The Year Women Won the Vote

Posted by Pete on 6th Feb 2018

Today we're thinking about the centenary of the 1918 Representation of the People Act, which gave (some, but not all) women in the UK the right to vote for the first time.

It was a real political revolution.

Along with the 1928 Equal Franchise Act which allowed all women to vote on the same terms as men, the 1918 Act continues to be the legal reason why there is no gender difference in voting rights in Britain today. It's one of the legal foundations of our democracy.

And the significance of it was obvious straight away.

Sign up for new post updates here

A new parliament after 1918

Very soon after the 1918 Representation of the People Act, some of the most radical women of modern British history turned into some of the most radical MPs in modern British history.

Constance Markievicz, a hero of the Easter Rising and icon of Irish Republicanism, was elected a Sinn Fein MP in December 1918 - becoming the first woman elected to Parliament (like today's Sinn Fein MPs, she didn't take up her seat).

See all the Suffragette anniversaries this year in our new calendar

In 1924, the inimitable Ellen Wilkinson – who would go on to play a prominent role in the 1926 General Strike, the Jarrow Crusade, and British support for those fighting Franco in Spain – was elected Labour MP for Middlesbrough.

With her ginger hair and bright red dress, Wilkinson announced defiantly to the House of Commons in her first speech:

"I happen to represent in this House one of the heaviest iron and steel producing areas in the world – I know I do not look like it, but I do."

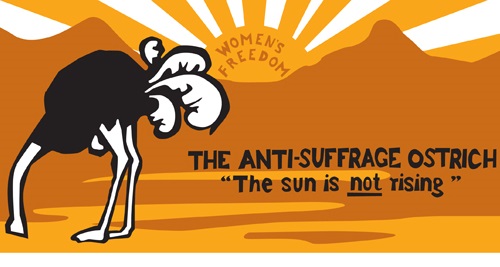

A backlash against gender equality

One hundred years ago, this overhaul of political life was disturbing to a lot of people (mainly men, surprise, surprise!).

Claiming that women weren't mentally kitted-out to participate in politics, many men had fought long and hard against universal suffrage.

Dr James Burnett, for example, wrote in 1895 that girls always fell behind intellectually at school because of their "disordered pelvic life."

Putting it kindly, all of this anti-suffrage literature was rubbish and everyone responsible for it was a moron.

As a man, I've grown up being surrounded by the proof of this.

My big sister, Siobhan, for example. She's light-years smarter than me, and in my life I've never seen anyone get the better of her in a debate – I've long since given up trying to myself. And yet in 1917, I could have voted and she couldn't.

Then there's my cousin Fiona. She's pretty big in the Irish 'Repeal the Eighth' movement against heavy anti-abortion laws in the country.

Beyond my family, so many of those I've had the chance to campaign for and work with over the years in student and Labour politics have been women. Peerless operators and firebrands the lot of them.

I could go on (and on, and on) but you get the basic point: if the franchise were distributed on merit, it's foolish men like James Burnett with his pseudo-scientific talk of 'disordered pelvic life' who should have been worried, not women.

But, of course, the disenfranchisement of women wasn't about merit. That was just something that was said to make the policy look loftier than it was.

It wasn't a concern for the quality of citizenship which inspired men against female suffrage, but a concern for their own power.

Women voting and standing for Parliament would threaten the patriarchy as it had never been threatened before, forcing their social and political interests into British politics where previously they could be completely ignored.

These interests were, for many women, at odds with the conservatism, capitalism, and imperialism to which the contemporary Edwardian establishment was directed.

The rich men who dominated Britain feared suffrage. And they were right to be afraid.

See new Suffragette heroes like Annie Kenney depicted on our Suffragette calendar

New Possibilities for pro-women legislation

First came the revolutionary women MPs mentioned earlier, then, as they grew in number, came the revolutionary pro-women legislation.

Could the 1967 act legalising abortion really have been passed if the government didn't have to be sensitive to women voters? What of the 1975 Act prohibiting discrimination on grounds of sex in employment and service provision?

The 1918 Representation of the People Act was a mighty victory for feminism and for democracy in Britain.

But the job wasn't, and (crucially) isn't, done. British democracy is still incomplete.

Sixteen to eighteen-year-olds, for example, remain without the vote while being able to work, pay taxes, and serve in the military.

Beyond the formal, electoral franchise there are gaping holes as well.

What about industrial democracy? In most cases workers remain without a say in how their firms are run.

And what of those millions in the developing world, whose lives are so often effected by British companies and, sometimes, the British military? They have little influence on British politics.

I had to end on a note of agitation.

I'd surely be disappointing those early Suffragettes if I didn't.

Their concerns, after all, were what we would now call 'intersectional' – concerning not just politics, but also economics and society. Not just women, but all oppressed groups.

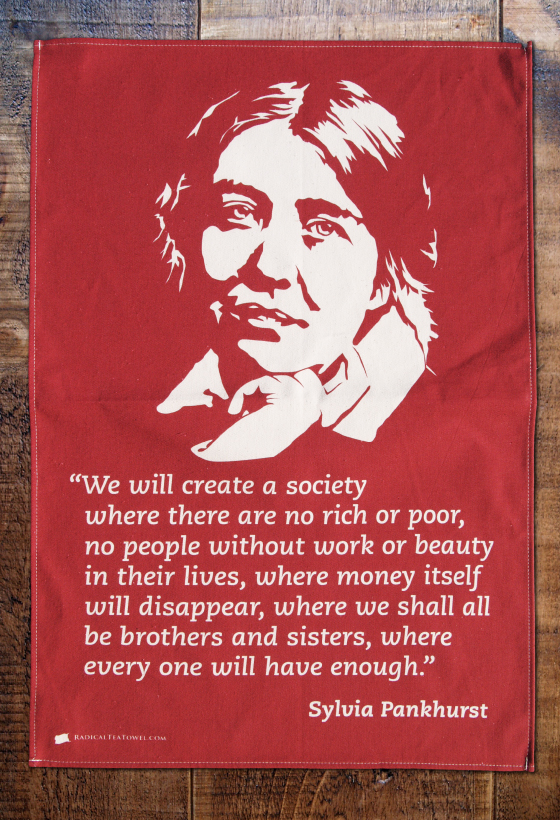

The great Sylvia Pankhurst once wrote:

I doubt Sylvia would have looked at modern Britain and thought this vision had been achieved.

As a result, she would have probably have told us: "It's all well and good celebrating our victory a hundred years ago, but don't forget the work still to be done."

"Deeds, not words."

1918 was a big victory – now to win the war, right?