We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

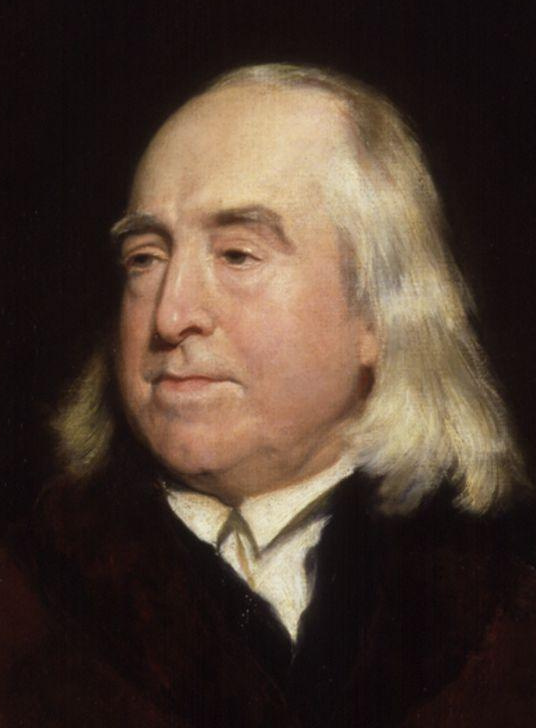

The Radical Philosophy of Jeremy Bentham

Born on the 15th of February, 1748, Jeremy Bentham sought to reform the institutions at the heart of British society

“The greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation.”

Jeremy Bentham was born in February, 1748.

And on this day in 2023, his mummy-like “auto-icon” is still on display in a glass cabinet in the foyer of University College London, seated at Bentham’s old desk chair…

He figured that keeping his remains on like this, after his death in 1832, would be more useful than burial. His intellectual disciples might sit with his body to discuss and debate the big ideas of the day.

![]()

Bentham and his ideas helped to inspire the founders of London University, now University College London

Jeremy Bentham was a peculiar man, in more ways than one - the auto-icon being a case in point.

But he was also peculiarly

radical.

In the political debates of Britain and the wider world towards the end of the eighteenth century, Bentham was a frequent dissenter.

It hadn’t always been that way. Bentham was born into a very wealthy family in London. Fiercely intelligent, he was trained as a barrister.

Some of his early work in the 1770s included writing propaganda for the British government, to denounce the

revolutionaries in North America.

But as the 1780s and 1790s went on, Bentham grew increasingly frustrated by the aristocratic establishment running Britain.

Bentham lived through an age of revolutions, from the American War of Independence to the French Revolution of 1789

Click to view our Storming of the Bastille tea towel

He was busy developing a philosophy – “utilitarianism” – which lent itself to the radical reform of traditional institutions.

It was based on the idea that actions and policies were good or bad insofar as they led to, or didn’t lead to, the “greatest happiness of the greatest number.”

Against this standard, swathes of British social practice – prisons, gender inequality, colonialism – appeared indefensible to Bentham.

So, he began to demand reform.

Bentham supported women’s suffrage, as would his disciple

John Stuart Mill.

Bentham even backed the decriminalisation of homosexuality in an unpublished essay in 1785. It was the first known argument for the reform of homophobic legislation in English history.

Bentham's liberal approach to sexuality was censored by Victorian editors and overlooked until well into the 20th century

Click to view our LGBTQ+ tea towel

Like Rousseau earlier in the eighteenth century, Bentham also explored a defence of animal rights.

And, in 1789, he produced a “Plan For An Universal and Perpetual Peace”, which called on Britain and France to demilitarise themselves and set free their overseas colonies.

Bentham’s reformist arguments didn’t get far in late eighteenth-century England, especially once the government took a sharp

reactionary turn in response to the French Revolution.

As the opening for reform narrowed at home, Bentham looked to the possibility of revolution abroad.

He was initially supportive of the

French Revolution, and a pen pal of Mirabeau. In fact, Bentham was made a citizen of the French Republic in 1792. And he used this new status to urge France to emancipate its colonies in the Caribbean.

Twenty years later, Bentham became an enthusiastic champion of the

Spanish American Wars of Independence.

He wrote to revolutionary leaders in Spanish America, proposing legal reforms they ought to make, and even considered moving to Venezuela to get right in the middle of this new theatre of change.

But by this point, Bentham was an old man. With the plans for his auto-icon prepared in his will, he died in 1832.

For decades, he had been one of the most radical philosophers in Britain, at a time when dissent was neither convenient nor risk-free.

That's why, on his birthday, we're celebrating Jeremy Bentham - a radical philosopher, and a philosophical radical.