Big Ideas and Blind Spots: The Life of John Stuart Mill

Posted by Pete on 20th May 2021

What can Mill's flawed vision of freedom teach us about the radical struggle?

Born today in 1806, John Stuart Mill didn’t have a normal English childhood…

He was speaking Ancient Greek at three years-old and Latin by the age of eight. By ten, he was reading Plato and Demosthenes with ease, as well as reading up on the natural sciences in his spare time.

This peculiar regimen was the work of his father, the utilitarian philosopher, James Mill (1773-1836).

One of the most famous British political thinkers of the day, James passed for a radical in the repressive context of early-19th century England, advocating for certain democratic reforms.

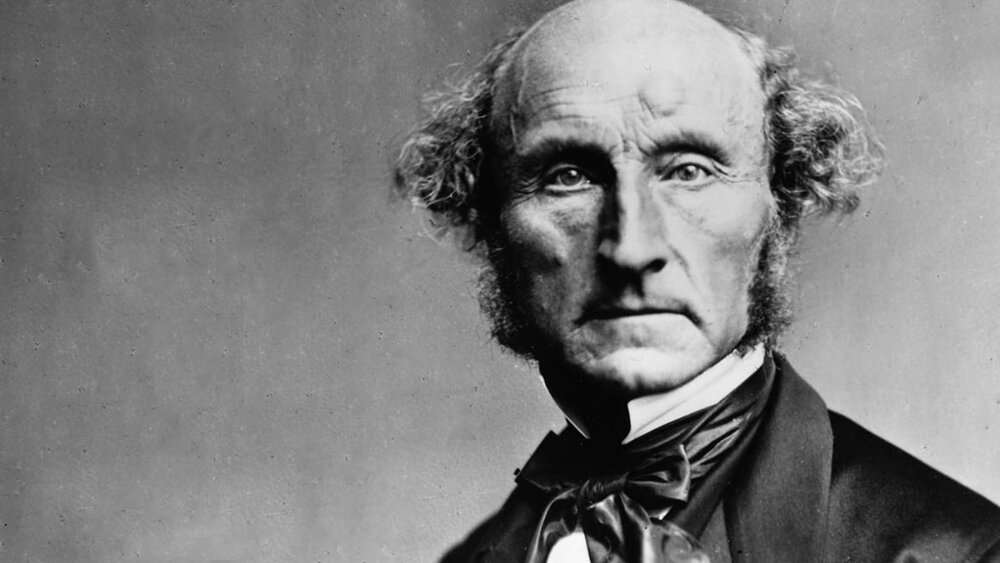

Known for his peculiar haircut, Mill was among the most famous philosophers of his day.

Working with the altogether more impressive Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), James Mill headed up Utilitarianism, a brand of late-18th century liberal philosophy committed to the “greatest happiness of the greatest number.”

So, when John Stuart was born, his father planned from the outset to build a genius out of him, through a rigorous program of home-schooling.

Whether because of this intense education, or some inner talent, John Stuart Mill grew into a thinker and radical far bolder and more impressive than his dad.

He couldn’t go to either of the Oxbridge universities because he wasn’t Anglican, so instead he went to University College London (founded by his godfather, Bentham).

After that, John Stuart followed his father into the British East India Company, where he worked on the governance of India for 35 years.

One of Mill's most famous and controversial arguments was the idea of the 'tyranny of the majority', captured here by the poet John Dryden back in 1681.

Click to view our People's Judgement tea towel

Along the way, he met, befriended, and eventually married the feminist philosopher, Harriet Taylor (1807-58).

Harriet had an immense intellectual impact on John Stuart’s thought about politics and economics, more so than anyone else.

As he wrote in memory of her in 1858:

"Were I but capable of interpreting to the world one half of the great thoughts and noble feelings which are buried in her grave, I should be the medium of a greater benefit to it, than is ever likely to arise from anything that I can write."

He then published On Liberty, his most famous essay, arguing for the principle that:

"The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection."

He was making the case, more comprehensively than ever, that individual freedom – not least freedom of expression – shouldn’t be infringed because it is unconventional or unpopular.

In the last years of his life, Mill’s arguments became even more radical.

Heavily influenced by Harriet, he published The Subjection of Women (1869) which, in the tradition of Mary Wollstonecraft, rejected the conventional belief that women were naturally inferior to men.

In doing so, John Stuart Mill became the first man at the forefront of British politics to reject the male-only franchise, soon to be followed by future Labour-leader Keir Hardie.

Mill's The Subjection of Women is often read in tandem with Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published 77 years earlier.

Click to view of Mary Wollstonecraft tea towel

But while he cut against the grain in many radical ways, there were certain, gaping holes in Mill’s vision of human freedom.

Namely, that what he called the “barbarian” world – in effect, all of Asia and Africa, at least – was not invited to partake of such freedoms.

As he made crystal clear at the start of On Liberty, Mill’s vision of a society where individuals were free to self-determine and flourish was not meant for these “barbaric” regions which were, I’m sure coincidentally, also governed by the British Empire which paid Mill’s salary…

Not until these societies had acquired a higher level of “civilisation” could they handle the liberties he was calling for in England.

At a moment when more and more thinkers in the British Isles – Richard Cobden, Karl Marx, Sylvia Pankhurst, James Connolly – were beginning to call out the British Empire for the oppressive abomination it was, John Stuart Mill contorted his vision of freedom to help justify it.

I suppose this is the cautionary tale of Mill’s work, which was so often courageously radical. Even those who consider themselves supporters of human freedom are not immune to blind-spots and racial prejudice.

So no matter how long the struggle is or how tough the fight, we must always remember that an injury to one is an injury to all. Or, in the words of Emma Lazarus, none of us are free until all of us are free.