The Eighteenth Century's Che Guevara

Posted by Pete on 8th Apr 2024

Pasquale Paoli isn't a household name, but he was one of the greatest revolutionaries in European history

Long before he became a famous general and declared himself Emperor of France, Napoleon Bonaparte thought of himself as a popular revolutionary.

The young Napoleon agitated for republican and constitutional government rather than arbitrary monarchy, and he dreamed of national independence. Not independence for France, mind you, but rather for his original homeland:

Corsica.

And like every radical in late-eighteenth-century Corsica, Napoleon’s hero was a man called Pasquale Paoli, born on the 6th of April, 1725.

Like Che, Pasquale Paoli was an icon and an inspiration for radicals the world over, from Napoleon to Samuel Adams and Paul Revere

But Pasquale Paoli wasn’t only popular among Corsicans during the 'age of revolutions'.

Despite the fact he made his political name fighting for the independence of a relatively marginal island in the Mediterranean Sea, Paoli was the most famous revolutionary in the world. He was the

Che Guevara of the eighteenth century.

Pasquale Paoli was born in Stretta, in the Morosaglia commune of Corsica.

Back then, Corsica was a relatively unwilling colony of the mainland Italian republic of Genoa.

Paoli’s family, an important member of the indigenous elite, was active in resisting Genoese rule.

In 1729, Pasquale’s father, Giacinto, had played a leading role in the first major rebellion against Genoa, driving Genoese troops back to their coastal fortresses.

Desperate to hold on to Corsica, Genoa called on the kingdom of France to send its troops to reconquer the island in return for a stake in its government and resources.

The Corsican revolutionaries were strong enough to beat Genoa alone, but not the mighty French empire.

The rebels surrendered in 1739, and Giacinto Paoli, along with his teenage son, Pasquale, were exiled to Naples.

The eighteenth century was the age of revolutions, the time of Thomas Paine and Toussaint L'Ouverture

See the new Thomas Paine tea towel

But the Corsicans didn’t give up on their pursuit of independence.

The near-constant international wars of eighteenth-century Europe presented tempting opportunities to undermine Genoese power.

Many Corsican leaders believed that, if they offered to make a foreign princeling their king, then Corsican independence would gain the sponsorship of one of the great powers.

But Giacinto Paoli thought differently.

Exiled in southern Italy, he argued that Corsica should be a republic, not a monarchy, and that it should be governed by its own people, not the dynastic puppet of a foreign empire.

But which Corsican should lead the struggle? Giacinto was by now too old. But Pasquale Paoli was not.

During his time in Naples, Pasquale had received a classical education, which had made him familiar with the republican heroes of the ancient Mediterranean world. And he had also acquired military experience in the Neapolitan army.

He would need both for the life he ended up leading.

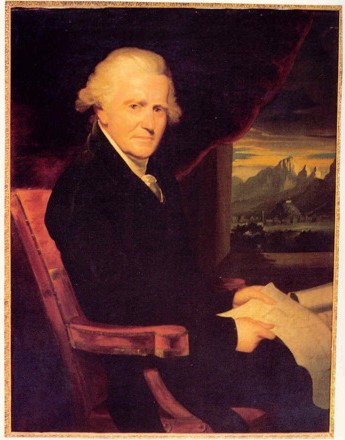

Pasquale Paoli, painted by Sir William Beechey in 1805

In 1754, amid simmering Corsican resistance to Genoese rule, Pasquale Paoli was elected General-in-Chief of the independence movement.

Paoli’s first step wasn’t a military one, though.

Instead, he set about drafting a constitution for a new Corsican republic.

The text included aspects of representative democracy and popular sovereignty, promising the sort of self-government which might get ordinary Corsicans to fight for independence.

And this wasn’t just any constitution. Paoli’s 1755 text was the first written constitution in modern history. That’s why he became so famous among later revolutionaries in Europe and the Americas.

Amid the rocky hills of inland Corsica, Pasquale Paoli showed the world how to fight for representative popular government based on the rule of law.

Paoli’s Constitution worked, too.

It mobilised Corsicans to resist Genoese rule, and by the late 1760s Paoli had created a functioning independent republic.

But then, for a second time, great power politics snuffed out Corsican freedom.

Rather than leave Corsica to its hard-won freedom, Genoa effectively gave the island to France which, despite courageous guerrilla resistance by Paoli’s forces, conquered the young republic in 1768.

Paoli went into exile again, this time in London.

Seeing an opportunity to undermine its rival, France, in the Mediterranean theatre, the British government flattered and sponsored Paoli over the next two decades.

Paoli’s politics seemed to change during this period, such that when he was at last allowed to return to French-ruled Corsica as a result of the

French Revolution of 1789, Paoli worked to undermine the Revolution on the island, where it was actually popular among native Corsicans.

Despite his role in inspiring countless 18th century revolutionaries, Paoli worked to undermine the French Revolution in Corsica

See the Storming of the Bastille tea towel

After trying to gift Corsica to the British, Paoli was driven into exile for good in 1795.

But his later, rightward turn didn’t undo the global reputation Paoli had forged as a pioneering republican revolutionary during the 1750s and 1760s.

Paoli was hailed by revolutionaries all over the world, including in North America, where the New York Journal described him as simply “the greatest man on earth.”