The 1918 Election Part 2: Constance Markievicz, Irish Independence & Socialism

Posted by Pete on 19th Nov 2018

100 years ago, Britain was in election mode.

It was the first in eight years - the Great War having disrupted the political routine - and it was going to be a big one.

As I wrote last week, it was the first time in British history when any women would be allowed to vote.

Now, usually, something like the enfranchisement of women is the only big story of an election year. And it would have been - if not for an island about 200 miles west of the Pankhursts' Manchester home...

The 1918 Election

When David Lloyd-George decided to announce the vote on 14th November 1918, he was confident of a big victory in Britain because the war had just been 'won'.

But Britain wasn't the only place voting.

Ireland was as well. And the Irish weren't happy.

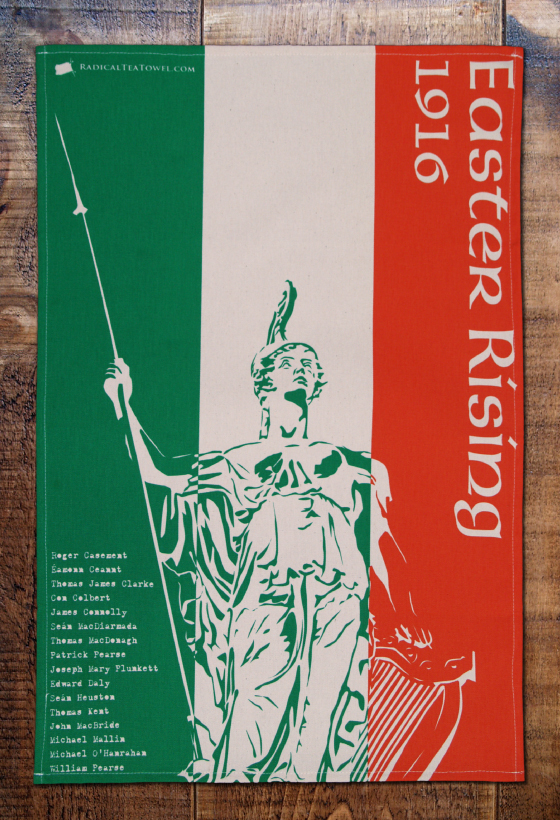

After the Easter Uprising of 1916 was brutally suppressed by the British Army, popular support started to flow from the relatively conservative, pro-devolution Irish Parliamentary Party to republican, pro-independence Sinn Féin.

This flow turned into a flood when in 1918 the British authorities foolishly tried to introduce conscription to Ireland in the closing months of the war.

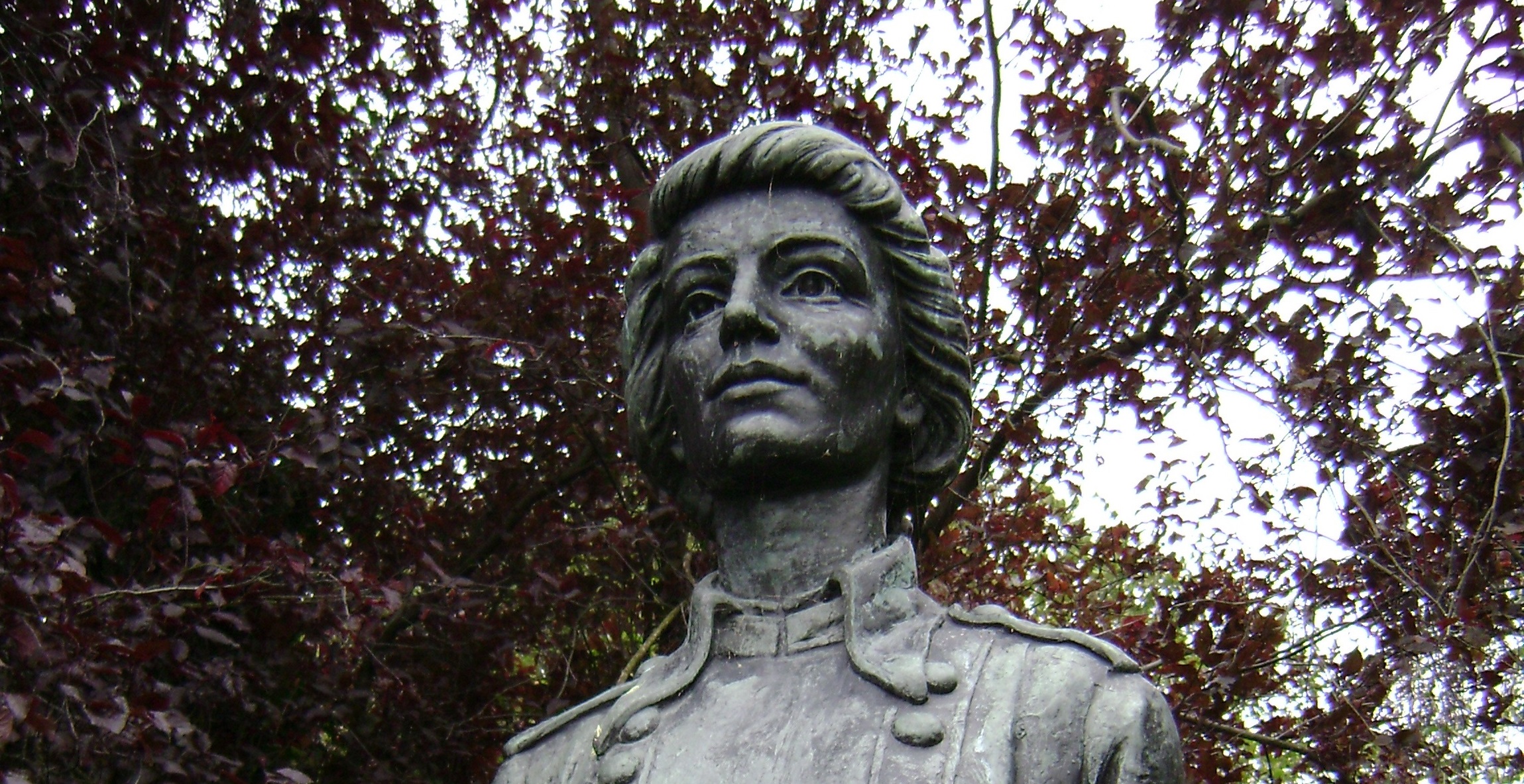

So, when the vote came, tens of thousands of Irish electors put their cross next to Sinn Féin. It won 73 seats - one of them (Dublin St Patrick's) going to Constance Markievicz, who therefore became Britain's first ever female MP.

Suppression of the Irish Independence movement

It was undeniable from this Sinn Féin landslide that Ireland wanted independence.

But Lloyd-George and his cronies weren't democrats, they were imperialists. If Ireland - England's oldest and closest possession - gained independence, they believed the whole Empire would come crashing down.

So, the vote was ignored. More British troops were sent in to support those already there. Britain waged a three-year war of repression against the Irish people and their revolutionary armed forces.

With Winston Churchill at his side as Colonial Secretary, David Lloyd-George's brutality during these years made the bloody response to the Easter Rising look like a picnic. On 21st November 1920, for example, British auxiliaries opened fire on a Gaelic football crowd at Croke Park, murdering fourteen unarmed civilians in cold blood and injuring almost sixty.

It was terrorism in a uniform, but Irish resilience would prove itself stronger.

In 1921, the British government agreed to a ceasefire for talks with the Republicans. Out of these talks came a substantially independent 'Irish Free State' comprising all but the northern six counties of the island.

To have forced the British Empire to concede so much was an achievement for the ages.

But to realise the Free State the Irish movement gave up a lot as well.

Best known was the loss of those six counties in Ulster, where Lloyd-George and the Ulster Unionists wanted to carve out a fiefdom in Ireland still loyal to the Crown.

But something else was misplaced in the maelstrom of the independence struggle - something perhaps more profound than land and border posts.

The impact of socialism on the Irish Independence movement

This was a dream of Ireland independent, but also socialist. It was a dream which had often taken centre stage in the struggle against the Empire.

The four month 'Dublin Lockout' of 1913-14 - when 20,000 Irish workers squared up against their state-backed employers over pay and conditions - was the last great, pre-war agitation in Ireland.

One of the Lockout's leaders, James Connolly, was a charismatic figure and theorist of world socialism as well as the Irish national movement. An acquaintance of Lenin, he once famously declared on behalf of the working-class: "our demands most moderate are, we only want the Earth."

A few years later, with the War of Independence raging across Ireland, striking trade unionists declared a 'Soviet' in the town of Limerick.

Far from the state repression found in the USSR, the 'Limerick Soviet' (before its all-too-quick dissolution) was what a 'soviet' was supposed to be - good, democratic government by the working people. There was no crime or looting, food prices were fixed, and religious toleration reigned.

But the Irish socialism seen in these acts of resistance wasn't allowed to shape independence and (for once) this was not all the fault of the British.

Much of the Sinn Féin leadership became bound up with elements hostile to a socially progressive agenda. Irish landowners were supported against tenant farmers, and the religiously sectarian strain of Irish nationalism - best represented by Eamon de Valera - tacked far too close to conservative parts of the Catholic Church.

Against these forces, socialist republicanism was unable to gain much ground and so, in a cruel way, the Ireland which came out of independence was hardly less reactionary than any other 20th century state.

As James Connolly forecast way back in 1897:

"If you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the Socialist Republic your efforts would be vain."

'Vain', I think, goes too far - the victory of the Irish over Britain's Empire in 1921 remains a valued part of the heritage of anti-colonialist thought and practise.

To point out the flaws in this victory isn't to deny that.

But it keeps us from forgetting the past hopes that were lost in the struggle, and in doing so might point us towards what needs to be recovered by radical politics in the present.