We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the e-Privacy rules, we need to ask for your consent to use non-essential cookies (such as analytics and marketing). You can allow or decline these cookies. Essential cookies (for things like basket and checkout) will always be used. For more details, please see our Privacy Policy.

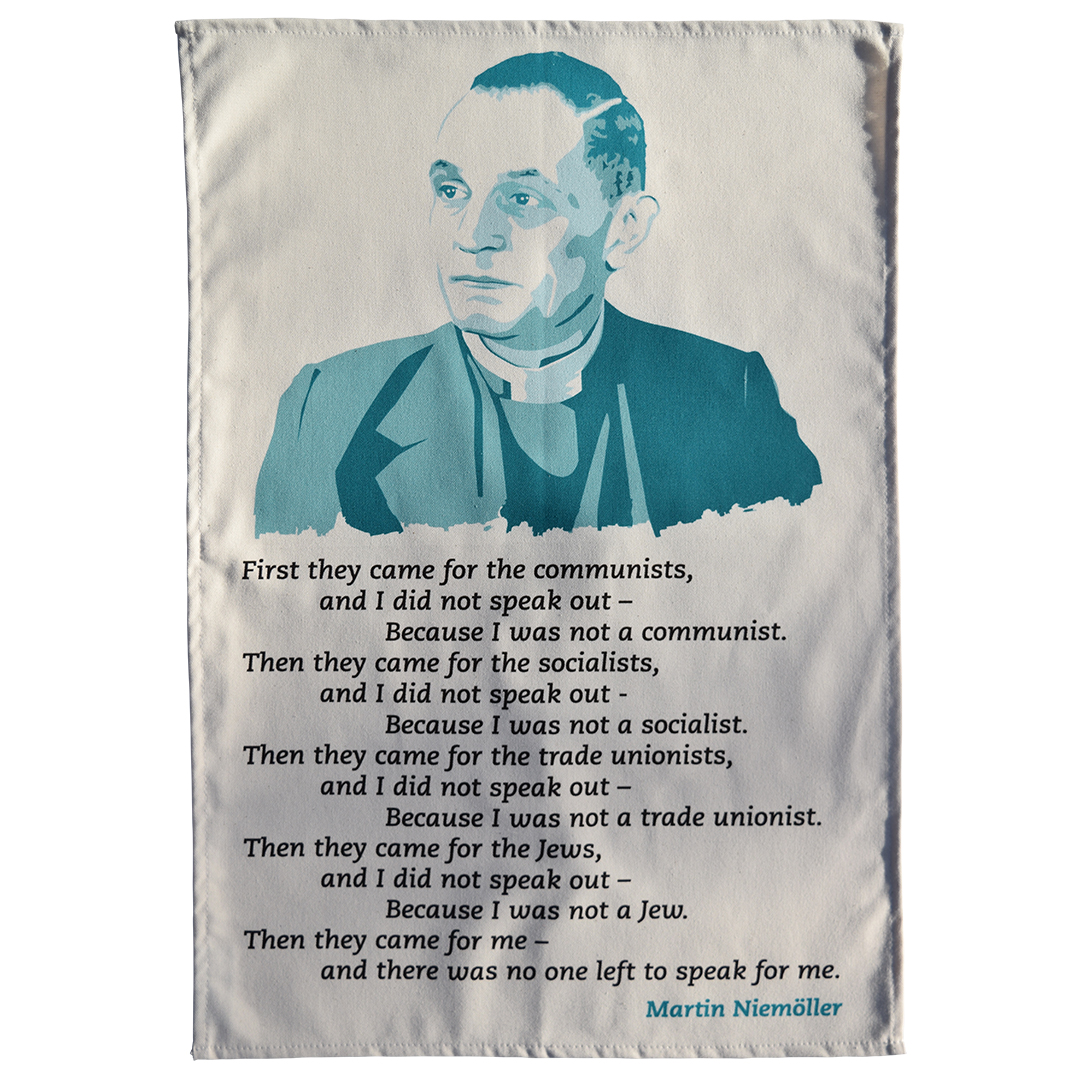

Then They Came for Me: The Story of Martin Niemöller

Martin Niemöller's confession is known across the world - but who actually was he?

As far as radical, progressive politics is concerned, Martin Niemöller was not a commendable man.

He was born into a conservative German family in 1892 – and in this case, the apple fell extremely close to the tree.

After school, Niemöller joined the Kriegsmarine – Kaiser Wilhelm’s navy – and he served in the Great War as a U-boat commander.

As the war came to an end in 1918, German socialists and communists led a revolution which overthrew the monarchy and established a republic.

Rebel sailors in the Navy were key to this popular victory, but Martin Niemöller couldn't have been more disapproving...

Niemöller is famous for his criticism of the Nazi regime - but the story is a little more complicated than you might think.

Click to view our Martin Niemöller tea towel

Revolted by the mass embrace of democracy, Niemöller quit the Navy to retrain as a Lutheran pastor.

Whilst working towards this new goal, he served as a commander in the reactionary Freikorps, a proto-fascist paramilitary army known for fighting and murdering German leftists – including

Rosa Luxemburg – in the years after the war.

With this background, it’s not at all surprising that Niemöller celebrated Hitler’s rise to power in 1933.

He had no problem with the Nazi persecution of Communists, Socialists and Jews.

It was only when the Nazis began to intrude on the autonomy of the Protestant churches in Germany that Niemöller spoke out.

The Marxist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg was killed by the Freikorps in January 1919.

Click to view our Rosa Luxemburg tea towel

In late 1933, Niemöller helped found the Pfarrernotbund against the ‘Aryan Paragraph’ – the requirement that the Protestant Christian churches expel all members of Jewish descent.

The next year, the Pfarrernotbund was reorganised as the Confessional Church, which united German Protestants committed to resist the Nazification of their faith.

But Niemöller’s form of disobedience to the Nazis, while personally dangerous, was always deeply limited.

He was primarily concerned with the independence and interest of the Protestant churches. As a political reactionary, he wasn’t speaking out against the mass arrests and murder of German leftists. His silence on this front speaks volumes.

And his ‘resistance’ – if it can be called that – to official anti-Semitism was limited to those of Jewish descent who had converted to Protestant Christianity.

At the same time as he was objecting to the Aryan Paragraph being forced on his church, Niemöller was giving anti-Semitic sermons, repeating the old Christian trope that the Jews should be punished for the crucifixion of Jesus.

Nonetheless, Niemöller’s public objections to the Nazification of the Church were enough to get him arrested in 1937.

Then, in March 1938, he was sent to Sachsenhausen.

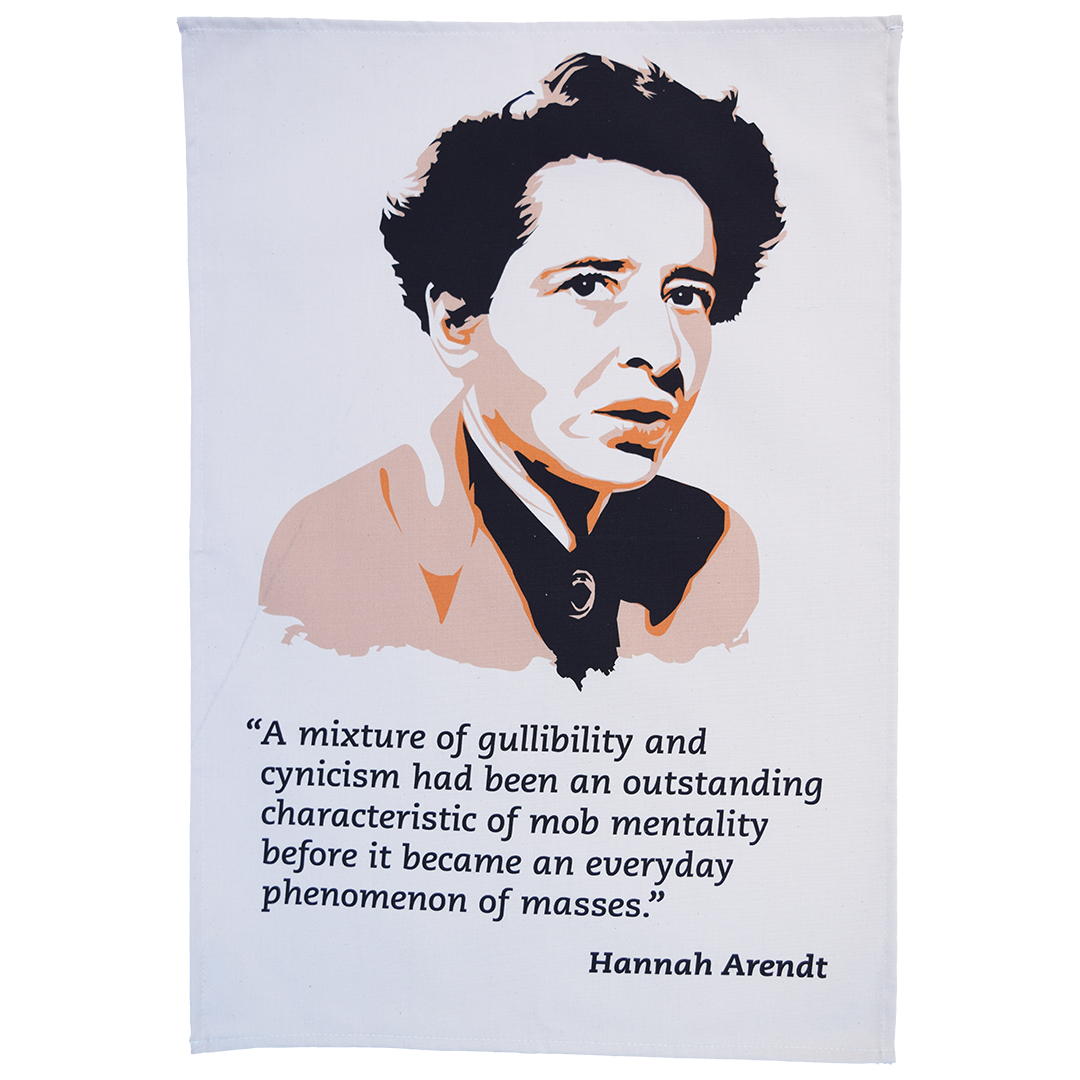

Hannah Arendt was arrested and imprisoned by the Gestapo for her research into antisemitism under Nazi rule.

Click to view our Hannah Arendt tea towel

Niemöller spent seven years in concentration camps, first Sachsenhausen and then, from 1941 onwards, Dachau. He was freed by US troops in April 1945.

In 1947, in light of his past support for the regime, the Allies decided not to recognise Niemöller as an official victim of the Nazis.

So, what exactly does Martin Niemöller mean to radical history, if neither a victim nor a hero?

Well, unlike many in post-war Europe, Niemöller never disputed his own complicity with fascism.

In October 1945, he helped initiate the ‘Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt,’ by which the German Evangelical Church admitted to not having done enough to oppose Hitler.

And, a year later, he wrote one of the most famous poems of the era:

“First they came…” was Niemöller’s own confession.

History is full of the names of those who took a stand against fascism: Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht; Sophie and Hans Scholl; the

International Brigades in Spain; the Warsaw Ghetto insurrectionists, to name but a few.

Meanwhile, Martin Niemöller - and millions of others in mid-century Europe - had stood aside.

The poem tells us what happens when we look the other way, when people fail to practise solidarity with one another.

The lesson is simple: when the fascists come knocking for someone different to you, don’t be relieved – be rebellious.