We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

Liberty or Death: The Radical War of 1820

On this day in 1820, a Radical Insurrection swept across Scotland

When the Napoleonic Wars came to an end in 1815, Radical politics was at a low ebb across the British Isles.

From the trial of Thomas Paine in 1792 to the merciless repression of Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen in 1798, visions of a radically better world had been driven to the margins of public life.

But this domestic ‘tranquillity’ - which the Establishment had won for itself with iron and spilt blood - couldn't last forever.

A post-war economic depression set in, prompting industrial unrest across the country.

Thomas Paine was one of the major radical figures of the time, and his book Rights of Man earned the fury of the Establishment.

Click here to view our Thomas Paine tea towel

This unrest was quickly harnessed by the Radical democratic movement as it emerged from the long years of government persecution.

Though the term ‘radicalism’ enjoys generic use today, ‘Radical’ with a capital ‘R’ used to have a more specific meaning.

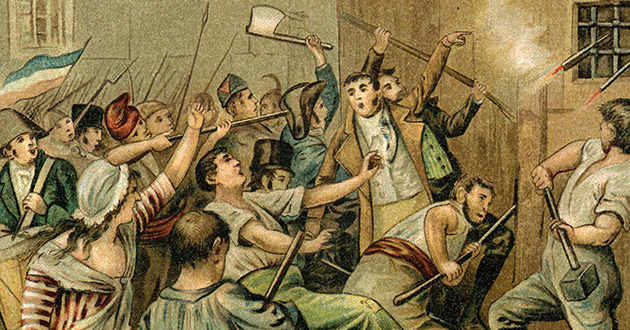

It referred to the agitators inspired by the French Revolution to fight for democratic reform, property redistribution, and the abolition of the monarchy – among other things.

This post-war discontent famously erupted in the industrial metropolis of Manchester, where, in August 1819, thousands of working-class protestors gathered on St Peter’s Field to demand the vote.

Many of them were murdered by government troops and militiamen in what became known as the Peterloo Massacre.

But neither the barbarity at Peterloo nor the arrests and jail sentences which followed were enough to stop the popular discontent.

People across the British Isles were uncowed by what the government had done to the workers in Manchester. If anything, they were even more agitated.

This quotation is from Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem The Masque of Anarchy, written in support of the protesters killed at Peterloo.

Click here to view our Percy Bysshe Shelley tea towel

North of the border in Scotland, Radicals held mass protest rallies in solidarity with victims of Peterloo at Paisley, near Glasgow. Elsewhere, in Stirling, Airdrie, Renfrewshire, Ayrshire, and Fife, other Scots did the same.

With a long tradition of defiance towards government from London, going all the way back to William Wallace and the Declaration of Arbroath, civil disobedience in Scotland was a headache for its English rulers.

More recently, Scottish agitators had been the main source of support for the Jacobite challenge to the Hanoverian dynasty which had taken the English and Scottish thrones in the late-17th century, and the ideals of the French Revolution had enjoyed no less support in Scotland than England.

Indeed, these ideals helped turn the popular discontent which had caused fury at Peterloo in 1819 into the Radical War of 1820 – also known as the Scottish Insurrection.

Beginning in Glasgow on 1st April 1820, a series of Radical uprisings against the Westminster government swept central Scotland and the lowlands.

Rebellion was nothing new to the Scots - the Declaration of Arbroath of 1320 was a battle cry for Scottish freedom and independence.

Click to view our Declaration of Arbroath tea towel

To the extent that this Radical rebellion had leaders, it fell in behind the unimaginatively-named "Committee for Organising a Provisional Government."

It proclaimed:

"Friends and Countrymen! Rouse from that torpid state in which we have sunk for so many years, we are at length compelled from the extremity of our sufferings, and the contempt heaped upon our petitions for redress, to assert our rights at the hazard of our lives… Liberty or Death is our motto, and we have sworn to return home in triumph – or return no more.”

With strong support from unemployed and underpaid weavers (a reliable constituency of Radicalism in Britain during these years), the Radicals skirmished with government troops across Scotland. In Greenock, near Paisley, several unarmed protestors were shot by soldiers.

But alas, the Radicals were soon overcome. Infiltration by government spies and a severe lack of coordination was their undoing.

In the repression which followed, some of Scotland’s most prominent and beloved Radicals were executed by the Crown.

James Wilson was hanged for treason on 30th August 1820 before a crowd of 20,000 people. Andrew Hardie and John Baird were hanged then beheaded in Stirling a week later – the last beheading in British criminal history.

But, once again, Scotland was unbowed. The repression could do nothing to stifle the Scottish radical tradition.

Among several Radicals who managed to flee by ship to Canada in April was William Lyon Mackenzie, born in Dundee, who went on to cause even more trouble for the British Crown by helping lead the Canadian Rebellions of 1837-8.

The flame of Scottish radicalism went on burning, all over the world.