The Native American Suffragist: Mary Bottineau

Posted by Pete on 14th Dec 2024

The movement for women’s suffrage in the U.S. was diverse.

Although the leadership was dominated by white women like Susan B. Anthony and Alice Paul, feminist activism came from all across American society.

Mary Louise Bottineau Baldwin c. 1910-15

Despite racial discrimination within the movement, black women such as Ida B. Wells were key.

And the same was true of indigenous women, too.

Native Americans including the Yankton Sioux activist, Zitkala-Sa, shared in the struggle for women’s right to vote.

And so did Mary Louise Bottineau Baldwin, of the Métis Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, born on this day in 1863.

Non-white women such as Ida B. Wells and Mary Bottineau were key in the movement for women's suffrage in the US

See the Ida B. Wells tea towel

Bottineau was born on Ojibwe (Chippewa) land which was later made part of North Dakota. Her family was mixed indigenous and French-Canadian.

Mary’s dad, Jean, was an activist lawyer, working on behalf of the Ojibwe through the U.S. legal system.

In 1867, the family moved to Minnesota, where Mary went to school.

Mary shared her dad’s radical politics, and they moved to Washington D.C. together in the 1890s, to defend Ojibwe land claims before the Federal government.

Mary’s preference was to fight for indigenous rights and freedom within the U.S. legal system, although other Native Americans continued to struggle against the U.S. state itself, as an occupying power.

In 1904, Mary accepted a role as a clerk in the Federal Office of Indian Affairs (OIA). Remarkably, she was just one of two actual Native Americans working in the bureau.

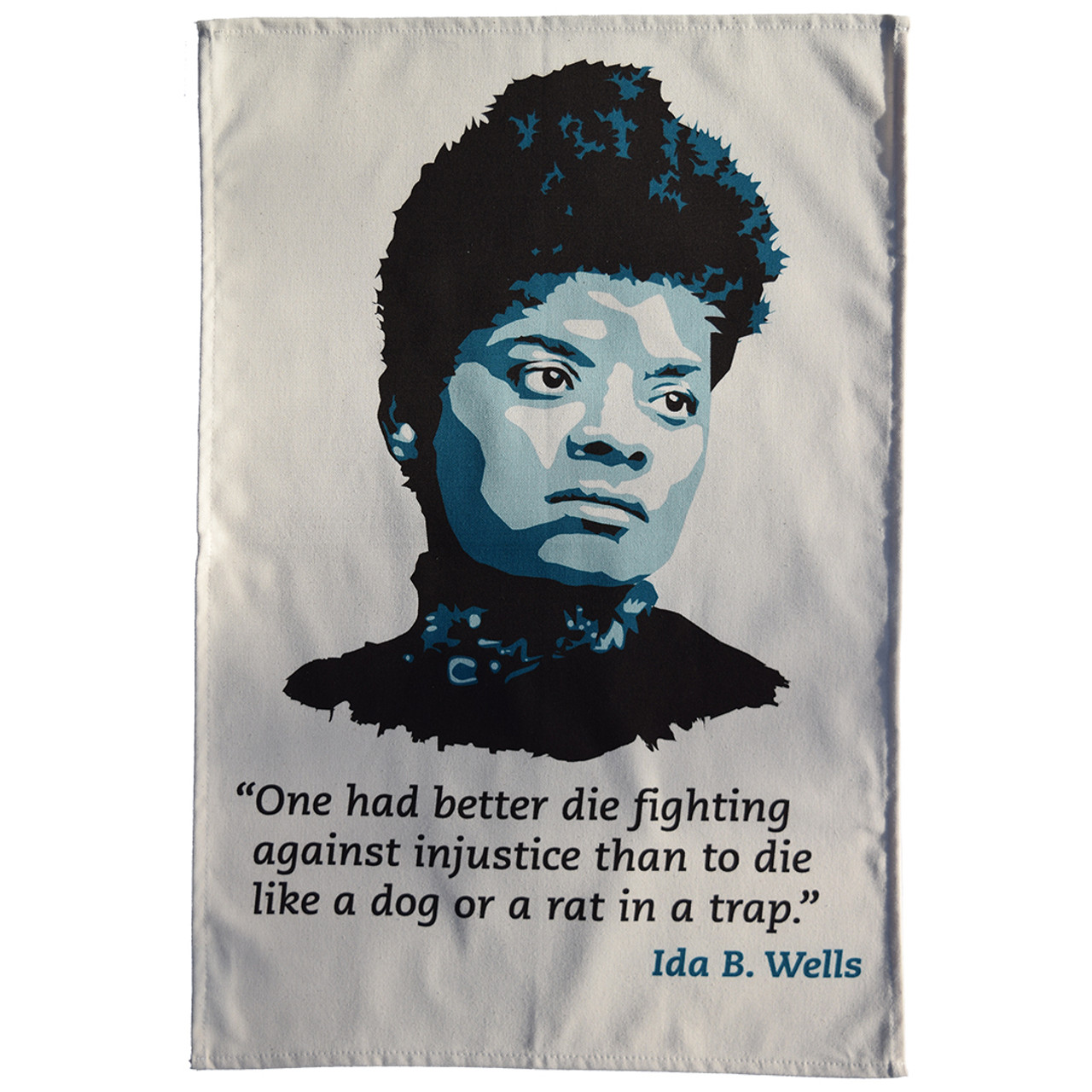

See the Canada First Nations tea towel

In parallel with her government work, Bottineau joined the Society of American Indians (SAI) after it was created by indigenous activists in 1911.

The organisation pushed for Native American rights and the promotion of indigenous culture in the U.S.

"The trouble in this Indian question which I meet again and again is that it is not the Indian who needs to be educated so constantly up to the white man, but that the white man needs to be educated to the Indian."

In 1914, Bottineau was part of an SAI delegation to the White House that demanded an end to the colonial ‘wardship’ status of indigenous peoples in the United States, under which they were treated as legal dependents.

Bottineau fell out with the SAI leadership in 1919, especially over her connections to the U.S. government, but she continued to agitate for indigenous causes regardless.

In 1912, Bottineau had enrolled in the Washington College of Law to gain more expertise for her activism.

Two years later, she became the first ever Native American and woman of colour to graduate from the school.

Bottineau’s time in D.C. during the 1910s also put her in contact with the political activism of the women’s suffrage movement.

Bottineau saw in women’s suffrage another liberation struggle to support.

She saw connections, too, between democracy for women in North America and indigenous freedom.

Bottineau pointed out that many precolonial Native American societies recognised far more gender equality than European ones did:

"Did you ever know that the Indian women were among the first suffragists…?"

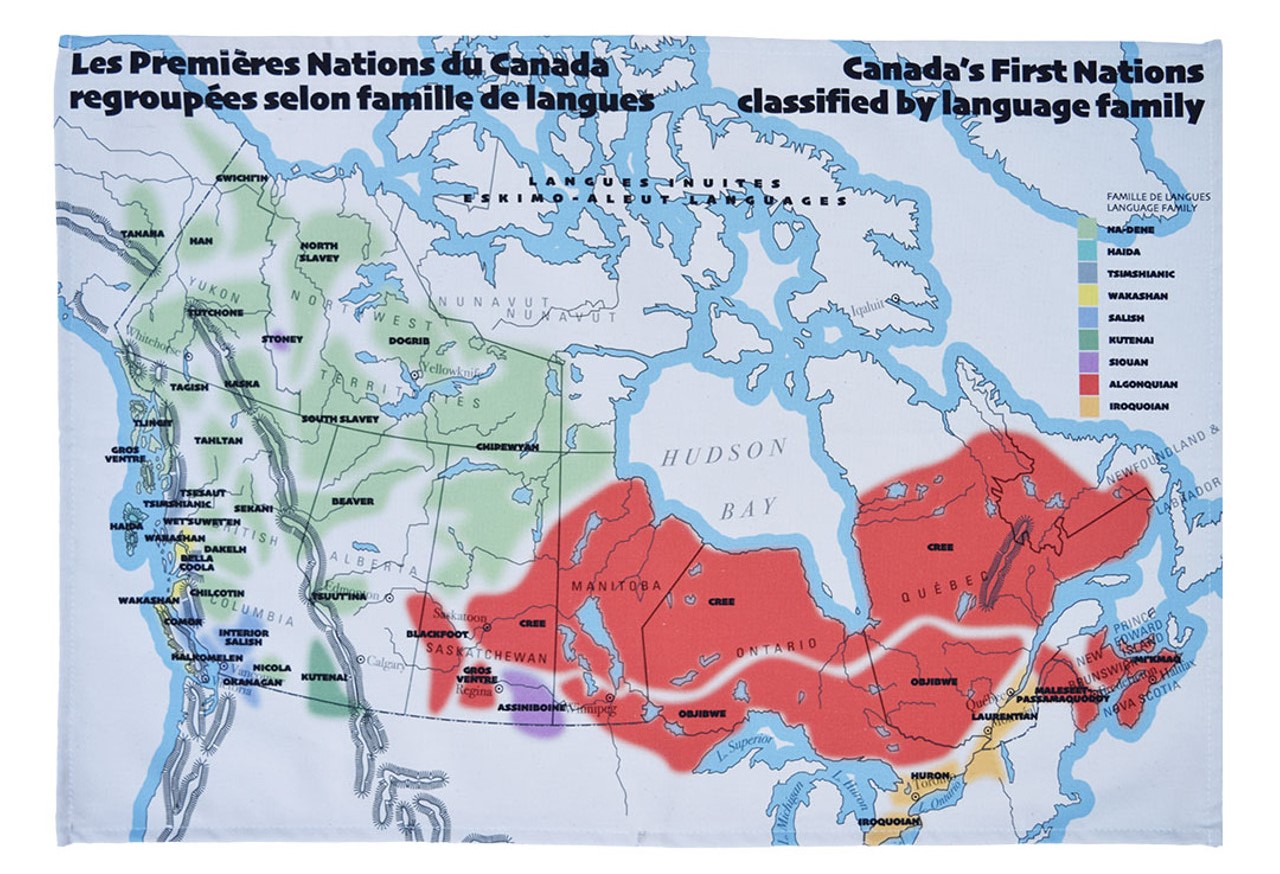

In 1913, Bottineau took part in the Women’s March on Washington for the right to vote. And, like Ida B. Wells, she faced down racial discrimination to do so.

Whereas there had been efforts by white organisers to either exclude or segregate black participants, Mary Bottineau was encouraged to take part in ‘traditional Native dress,’ as imagined and stereotyped by Europeans.

Mary Bottineau took part in the 1913 Washington DC Suffrage Procession - on her own terms

See the Washington DC Suffrage Procession tea towel

Bottineau refused – there was such a thing as indigenous modernity, too – and instead took part as a fellow citizen demanding modern democratic rights on behalf of women and indigenous women, in particular.

As Bottineau pointed out to white activists who thought of her as ‘exotic’ because of her race:

"The practical problems of life that the Indian woman meets are essentially identical with those the white woman confronts, and their treatment should be identical."

Mary Bottineau presents another model in the diverse past and present of indigenous activism in North America: combining legal protest with government work, and indigenous cultural autonomy with anti-racist feminism.

Although different in her tactics, she is part of the same indigenous radical history as the anticolonial struggles of Tecumseh and Crazy Horse, and of the American Indian Movement of the 1960s and 1970s: a centuries-long struggle for real freedom in North America.