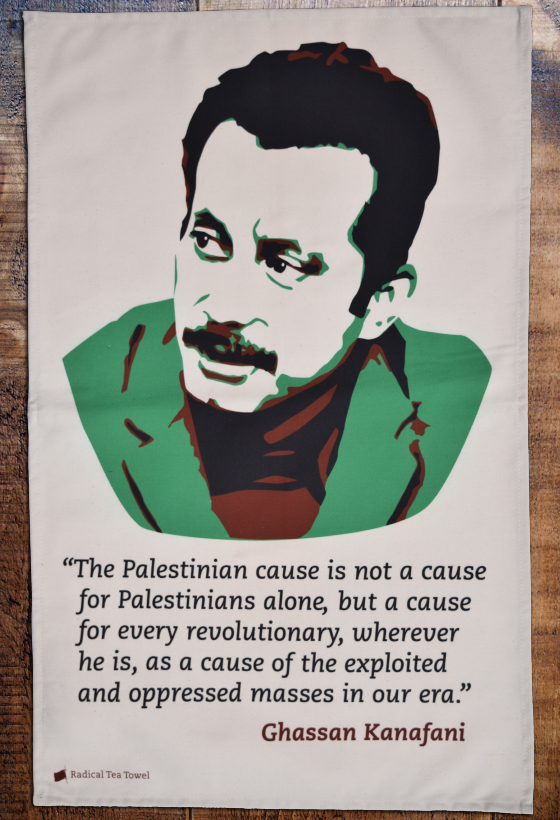

Ghassan Kanafani: The Commando Who Never Fired a Gun

Posted by Pete on 8th Jul 2018

It was a warm Egyptian summer when in 1975, a 39-year-old Palestinian writer, Ghassan Kanafani, strolled up to the Cairo HQ of the Afro-Asian Writers' Association.

The assassination of Ghassan Kanafani

This was a proud moment for the Palestinian. Along with Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, Kanafani - who'd grown up in a refugee camp in Syria - was receiving the Association's prestigious Lotus Prize for Literature.

The award celebrated Kanafani's dazzling achievements as an icon of postcolonial culture.

Or at least, this is what should have happened.

But Ghassan Kanafani received his prize posthumously. Forty-six years ago today he was murdered.

On the morning of 8th July 1972, Kanafani got into his Austin 1100 in Beirut. He was taking his seventeen-year-old niece, Lamees Najim, into town on a shopping trip.

When Ghassan turned the ignition, it detonated a bomb planted behind the bumper of the car. Both he and Lamees were incinerated instantly. Soon after, Mossad - the Israeli secret service - claimed responsibility.

The story behind this assassination goes right back to Kanafani's childhood.

Life as a refugee

At the age of 12, he was forced out of his home in the Palestinian coastal town of Acre by Israeli troops. His family fled first to Lebanon and then to Damascus, where for many years they would struggle to make ends meet in a UN refugee camp.

This was Kanafani's personal part of the collective Palestinian experience known as the 'Nakba' (Catastrophe) where, in 1947-8, the armed forces of what would become the Israeli state drove more than 700,000 Arab Palestinians from homes they had lived in for centuries.

The Jewish-Israeli historian, Ilan Pappé, has called this the 'ethnic cleansing of Palestine'.

The Nakba left a profound mark on the young Kanafani. A refugee has to live in poorly-funded camps, travel long-distances for work, and is rarely welcomed by host populations. The Palestinian refugee has to do all this within sight of the homeland they're prevented from returning to by Israeli guns and barbed wire.

These difficulties and torments came through in Kanafani's written work. Virtually all of his writing focused on the modern Palestinian experience.

The short story 'Men in the Sun' (1962) for example, explored the challenge of articulating Palestine's cause to the world, while 'Returning to Haifa' (1970) - Kanafani's masterpiece - confronted questions of resistance and the true nature of anti-colonial liberation.

In politics as in literature, the Palestinian struggle was at the foreground of Kanafani's life. From 1967, he was a spokesman of the 'Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine' (PFLP), a Marxist group which sought the same type of international socialism which Che Guevara was advancing in South America.

It was Kanafani's association with the PFLP which ultimately led Mossad to murder him in July 1972.

Murdered for his words

The assassination was a reprisal for the Lod Airport Massacre. In May 1972, members of the 'Japanese Red Army' supposedly affiliated with the PFLP had murdered 26 people - mostly Puerto Rican pilgrims - at an Israeli air terminal.

There is, however, considerable evidence that this was a rogue operation not approved by the PFLP high command. It went against the group's established rejection of violence against civilians and the one Palestinian involved in its planning, Wadie Haddad, was expelled from the group soon after.

Whether it was rogue or not, Kanafani wasn't involved in the political decisions of the PFLP. He was concerned with public information and propaganda, only ever hearing about operations after-the-fact.

Whatever responsibility the PFLP may have borne for Lod, therefore, Kanafani carried none of it - certainly not enough to justify his murder by the Israeli state (if anything could justify such barbarity).

The (cruel) likelihood is that Mossad simply used Lod as an excuse to silence an eloquent, persuasive, and popular voice for the cause of Palestinian liberation.

As for Kanafani's seventeen-year-old niece, Lamees Najim, she was a child whose death Israel's government deemed justifiable to preserve its (now 70-year-old) occupation of Palestine.

But that occupation, for all its military might, was clearly not invincible.

Kanafani wouldn't have been murdered if his hard-hitting critiques of the Israeli state didn't pose a threat. Tel Aviv feared a man whose writing could change opinion in favour of the Palestinians.

"He was a commando who never fired a gun, whose weapon was a ball-point pen, and his arena the newspaper pages", wrote one of Kanafani's obituaries. He is perhaps one of the great twentieth-century examples of the pen frightening the sword.

As another Arab writer, Ahmed Shawqi, once wrote: "The revolution of minds removes mountains."