We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

A World Beyond War: How Gernika Inspired a Movement

The story of how the bombing of Gernika helped to spark a global anti-war movement that continues today

On 26 April, 1937, it was market day in Gernika. 10,000 people filled the ancient Basque capital, buying and selling, chatting and joking.

Then, at half past four in the afternoon, a wave of bomber aircraft arrived to destroy the city. It was followed by another wave, and another: Heinkel-111s sent from Nazi Germany and Savoia-Marchetti 79s from Fascist Italy.

They were in Spain to help Francisco Franco overthrow the democratic government in the Spanish Civil War. This was the iron fist of fascist internationalism.

This design is based on a campaign poster by The Artists International Association in Britain, encouraging support for the Republican cause

Click to view our Help Spain tea towel

Tens of thousands of Spanish people – workers, trade unionists, soldiers, civilians – had already fallen victim to this unholy fascist alliance. Now it was Gernika’s turn.

After the five waves of bombers had come and gone, the town was left in ruins. Between 150 and 1600 people had been killed. (The number is disputed).

The Basques loved Gernika, and General Franco hated the Basques.

Nestled in Biscay province, just east of Bilbao, the town was the historic Basque capital. The Basque traditions of local self-government can be traced to the ancient “Gernikako Arbola” – the tree of Gernika – where people used to gather around to deliberate.

Those traditions had bloomed in the struggle to defend the Spanish Republic. The Basques were some of its most determined fighters.

At first sight, the anti-fascist alliance between the Republican government and the Basque provinces might seem peculiar.

The Basques had a reputation for conservative, Catholic belief. The Communist firebrand, Dolores Ibárruri, whose dad was a Basque miner, was a little unusual in this context.

By contrast to the traditionalist Basques, the Republic was known for its anti-clerical socialism, and was backed by the left-wing volunteers of the International Brigades.

Dolores Ibárruri was a Spanish Republican remembered particularly for her slogan ¡No Pasarán! from a speech she made during the Battle for Madrid

Click to view our No Pasarán! tea towel

But the Republican government was also committed to a multicultural vision of Spain, which recognised the cultural and political autonomy of its constituent peoples, like the Catalans and the Basques.

That commitment was enough for the Basques, who fought hard for a Republican victory.

On the other side were Franco, Hitler and Mussolini.

The Spanish Generalissimo fought his insurrection as a Catholic Crusade against godless Bolshevism.

But it was also violently centralist. The Spanish Right believed in just one Spain, dominated by Castilian culture, in which nationalities like the Basques and Catalans would be forgotten.

So when Franco’s forces advanced northward into the Basque Country in early 1937, his commanders took the opportunity to devastate the region.

After the fascist bombers destroyed Gernika, the way was cleared to take Bilbao. Franco’s attention could then turn to Madrid.

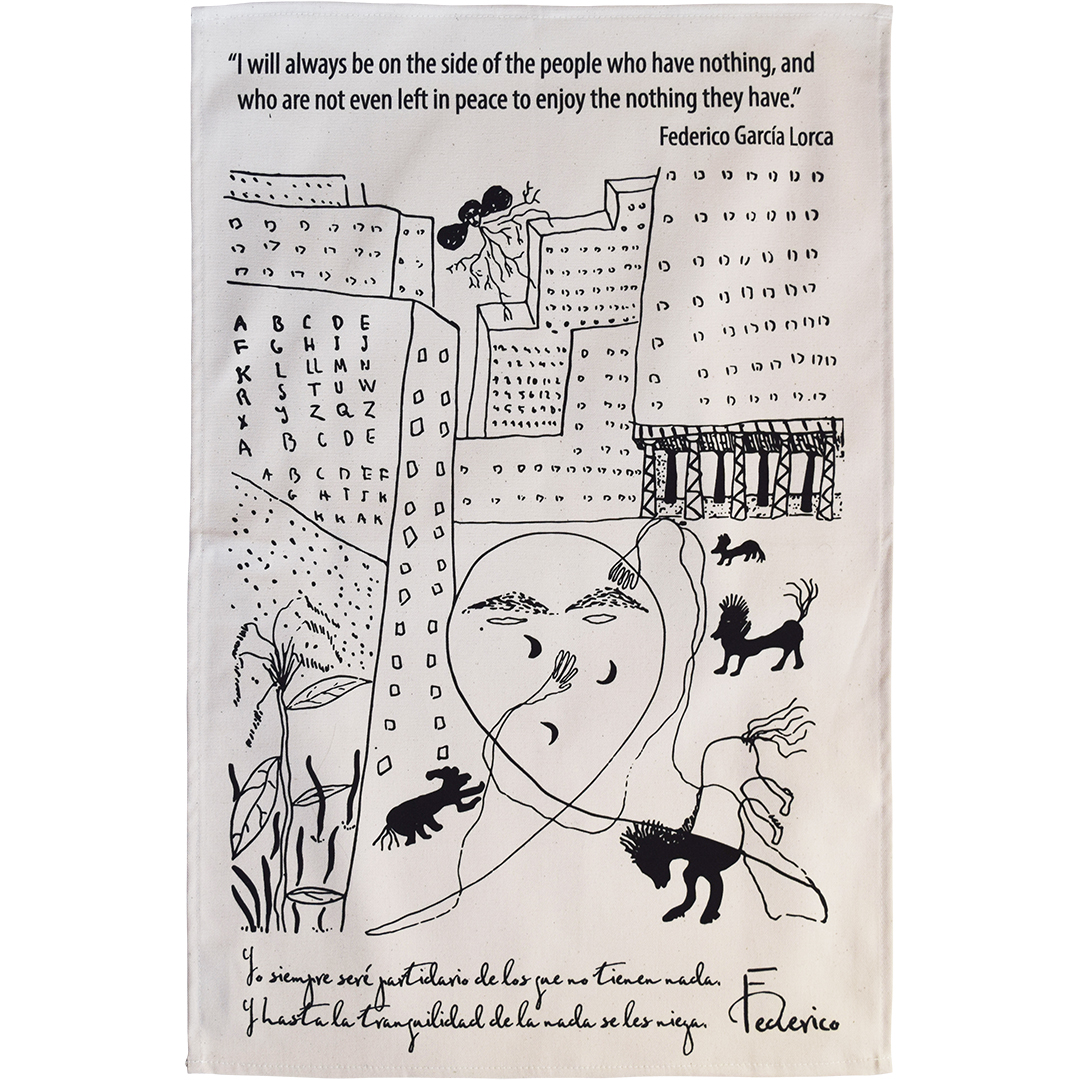

Lorca is thought to have been assassinated by Nationalist militia in August 1936, making him one of the earliest casualties of the Spanish Civil War

Click to view our Federico García Lorca tea towel

With the defeat of the Spanish Republic in 1939, democracy died in Spain.

Over the following decades of Francoist rule, the Basques experienced cultural persecution, militarised policing, and endless states of emergency. They were also at the forefront of political resistance to the fascist state.

Gernika, meanwhile, became a symbol for the global anti-war movement.

The destruction of Gernika in April 1937 caused a paradigm-shift in how people understood war.

Pablo Picasso, distraught, was inspired to paint his harrowing masterpiece.

It was now suddenly understood that war was no longer a purely military affair. Airborne bombers flew past the frontline, to target urban centres, where they could destroy markets and trams, hospitals and schools.

Wars now had no limit: anyone, it seemed, could be a target.

In the decades since the Spanish Civil War, the town of Gernika has united with other places decimated by bombing to agitate for world peace.

In February 2003, elderly survivors of both the fascist bombing of Gernika and the Allied fire-bombing of Dresden in 1945 came together to protest against the imminent Anglo-American bombardment of Iraq.

And in 2007, the Japanese Mayor of Hiroshima, one of two Japanese cities annihilated by U.S. nuclear bombs, reflected:

“Gernika was the point of departure, and Hiroshima is the ultimate symbol. We must find ways to communicate to future generations the history of horror that began with Gernika… The solidarity we feel today derives from our shared experience of the horror of war, and this solidarity can truly lead us toward a world beyond war.”