We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the e-Privacy rules, we need to ask for your consent to use non-essential cookies (such as analytics and marketing). You can allow or decline these cookies. Essential cookies (for things like basket and checkout) will always be used. For more details, please see our Privacy Policy.

The London Dock Strike of 1889

The strike that led to a sea change in the British labour movement...

“The people’s flag is deepest red,

It shrouded oft our martyred dead

And ere their limbs grew stiff and cold,

Their hearts’ blood dyed its every fold.

So raise the scarlet standard high,

Beneath its shade we’ll live and die,

Though cowards flinch and traitors sneer,

We’ll keep the red flag flying here.”

It’s probably the most famous socialist anthem ever, sung at rallies and protests the world over.

But what many people don't know is that Jim Connell, the Irish nationalist and socialist, was inspired to write it by the London Dock Strike of 1889…

Our London Dock Strike tea towel is based on a contemporary poster requesting financial support from sympathetic members of the public

Click to view our London Dock Strike tea towel

The British Empire was at the height of its power in the 1880s. London was the commercial capital of the world and its docklands were booming.

But a fat lot of good that did the tens of thousands of dock workers in the city.

They were overworked and paid barely anything. Many of them were Irish immigrants, so were subject to racist abuse, too.

It was high time to fight back.

The strike began in the West India Docks. Wealthy dock owners decided to cut the bonus which the workers received for unloading a ship ahead of time, known as ‘plus money.’

So, when the dockers did a great job emptying the Lady Armstrong in mid-August 1889, they clashed with management.

The strike began on 14 August and went on for five weeks. It grew quickly, and soon became one of the major industrial disputes in 19th century British history.

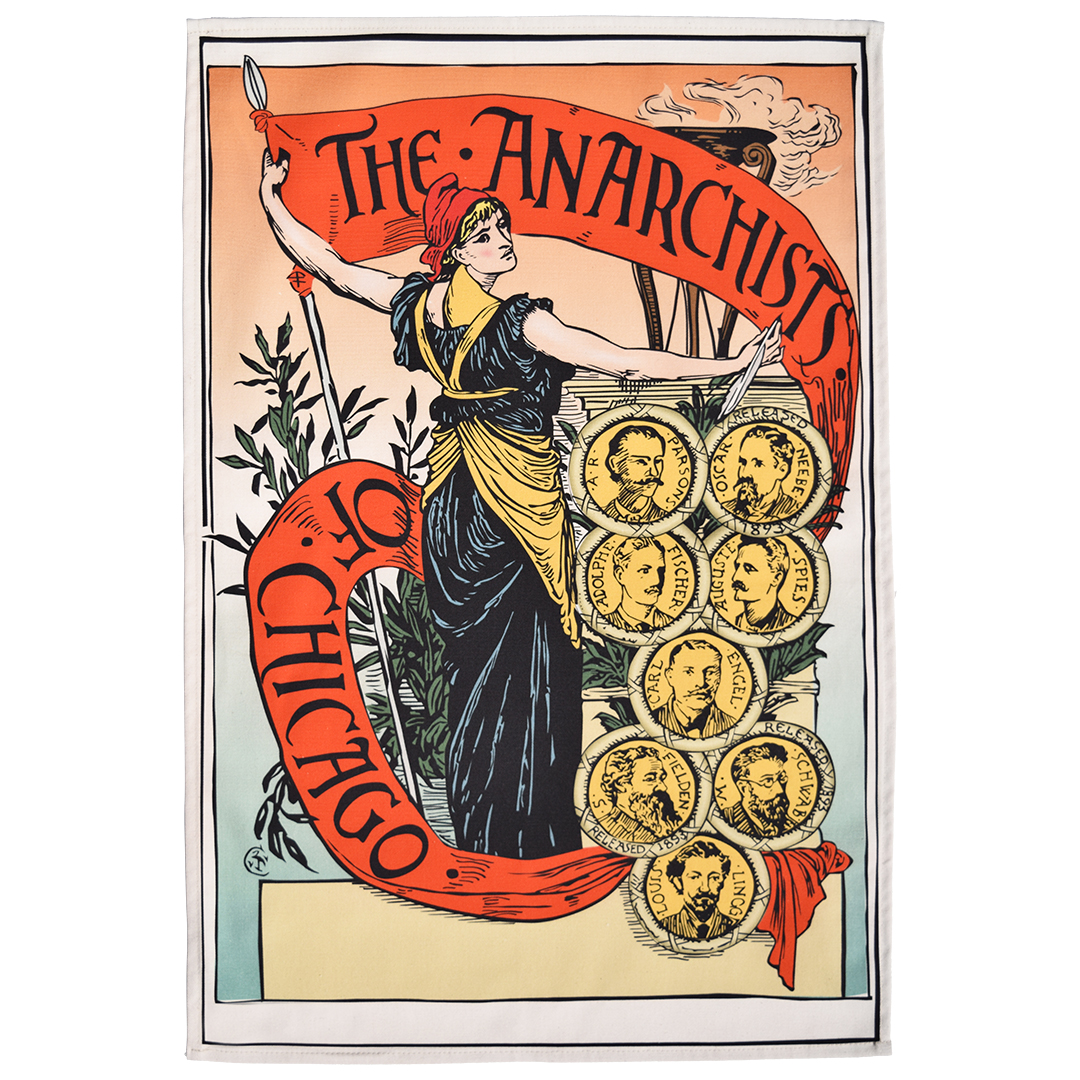

The 1880s was a time of radical change across the West, with the Haymarket Affair becoming a cause célèbre in radical circles

Click to view our Anarchists of Chicago tea towel

Soon, 100,000 workers were on strike, spread across the entire Port of London.

And as their numbers grew, so too did their demands. Rather than just plus money, the dockers were now demanding an increase in basic pay and improved working conditions.

They wanted the ‘docker’s tanner’ – that is, a rate of sixpence per hour. And they wanted shift times limited to 4 hours.

The strike was an amazing show of multinational, working-class power. Not only were many of the strikers immigrants, but when strike funds ran low, £30,000 came in from trade unions all across Australia to keep them going.

The Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Labourers’ Union, which had been tiny before the strike, gained tens of thousands of new members as the struggle went on.

This was a watershed for organised labour in Britain.

Before the 1880s, only craft sectors had a strong trade union presence. So-called ‘unskilled’ workers, like dockers, were often left without organisation.

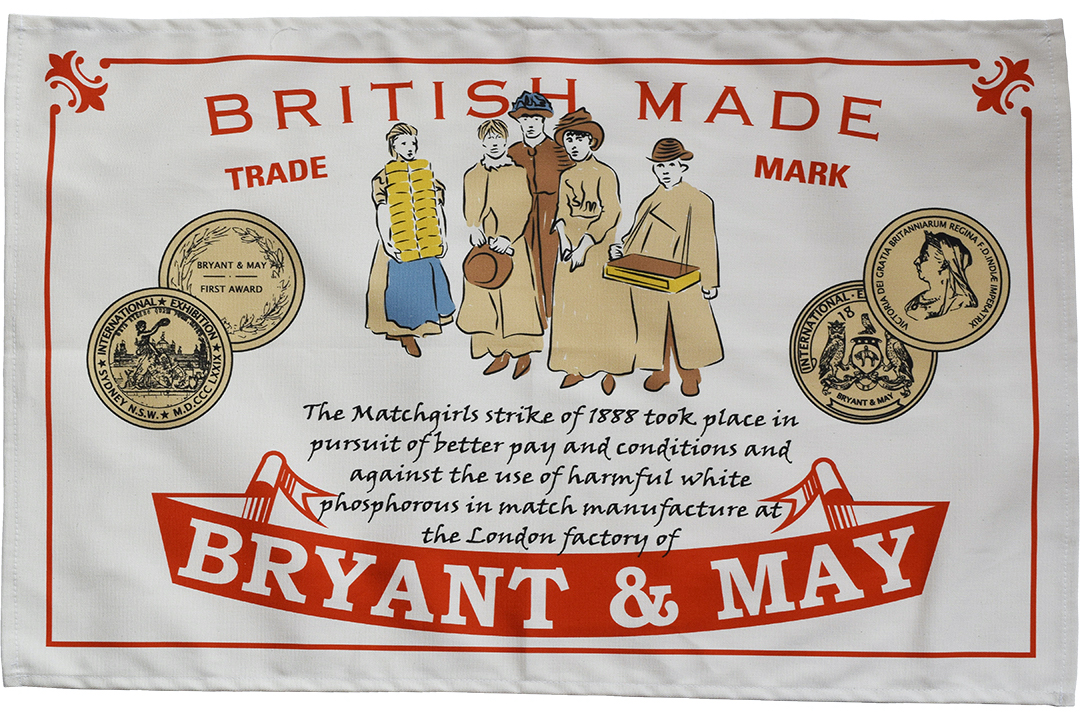

This began to change with the Matchgirls' Strike of 1888, not far from the docklands in the East End of London.

Just a year earlier, the Matchgirls at Bryant & May factory went on strike for better pay and conditions

Click to view our Matchgirls' Strike tea towel

But the explosion of the Dockers’ Union in 1889 put trade unions on the map, and millions of workers across Britain joined their own unions and started to organise.

It almost didn’t matter whether the dockers won the actual dispute. But win it they did.

On 15 September 1889, the dock bosses capitulated. The workers got their docker’s tanner and reduced hours.

There’d be no going back now. A new, radical force had been created in British politics: the London dockers.

And they sure as hell kept the red flag flying in years to come.

From their part in the 1926 General Strike to their support for the anti-fascists at Cable Street, they would be the tip of the spear for the British Left for decades to come.

That’s how a strike changes the world, that’s the power of organised labour!