The 'Independent Group': History repeating itself, but not in the way you'd think...

Posted by Pete on 24th Feb 2019

The news over the past few days has been covered with the departure from the Labour Party (and now also from the Tories) of a small number of MPs calling themselves the ‘ Independent Group’.

The talking-heads buzzing round this story have been pretty eager to draw comparisons between this group and the ‘Gang of Four’ (Roy Jenkins, Shirley Williams, David Owen, and Bill Rodgers), who quit Michael Foot’s Labour in 1981 to form the so-called ‘Social Democratic Party’ (eventually merging into the Liberal Democrats).

The Tale of Ramsay MacDonald

Foot, like Jeremy Corbyn, also represented Labour's left flank, while the ‘Gang of Four’, like Chuka Umunna et al, had been on opposite end of the party politically. So you can see why people have been drawn to the analogy.

But the ‘Gang of Four’ wasn’t the first breaking off of Labour’s right-wing in the party's history.

It happened in the hot and desperate summer of 1931; the Labour Party was in power (just about – they had no majority in the Commons), and Ramsay MacDonald was its Prime Minister.

Debonair and deeply intelligent, MacDonald was a Labour Party icon.

Out of the depths of Scotland’s 19th century rural working class, he was still a young man when he started to make a political name for himself in Keir Hardie’s Independent Labour Party during the 1890s.

Prominent in the parliamentary efforts of the Labour Representation Committee (established in 1900 and the immediate forerunner to the modern Labour Party), he was elected MP in 1906.

In 1914, MacDonald won himself serious moral credit by joining Hardie, Sylvia Pankhurst, and a (shamefully) small number of other British socialists in refusing to support the First World War.

Popular disenchantment with the war saw MacDonald back to the top of Labour – he was elected leader in 1922. In 1923 he became Labour’s first Prime Minister – a post he regained when Labour won the 1929 General Election ( the first with a gender-equal, non-property franchise).

Working-class, politically successful, a bit of moral backbone – the Ramsay MacDonald chapter of Labour’s history was looking good.

Then came the Wall Street Crash.

Forming a National Government

Just a few months after MacDonald re-entered 10 Downing Street, the catastrophic failure of American capitalism threw the global economy into depression – the Great Depression.

Britain wasn’t spared – the 1930s would be the decade of mass unemployment and public actions like that of the Jarrow Crusade.

“But Ramsay MacDonald’s at the helm,” the British working class could say, “that’ll soften the blow.”

They were, tragically, wrong.

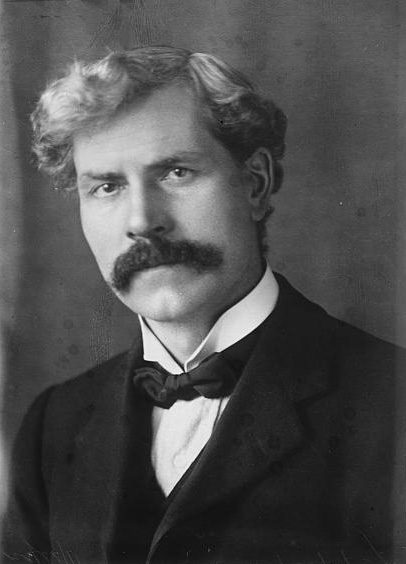

Ramsay MacDonald went from Labour icon to enemy after betraying his party over austerity.

Image credit: United States Library of Congress

The ‘orthodox’ (read: Tory) response to economic downturn had always been cuts to social spending (how little has changed…) and the financiers in the City of London and Bank of England were pushing MacDonald’s government to do the same.

Ignoring the smarter call from John Maynard Keynes for public investment in jobs to restart the economy, MacDonald wanted to go with the bankers’ favoured choice of austerity.

But the bulk of his Labour MPs didn’t agree. They saw cuts as an attack on the very workers whom Labour had been elected to protect; in order to solve an economic crisis created by the very bankers whom Labour had been elected to resist.

All of this came to a head in August 1931, when MacDonald proposed a 20% cut to unemployment benefits to his Cabinet.

The Cabinet split – no fewer than eight ministers, including former leader Arthur Henderson, were threatening to quit rather than take part in an attack on the jobless when almost three million Brits were out of work.

MacDonald, accepting he could not pass the policies he wanted to against this kind of moral opposition, gave his resignation to King George.

‘Unbelievable’, ‘incredulous’, ‘horrifying’ – take your pick. None of them do justice to what happened next.

MacDonald's Great Betrayal

In the behind-the-scenes talks following his resignation, Ramsay MacDonald, leader of the Labour Party, became Prime Minister again – at the head of a Tory Cabinet.

He called it ‘the National Government’, claiming it to be a coalition, but it was almost entirely based on Conservative support – the only Party which would gladly vote through the brutal austerity program MacDonald wanted.

Labour, baffled, quickly expelled MacDonald and the two ministers he’d taken with him from the Party, but the damage was done.

‘National Government’ PM Ramsay MacDonald called a general election – entering it with the pitiful few who’d followed him out of the Labour Party under the name ‘National Labour’ (arm-in-arm with the Tories who were the soul of his new movement).

The party MacDonald left was decimated at the polls, with Stanley Baldwin’s Conservatives reaping the electoral reward. Labour, under Arthur Henderson, lost 235 seats – including Arthur Henderson’s. It retained just 52 MPs.

It was hardly a surprising result, either. What else was going to happen when the Prime Minister – who’d been Labour’s leader just a month earlier – was telling people not to vote for his former party?

Though MacDonald's Tory backers allowed MacDonald to stay in Downing Street for a few more years, his once proud reputation was done.

Even the typically reserved Clement Attlee called MacDonald’s 1931 defection “the greatest betrayal in the political history of this country,” and went so far as to draw parallels between MacDonald’s ‘National Government’ and fascism in the way it undermined multi-party democracy.

When MacDonald at last resigned in 1935, his broken speech was met by the call of “Sit down man! You’re a bloody tragedy,” from the Labour benches.

MacDonald’s tragic political story was over, remembered not for his courageous moral stand against World War I jingoism but by his “great betrayal” of 1931 – the first great split in the Labour story, half a century before Roy Jenkins and his friends became the ‘Gang of Four’.

Post MacDonald, the Labour Party was renewed

Despite this quite sad story from the 1930s, those readers who are worried for the Labour Party because of recent events have real cause for hope.

For one thing, it’s important to note that Ramsay MacDonald’s departure did so much electoral damage to Labour because he was Party leader, not just a backbencher.

What’s more, leader or not, MacDonald’s departure did only one election’s worth of damage – the 1930s saw the Labour Party renew itself.

Propelled forward by the hard work of men and women like Clem Attlee, Ellen Wilkinson, and Aneurin Bevan, Labour won a historically unprecedented landslide in 1945 – which was only the second election since the MacDonald disaster.

Disagreements have come about, and splits have sometimes followed, but for 120 years the Labour Party has kept marching on. As its anthem goes:

“We’ll keep the Red Flag flying here.”

It’s a song of determination – suitable for a party which has never quit.