Why Wilberforce and Equiano's Campaign Against Slavery Still Resonates

Posted by Pete on 12th May 2019

In 1789, the abolitionist leader William Wilberforce struck upon a vital truth of global economics – the West became developed by under-developing everywhere else.

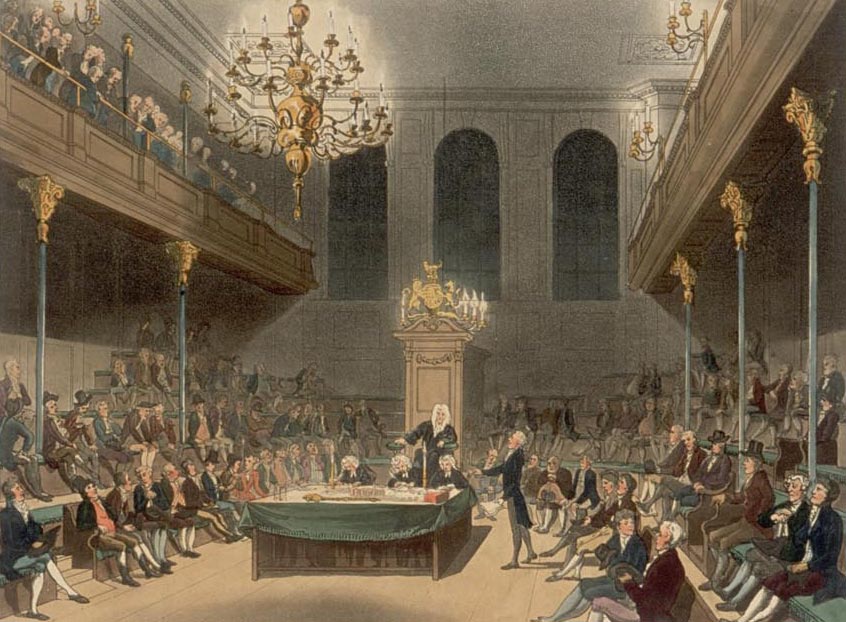

William Wilberforce ranks, along with the likes of Aneurin Bevan and Tony Benn, as one of the most skilled orators in the history of the British Parliament.

One man who watched Wilberforce speak in the Commons remembered how “I saw what seemed a mere shrimp mount upon the table; but as I listened, he grew, and grew, until the shrimp became a whale.”

So, it was a big step forward for British abolitionists when Wilberforce agreed to put his voice at the service of their cause – the defeat of the barbaric slave trade which coursed through the British Empire throughout the 18th century.

William Wilberforce joins the fight for abolition

In May 1787, encouraged by fellow abolitionists like Thomas Clarkson, Wilberforce agreed to lead the campaign in Parliament for abolishing slavery in the British Empire.

Two years later, the first abolition bill was set before the House of Commons.

Exactly 230 years ago today, on 12th May 1789, Wilberforce made his first parliamentary speech against the slave trade.

Now remembered by the title "Let us Make Reparation to Africa", Wilberforce's speech denounced how Britain’s voracious and unending rampage for slaves had ruined the African continent, imploring his fellow MPs:

“Let us put an end at once to this inhuman traffic – let us stop this effusion of human blood.”

Wilberforce’s speech fired the starting gun for a forty-year legislative campaign against the institutions of British slavery.

The 1789 attempt to abolish the slave trade, and then many more after it, were defeated. It was not until 1807 that Britain’s plutocratic Parliament, drenched in money from the slave trade, would pass Wilberforce’s bill.

It then took another twenty-six years to conquer the institution of slavery itself – which was outlawed throughout the British Empire in 1833.

What the abolition campaign can teach us about todays world

Returning to Wilberforce’s legendary oration in 1789, there was, buried in his speechcraft, a point about global development which was literally centuries ahead of its time.

Wilberforce, in his own way, recognised that ‘underdevelopment’, as we call it nowadays, is not just a state of national economic wellbeing – but a process done by somewhere to somewhere else.

He opened by telling his peers:

“All improvement in Africa has been defeated by her intercourse with Britain [i.e. the slave trade]…it is we ourselves that have degraded them.”

Africa, in other words, was underdeveloped by Britain and the countless other colonial powers who pillaged it intentionally as part of a "scramble" to get rich.

Heirs to Wilberforce

A century and a half after William Wilberforce, this argument started to light up political conversation again.

‘Third World’ intellectuals and their allies, in the postwar period, began to argue that economic development couldn’t be solved in a national framework, because it was the result of international processes.

Just as Britain achieved its own development by under-developing Africa with the slave trade, this process of parasitic growth in the ‘First World’ was still going on in the 20th century through things like unequal trade relations between the US and Latin America,

neo-colonialism in the Middle East, and the management of the world economy by a cartel of Western governments through organisations like the IMF and World Bank.

This revolutionary theory is called ‘World-Systems Theory’ by some, ‘Dependency Theory’ by others. It was created by outstanding economists like Immanuel Wallerstein and Andre Gunder Frank.

Others, like the Uruguayan, Eduardo Galleano, and the Guyanan Walter Rodney, brought the economics into history and literature with beautiful books like Open Veins of Latin America (1971) and How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1972).

The essential point being made over and over again was that everything is connected – specifically, that the wealth and development of the West is tied up with poverty and underdevelopment in other parts of the world.

In his critique of slavery, then, William Wilberforce stumbled into a radical truth concerning the real nature of the global economy, both then and now.

We see it in the poisonous historical legacies of slavery and colonialism, along with more recent phenomena like disaster capitalism, where hedge funds buy up millions in sovereign debt from some of the most distressed places in the world — then force governments to make painful spending cuts to essential public services for their people, rendering the state more or less useless.

If we were to extrapolate Wilberforce’s crusade against the slave trade in the 18th century to the relationship between the rich and powerful and the developing world in the 21st, it would go something like this: to solve global poverty, the solution isn’t tinkering within national economies or charity. It’s a radical restructuring of the global economy and its distribution of wealth.

To paraphrase Wilberforce: those of us enjoying the comforts and prosperity of the Western world today can choose to look the other way, but we can never say that we did not know.

Read on for more about Wilberforce, Equiano, and other stories from Radical History