The Legacy of Wilfred Owen

Posted by Pete on 11th Nov 2017

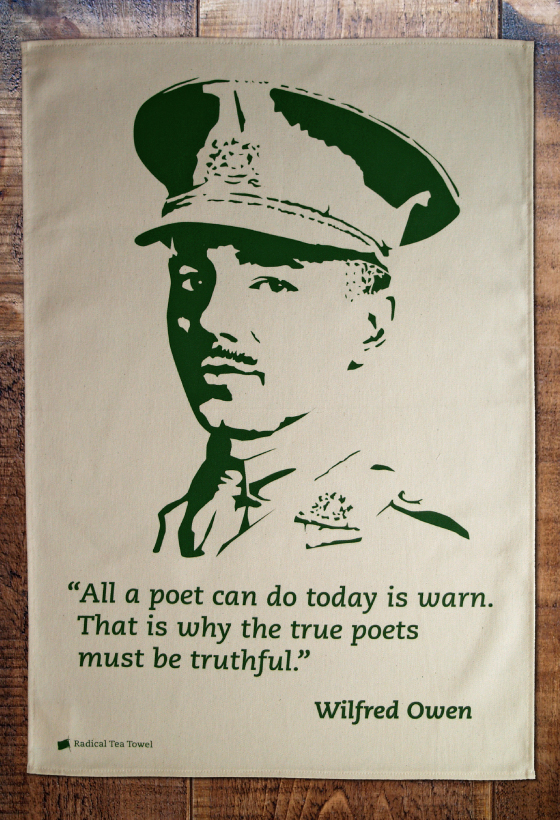

99 years ago today, an armistice was signed between Britain and Germany. Here's the war poet, Wilfred Owen:

"If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old lie: Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori."

If, like yours truly, you don’t speak Latin, "Dulce et Decorum est pro patria mori" means "it is sweet and right to die for your country."

It was Wilfred Owen’s experience of the hell that was World War One which helped him see the lie behind this statement.

Above: our Wilfred Owen-inspired tea towel

The tragic death of Wilfred Owen

1st Lieutenant Owen wrote this in 1918 while convalescing in Scotland, having developed shell-shock in France after being blown up in no-man’s-land.

Along with millions of other 'Tommies', the reality of industrial warfare transformed Owen from a willing participant into a critic of the British war effort and the jingoism which came with it.

Having returned to the front from Scotland, Owen was killed in action crossing the Sambre-Oise Canal in northern France on the 4th November 1918.

Seven days later, four years of slaughter came to an end.

A legacy through words

It’s a tragedy that Owen didn’t survive the Great War. But we can be thankful that his poetry did.

To this day, it's provided the British peace movement with one of its best, most persuasive playlists.

Empty platitudes like 'national honour' are a lot less stirring to those who've read Owen’s account of an actual gas attack.

By putting the first-hand reality of war into vivid detail, Owen's poetry has helped those who've argued for peace ever since.

In this way, the Great War arguably helped radicalism. And not just through poetry.

Major Clement Attlee, the future Labour leader, served in Iraq and at Gallipoli.

Having seen so many of his working-class soldiers killed and maimed, he wanted a reward for them in peacetime. He decided that there should be stronger social security and jobs – 'A land fit for heroes'. This much was pledged by David Lloyd-George's government, but not delivered.

Attlee set out to finish the job himself in 1945.

Post-War Progressivism

War, then, can be a seedbed of progressive politics. People experience its brutality and come home – if they come home – ready to demand stuff from the rich old men who sent them there. It could be peace, it could be social reforms, it could be the vote.

This doesn’t mean we should support war, of course.

The great Tony Benn – himself an RAF pilot – said: "Never forget that the British labour movement has always been in favour of peace."

We don't like people dying so the rich can keep their colonies and trade routes. We’re really not okay with that.

But the examples of Owen and Attlee's experience of war do, at least for me, offer a better way to remember those who died.

Without these examples I'd assume my mum's great uncle, Michael Sachs, had died needlessly in the mud at the Battle of Loos (25th-28th September 1915).

But instead I think of how his courage and suffering perhaps gave men and women the extra justification they needed to demand - through poetry or politics - peace and prosperity for all.