Living in Hope: The Spanish Transition to Democracy

Posted by Pete on 29th Oct 2022

The story of how Spanish fascism came to an end and democracy finally prevailed

In March 1939, after a heroic defence, Madrid fell to the armies of Francisco Franco. A few days later, the fascist dictator proclaimed victory in the Spanish Civil War.

The bad guys had won. It was all over.

Or was it?

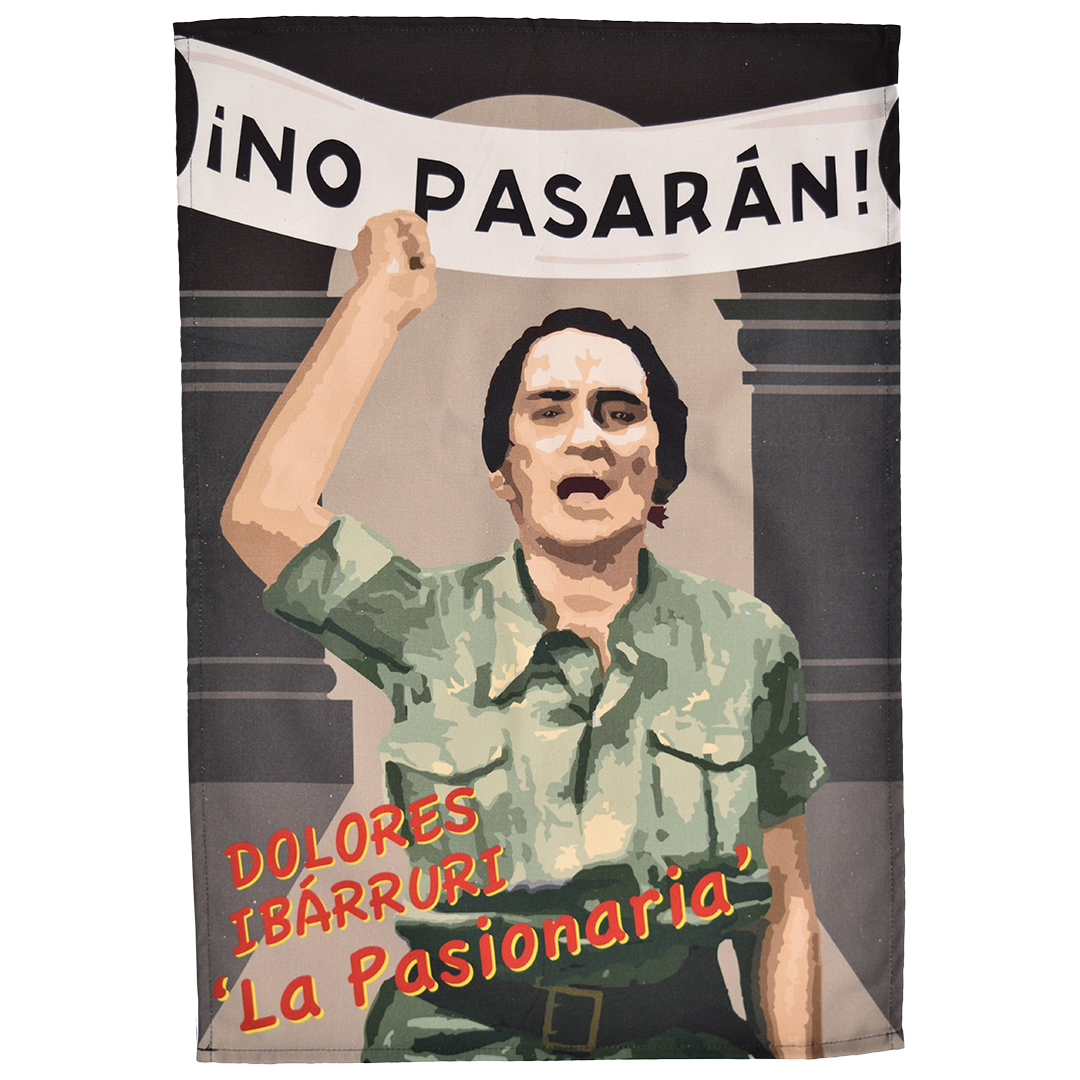

When Franco's forces took Madrid, he supposedly responded to the Republican slogan by declaring "Hemos pasado", meaning "We have passed"

Click to view our No Pasarán! tea towel

After three years of fighting, the Spanish republican state and its armies had been defeated in battle, yes. Hundreds of thousands of its soldiers and civilians had been killed by Franco and his allies, Hitler and Mussolini.

But many more survived. Spanish leftists and their allies, who had fought for the Republic, lived on in Spain and in exile.

And they lived in hope.

Franco was setting up a brutal dictatorship in Spain, but he was hardly secure.

Just months after he conquered Madrid, World War 2 broke out in Europe. Franco was a keen supporter of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. But Spain didn’t join in.

Then, when the Allies started to gain the upper hand in 1943, Franco began looking nervously at his border with France.

If the Allies were fighting a war to liberate all Europe from fascism, surely he was a target?

The thousands of Spanish leftists and republican exiles who served in the

French Resistance certainly thought so.

The story of European anti-fascism is a story of international solidarity, from the International Brigades fighting Franco to the Spanish leftists fighting in the French resistance

Click to view our Spanish Civil War tea towel

In October 1944, with France mostly liberated, Spanish members of the Resistance launched a 7,000-strong invasion of Francoist Spain through the Pyrenees.

They hoped to hold some Spanish territory long enough to compel Allied forces in western Europe to liberate Spain. But the support didn’t come, and soon enough they were driven back across the mountains.

The lack of support from the Western Allies wasn’t just a matter of resources. It was a matter of ideology too.

Even before Hitler was finished off, the Cold War with the Soviet Union was starting.

Suddenly, it became much more important to the Allies that Franco hated communists, and much less important that he was a fascist who’d allied with Hitler for years.

But even as the prospect of Western support against the Franco regime diminished, the Spanish resistance to fascism continued. In smaller numbers, left-wing guerrillas continued the fight in the mountains into the 1950s.

The fiercely autonomous Basque provinces, which had been a pillar of the Spanish Republic, were a thorn in Franco’s side.

Gernika was a Basque town, and the people there would never forget the horror of the 1937 bombing. And when Franco banned the Basque language, their hatred only grew.

The fascist regime loosened just a little during the 1960s and early 1970s as Franco himself grew older and less involved in government, and student protests began to openly demand change.

And then, on 20 November 1975, Franco died.

Based on our Spanish Civil War tea towel, our Help Ukraine tea towel is out now - with all profits supporting Ukrainian refugees

Click to view our Help Ukraine tea towel

Franco hadn't wanted democratisation, but his succession plans weren’t good enough.

The man designated to become head of the government was assassinated by Basque separatists in 1973. And the choice of Juan Carlos to be crowned King and succeed as head of state came back to bite…

Juan Carlos was not as devoted to fascism as Franco had thought. In fact, he supported reformist elements in the regime who’d come to believe democracy was now unavoidable.

Of course, the dissident opposition – leftists, liberals, nationalists in the Basque Country and Catalonia – were still wary of overtures by career Francoists, led by the new Prime Minister, Adolfo Suárez.

But when serious reforms were finally put forward, the opposition sensed this might be the real thing.

Parliamentary elections were scheduled for June 1977, on the basis of universal suffrage. A blanket amnesty for political prisoners was issued, the rights to strike and unionise were restored.

When the Spanish Communist Party (PCE), the immortal enemy of Francoism, was legalised in April, it was clear the reformers in the regime were serious.

Hardline fascists tried to stop the process, including a failed coup attempt in 1981.

But the momentum was too much: democratic elections in 1977, a new democratic constitution in 1978, and a Socialist government for the first time in five decades elected in 1982.

Spanish leftists had kept the flame of hope alive, and now their hopes had been realised.

For all the difficulties and limitations of la Transición, the Francoist regime was dead. Democracy had a new chance in Spain.