(Radical) Black History Month Part IV: Britain’s Anti-Colonial Tradition

Posted by Pete on 31st Oct 2019

In October 1945, delegates from across the African world gathered in Manchester for the Fifth Pan-African Congress. They resolved to liberate Britain's African colonies and, in the process, wrote the first chapter in the story of anti-colonialism in post-war Britain.

By the 1940s, Britain’s old and creaking empire was at last beginning to fail.

From India to the Caribbean, tens of millions of people were seizing back control of their destiny. Too long had they been held down by British guns and plundered by British fat cats.

Most of the time, this great unfolding of freedom took place in the colonies themselves, through acts of defiance like Gandhi’s salt march and the Easter Rising.

But sometimes, the struggle to pull down the British Empire once and for all was fought in the ‘Mother Country’ itself.

One such occasion was the Fifth Pan-African Congress – held in Manchester 74 years ago.

Pan-Africanism on the Streets of Manchester

In October 1945, eighty-seven delegates from no fewer than fifty anti-colonial organisations came together in post-war Manchester.

They had a single mission: under the rainy skies of northern England, these delegates were going to plan the liberation of Africa.

Since the 19th century ‘Scramble for Africa’, the British Empire had held much of the African Continent, from the Sahara down to the Cape of Good Hope, in an iron grip.

No longer.

The delegates at the Fifth Pan-African Congress – who came to Manchester from all across Africa and the African diaspora – joined together as one to denounce British imperialism and institutional racism in colonial governments, while demanding Africa’s freedom.

The Congress served as a forum to build alliances and momentum which would prove crucial to anti-colonialism in the coming decades.

Many of the principal delegates went onto lead African nations out of their imperial prison – Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, Jomo Kenyatta in Kenya, Hastings Banda in Malawi.

What’s more, the Fifth Pan-African Congress wasn’t just a matter of African politics taking place in Britain – it saw African and British radicalism merge and reinforce each other.

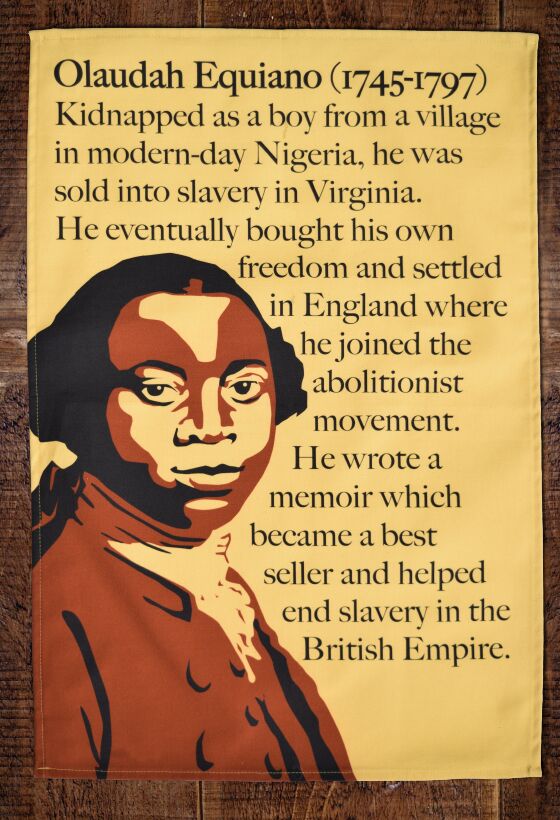

A hero of justice - click to view our Olaudah Equiano tea towel on sale now !

Britain’s Anti-Colonial Tradition

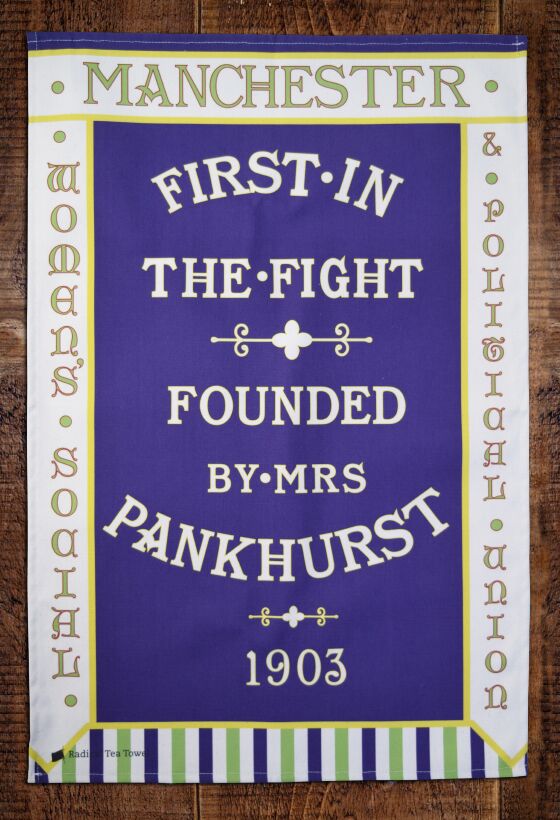

Manchester had been chosen specifically by the Pan-Africanist delegates because of its famously progressive political tradition.

This was the city of Ellen Wilkinson and CLR James; of Sylvia Pankhurst and Friedrich Engels – all enemies of empire and subjugation.

And beyond Manchester, the anti-colonialists of the Pan-African Congress knew they would find as many friends across Britain as they would enemies in Whitehall.

Indeed, the Congress in Manchester sits on the first page of post-war Britain’s most radical tradition – internationalist solidarity against the UK's imperial past.

Within a few years, the anti-imperialist ‘League of Coloured Peoples’ had opened offices in London with the support of British socialists.

The 1950s, meanwhile, saw the Movement for Colonial Freedom created to champion the many anti-colonial struggles which were then being fought against the Empire. Labour Party stars like Barbara Castle and Tony Benn were key figures.

Black citizens were very often the driving force behind these great efforts at anti-colonial solidarity in Britain.

The British Anti-Apartheid Movement was led by black activists like Diane Abbott and Paul Boateng, and the African National Congress leader, Oliver Tambo, made London his base of operations while in exile from the South African regime.

A radical city with a radical history - click to view our WSPU Manchester tea towel

Black History Month and the Internationalist Tradition of Solidarity

Many black Britons were the descendants of immigrants from the African colonies, or had themselves fled the structural exploitation and impoverishment which the British Empire had brought to Africa.

After arriving in Britain, rather than be cowed into silence by the racism of brutes like Enoch Powell, they refused to abandon those still struggling to get by under colonialism in Africa and beyond.

This refusal has sustained the beautiful, blazing flame of internationalism in post-war Britain for decades past and, I’ve no doubt, for decades to come.

As Black History Month draws to a close, we have journeyed from Olaudah Equiano’s abolitionist rallies through to Paul Robeson in the Welsh Valleys; from Mary Prince’s anti-slavery writing in the 1830s to Diane Abbott’s anti-apartheid activism in the 1980s.

So it's fitting to end our Radical Black History Month series by talking about the leadership of a new generation of Britons who pushed the country forward into a new, post-imperial era.

There is far more work to be done – in combating racism here at home, and in doing real justice to the African nations who were robbed of their wealth by Britain and other European powers in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Knowing the full scope of our Radical History, and allowing ourselves to be inspired by it, is a good place to start.