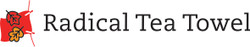

Another England: The Story of the Wat Tyler and the Peasants' Revolt

Posted by Pete on 14th Jun 2020

Wat Tyler, leader of the Peasants' Revolt, was murdered by the Crown today, 15th June, in 1381. His death is the founding sacrifice in the radical history of England.

Today in 1381, a lion was killed by snakes.

The snakes wore fine clothes – one of them even had a crown.

The lion was Wat Tyler, the Kentish worker who led the Peasants’ Revolt.

In May 1381, England had risen up against the government of King Richard II.

To fund his bloody wars in France, Richard had resorted to a series of poll taxes – charging everyone in England the same amount, regardless of whether they were a wealthy lord or an impoverished farmer.

In November of 1380, the third of these poll taxes in as many years was announced.

For the working people of England – the toilers on whose labour Richard’s majesty was built – this was the last straw.

Fed up with exploitation by a government which despised them, peasants and artisans across England rebelled.

The rebels were most numerous in the south and east, with Kent producing the most militant.

These Kentish warriors were led by Wat Tyler, a man of obscure origins (recording the lives of 'lesser' folk wasn’t a habit of medieval England).

On 10 th June 1381, Tyler marched his troops into Canterbury where they deposed the Archbishop and raided the properties of other notables associated with Richard II’s hated royal council.

The Kentish rebels then set out for London, linking up with their comrades from Essex, Suffolk, and Norfolk at Blackheath (just south of the capital) on the 12 th.

Here they heard from the radical cleric, John Ball (whom Wat Tyler’s men had broken out of prison in Maidstone).

Ball, whose speech echoes down the centuries, asked the gathered rebels:

Ball’s radical egalitarianism meant one thing – this was no longer a revolt, it was a revolution.

The peasants’ cause had outgrown the issue of a single tax to challenge the whole hierarchy of medieval England and the oppressive institution of serfdom at its core.

From Blackheath, Tyler led the peasant army on to London itself.

On the 13th, they crossed London Bridge and set to ransacking the royal prisons, Fleet Street, and the Savoy Palace.

A force led by a woman called Johanna Ferrour even raided the Tower of London.

With his armies in France, King Richard was compelled to negotiate.

Hoping to appease the rebels for long enough to raise an army to crush them, the King pledged to abolish serfdom and punish those of his officials who had abused the people.

Wat Tyler saw through the lie and refused to withdraw from London without more concrete assurances.

Richard agreed to meet Tyler at Smithfield, near the site of Farringdon tube station in East London.

This was where William Wallace had been executed in 1305, and it was about to witness yet another crime by the English Crown.

Mid-negotiation, the King’s escort attacked and murdered Wat Tyler.

After this royal treachery, the Kentish rebels were run out of London. In the weeks and months that followed, royal forces repressed the peasant revolutionaries across England, from York to Norwich.

But in the long term, Wat Tyler triumphed.

Now painfully aware of how revolutionary the English peasantry could be, the Crown abandoned its poll tax scheme, and serfdom in England soon began to wither away.

Wat Tyler is the original hero of English radicalism.

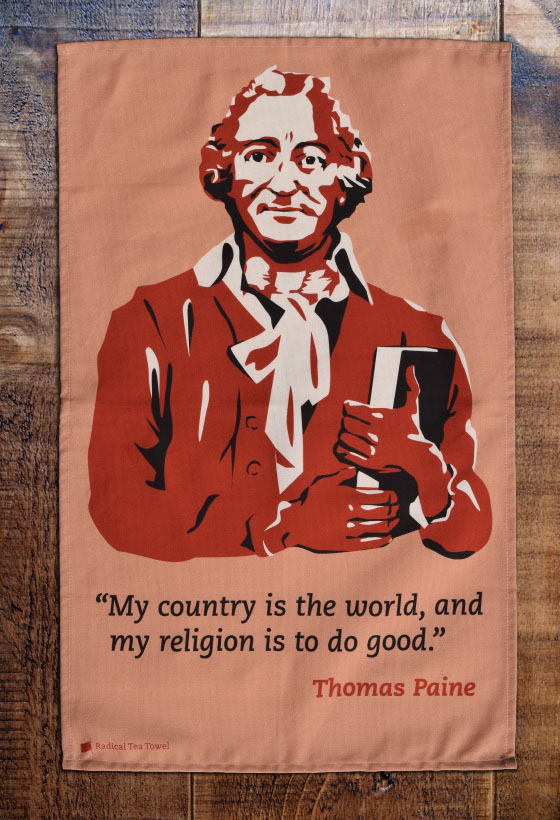

He was an inspiration to Tom Paine and William Morris, and his revolution against Richard II was a model for the resistance to Margaret Thatcher’s poll tax plan in 1990!

What’s more, Wat Tyler reveals a version of England we’re rarely taught.

Not the England of kings and colonialists, cherished by the Right and justly condemned by progressives, but the England of ordinary, magnificent people who, when pushed too far, have risen up against oppression.

This is the England of the Diggers, the Chartists, the Abolitionists and the Bristol Bus Boycott, and it’s our honour at Radical Tea Towel to keep its memory alive.