100 Years Since the Great War: Mutiny on the Front

Posted by Pete on 11th Nov 2018

The 17th century poet laureate, John Dryden, once wrote: "Nor is the people's judgement always true: The most may err as grossly as the few."

It was a cautionary couplet on the principle of majority rule.

Many progressive-leaning people may feel Dryden's words are instructive today amid Britain's ongoing departure from Europe.

Plenty of radicals felt the same back in 1914 over a British entry into Europe - not a cooperative European organisation, but a European war.

Silenced opposition to the Great War

When Herbert Asquith's Liberal government went to war with Germany, a mood of rabid nationalism swept Britain - socialists, liberals and feminists as well as the predictable Tories.

Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst, for example, set the WSPU and the suffrage movement against the expelled Sylvia Pankhurst for her refusal to support the government.

Arthur Henderson led a large faction of the Labour Party against the likes of James Keir Hardie and George Lansbury, who were being heckled across the country as they denounced the war.

It was a similar story in Europe.

The German socialists - who held a majority in the 1914 Reichstag - voted to give Kaiser Wilhelm his war credits to the outrage of true internationalists like Rosa Luxemburg.

And in France, the socialist leader Jean Jaures was assassinated by an ultra-nationalist for his stand against the conflict.

But by the end of World War One - a hundred years ago today - the scene of popular opinion had changed. The lies used to dupe the people of Europe into war had collapsed.

Dissent to the Bloodshed

This sea change hadn't happened automatically. It was brought about by resistance and dissent.

During the four years of bloodshed, a rich heritage of anti-war politics built itself up across the world.

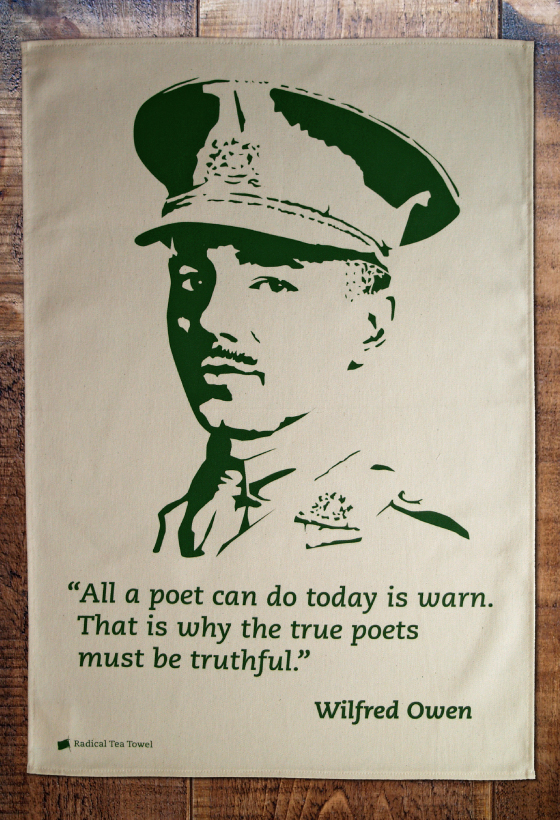

In Britain we had our renowned war poets, ridiculing the promise of glory in recruitment propaganda. Men like Wilfred Owen painted the horror and futility of war in verse from their dugouts in France.

After the States joined in 1917, American radicals like Emma Goldman and Eugene Debs rallied tirelessly against the draft. Most of them were (unconstitutionally) imprisoned or deported for their courage.

But it wasn't across the pond that you'd have seen one of the most formidable acts of resistance to the war. It was across the Channel.

By early-1917, the French - who had gone to war eagerly, hoping to recover Alsace-Lorraine from Germany - were probably suffering more from the war in Europe than anyone but the Russians.

The Western Front tore through the towns and villages of Champagne and the Pas-de-Calais, not Kent or Saxony. And that Front was already the grave of more than a million French troops.

France's soldiers - or 'Poilus' ('hairy ones'), as they were affectionately known - had been taken to the limit of what they would endure at the hands of German firearms and their own wealthy generals' avarice.

In April 1917, they were taken past that limit.

General Robert Nivelle promised his troops a quick, war-winning offensive on the River Aisne. It was the same promise which had been made to German troops invading France in 1914, and to British troops on the Somme in 1916. Both times the promise was broken, and it was about to be broken again.

The French suffered over 187,000 casualties. The war was not won.

This time, however, the soldiers weren't going to tolerate their lives being wasted by their officers. With revolution in the air after Russia overthrew the Tsar in February 1917, the poilu soldiers took action.

Mutany at Aisne

In 1967, with the declassification of war ministry archives, it was revealed that tens of thousands of French soldiers had refused to cooperate after the battle on the Aisne. Over half the divisions in the French Army took part in this mutiny to some degree.

The men said they would defend their positions if attacked, but they refused to be thrown to a pointless death.

Beginning with the 21st Infantry Division, unit after unit of Frenchmen refused attack orders, demanded more leave, and even sang the socialist Internationale.

It was an inspiring demonstration of resistance to the WWI officer-caste by battle-hardened soldiers.

The mutineers of 1917 didn't manage to bring an end to the war though. Marshal Pétain (who would go on to sell France to the Nazis in 1940) put them down violently - mass arrests and trials were followed by prison and worse. 26 were executed.

But there remains a message of hope in the mutiny: that the ruling class might delude us sometimes, but that delusion doesn't last. When we realise the truth of things, we are capable of taking control of our destiny.

Though the French mutineers didn't win, they revolutionised the Western Front. Pétain, terrified of his troops' discontent, wouldn't launch a major offensive for another year - he knew the men wouldn't follow him.

What's more, it was a similar mutiny of German sailors at Kiel in 1918 which triggered the overthrow of the Kaiser and Germany's move for peace.

So, if there is a narrative to take from the Great War a century after its conclusion, it's not that it was a 'tragic but necessary' sacrifice.

It's that the working people of Europe gradually woke up to the fact they'd been duped into a war which benefited only the elites, and were then able to take popular action - mutinies and strikes, protests and pamphlets - to end it.