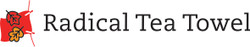

A World in Miniature: Robert Owen's Socialist Utopia

Posted by Pete on 14th May 2024

Born in Wales on this day in 1771, Robert Owen took socialism to the United States

“…the present arrangement of society is the most anti-social, impolitic, and irrational that can be devised…”

The relationship between Wales and America has been in the news during the last few years thanks to the high-profile takeover of Wrexham football club by Hollywood stars Rob McElhenney and Ryan Reynolds.

But the history of Welsh-American connections goes back much further.

In fact, back in the early nineteenth century, it was a Welshman who introduced socialism to the United States.

A prominent Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and socialist, Robert Owen went on to found 'New Harmony', a utopian socialist community in Indiana

Robert Owen was born in Newtown, Montgomeryshire, on this day in 1771.

He was from a middling family in Georgian-era Wales.

Not poor, but not at all rich, Owen’s dad was an ironmonger and his mum was from a farming family.

Owen apprenticed as a draper in Lincolnshire before moving to Manchester - heart of the industrial revolution - at the age of 18.

Recognised as a talent among Britain’s new ruling class of bourgeois capitalists, he quickly rose through the ranks of the textile sector – the most important in Britain’s new industrial economy.

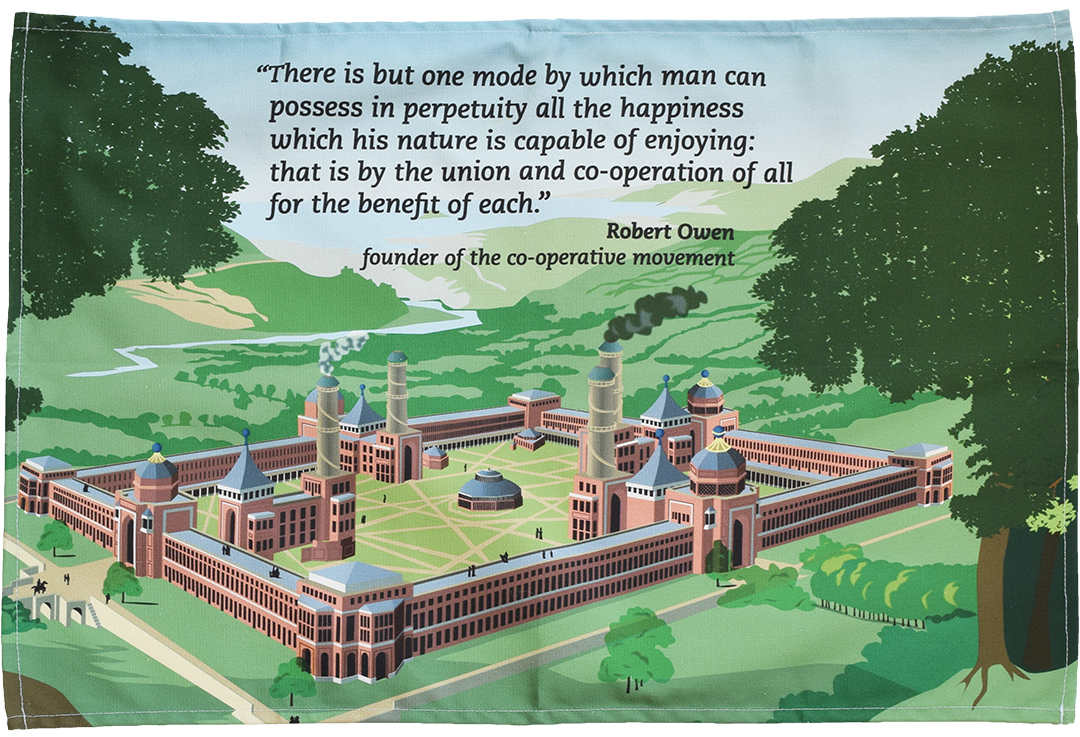

In 1792, at the same time as social revolution was transforming France, Owen was made manager of the Piccadilly Mill in Manchester at the age of just 21.

The end of the eighteenth century was a time of great radical change - not least in France, where the Storming of the Bastille was a pivotal moment in the French Revolution

See the Storming of the Bastille tea towel

But industrialisation in Britain depended upon the violent impoverishment of the working class, stealing common land and forcing them into the cities to work as industrial labourers in dangerously unsafe factories.

Robert Owen was one of the few British capitalists to care about the misery which his class was daily causing for the majority of people.

Indeed, Owen lived in a time when the non-aristocratic bourgeoisie in Britain was still a youthful force in history, capable of critical and creative political thought rather than just profit and self-preservation.

When Owen took over his father-in-law’s textile mills in New Lanark, Scotland, in 1799, he resolved to find a way to reconcile new forms of industrial production with the happiness of industrial workers.

At New Lanark, free education was provided for workers’ children and the workers themselves; corporal punishment, widely used to discipline the workforce of ‘modern’ capitalism, was banned, as was child labour; and Owen’s company stores sold goods to workers at discounted rates.

Owen’s increasingly socialistic business practices were based on the belief that individual outcomes were determined by social conditions, not intrinsic virtue or lack thereof, and that the wealth being produced by industrial capitalism was being produced by its working class, who ought to therefore enjoy a much bigger chunk of it.

Owen and others became convinced that the New Lanark experiment could be replicated; that it might even transform the world.

In order to try out this new, cooperative social model in more detail, Owen travelled to America, where generations of Europeans had projected all sorts of utopias.

Like Thomas Paine, Owen saw the United States as a land of new hope for democracy and justice

See the Thomas Paine tea towel

He arrived in 1824, buying up a town in Indiana which he named ‘New Harmony.’

New Harmony was to be based on egalitarian principles of equal rights and equal duties, common property, and public education.

The idealism of Owen’s project attracted all sorts, what one of his sons called, “a heterogeneous collection of Radicals.”

One participant recalled of New Harmony that

"We had a world in miniature – we had enacted the French revolution over again."

Owen believed that his model of a cooperative, socialist community might save industrial society from the fissures which capitalism had created, by demonstrating a better way of life.

In early 1825, Owen spoke to Congress in favour of his socialist alternative. It was the first time socialism had been put forward so publicly in the U.S.

But in the end, New Harmony didn’t work out, and Owen returned to Britain, where he died in Wales in 1858.

Supporters of capitalist individualism claimed that Owenite socialism had failed because it misunderstood the essentially selfish nature of human beings.

But in reality, Owen’s well-meaning vision of social transformation was simply too small-scale and isolated to survive.

Even if one of the Owenite communities had worked locally, it could not have transformed society as a whole.

Capitalism couldn’t be circumvented through idyllic communes in the American countryside – it had become a global social system which would have to be challenged directly to be overcome.

Nonetheless, even Robert Owen’s left-wing critics recognised him as a praiseworthy predecessor.

He was one of the first in Wales, Britain, and the U.S.A., to confront modern capitalism with the fairer, more just alternative of a modern socialism.