Cable Street: A Battle against Fascism on London's Streets

Posted by Pete on 4th Oct 2018

When it comes to World War Two, if we think of the 'Home Front' we tend to just imagine the Blitz - German bombers over British cities, RAF bases on endless alert, Clement Attlee down in the public air raid shelters and all that.

Don't get me wrong - it's an important event to remember. The Blitz saw Britain stand up and hold out against Hitler's attempt to blast us into submission.

But if this is all we remember from the Home Front then our gaze needs widening.

An international struggle against fascism comes to London's streets

This is because World War II wasn't just a story in itself, but a chapter - albeit a big and important chapter - in a longer twentieth century struggle against global fascism which began well before 1939.

When we see it like this, new parts of the story come into view. Overseas, for example, the internationalist struggle against Franco in the Spanish Civil War becomes no less relevant than D-Day.

But this email's concerned with something closer to home: the Battle of Cable Street, which took place 82 years ago today, and which - for me at least - remains the greatest moment in the history of London.

To help you get geographically orientated, Cable Street runs through Stepney in Whitechapel. Nowadays you could get there on the DLR, getting off at Shadwell station.

I can't explain how you'd get there back in 1936, but when you arrived you'd have found yourself in the beating heart of Jewish East London.

60,000 of London's 183,000 Jews lived in Stepney in the 1930s. Many of them were recent refugees or children of recent refugees who, like Amy Winehouse's great-grandparents, had sought safety overseas from the Tsars' pogroms in the Russian Empire.

These families came to East London around the turn of the twentieth century, poor and penniless but grateful to be alive.

The all to familiar growth of Fascism

By the 1930s, this working-class Jewish community, with its Irish and English-born neighbours and friends, had become a bastion of socialism in interwar London.

For this reason, and from plain racism, Britain's resident Nazi-in-chief, Oswald Mosley, made East London Jews the number one target of his barbaric new movement, the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

Learning from his idol, Adolf Hitler, the aristocratic Mosley found that scapegoating an ethno-religious minority was a somewhat effective way to con parts of the impoverished working-class into supporting the Far Right.

As such, with the BUF gaining some political ground in neighbouring non-Jewish areas like Bethnal Green, Mosley announced a march of his paramilitary 'Blackshirts' (infamously endorsed by the Daily Mail) through Whitechapel.

Put simply, the fascists were going to try to intimidate innocent Londoners where they lived.

'Try' is the operative word here, however.

East London was going to show Mosley and his thugs the big difference between trying to do something and actually doing it.

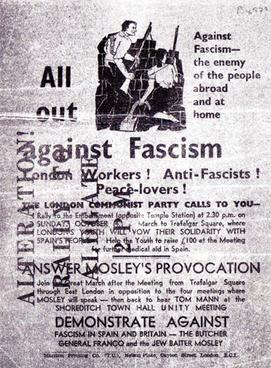

As soon as Mosley announced his march, the Left began to organise against it.

Fascist resistance starts to build

In July, a conference of 86 mostly Leftist organisations came together in East London to establish the 'Jewish People's Council against Fascism and antisemitism' (JPC).

On the 2nd of October, the JPC delivered a 100,000-strong petition of Whitechapel residents to the Liberal Party Home Secretary, John Simon, calling for the march to be banned. He refused, opting instead to provide Mosley with a hefty police escort against anticipated counter-demonstrations.

This was a critical moment in the Cable Street story, if not the story of 1930s Britain.

First, the British state had sided with the fascists. If the JPC wanted to keep Mosley's hooligans out of their neighbourhoods they'd now have to resist the Met Police as well.

Second, John Simon's order meant the more moderate bodies opposed to anti-Semitism, like theLabour Party and the Jewish Board of Deputies, decided to advise people to stay indoors rather than challenge the police.

The JPC thought otherwise - they knew that allowing the fascists to gain control of the streets had been one of the keys to their rise in Italy and Germany. And, considering how many people the JPC went on to mobilise, it would seem East London agreed.

The battle of Cable Street

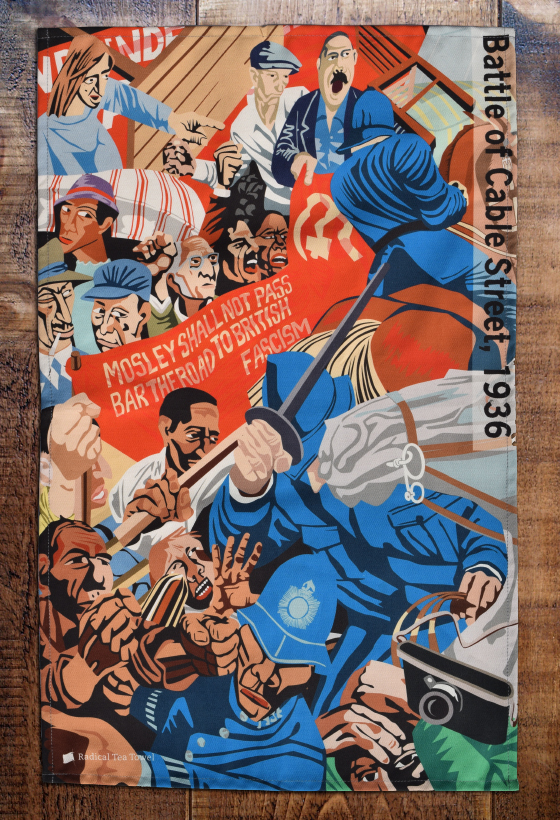

When Mosley arrived on the 4th October with his two thousand Nazis, he was met by a coalition of well over 100,000 British anti-fascists.

It was a multi-ethnic coalition of locals, Communists, the Independent Labour Party (James Keir Hardie's creation), Jewish groups like the Jewish Ex-Servicemen's Association, Irish dockers who remembered how Jewish Whitechapel had supported them in their 1912 strike, and many more.

One resident recalled: "Anybody who was against Mosley was there. It was an amazing conglomeration of people."

Even with its 6,000-strong police escort, the pathetic BUF march didn't stand a chance.

The police - including the entire London mounted division - first tried to force a path at Gardiner's Corner without success.

They then re-routed to Cable Street, where the anti-fascists were waiting with rows of improvised barricades made up of donated household furniture.

One young participant recalled how they were "manned by - god bless 'em - the dockers, Communists, Socialists, Jews. And the cry went up 'They Shall Not Pass' and we made sure that they didn't pass."

And that was that. Mosley and his fascists scurried out of East London, thoroughly beaten.

It's no surprise, then, that Cable Street now stands tall in the People's History of Britain as a heroic struggle of the many against those who wanted to be their masters.

As such, Cable Street has now joined similar events, like the Peasants' Revolt, Peterloo protest, and the Jarrow Crusade, on our radical tea towels!

What a time to be alive.