The 1918 Election Part 3: John Maclean, Labour and the Sacrifice of Radicalism

Posted by Pete on 14th Dec 2018

This is the third part of our series on the 1918 General Election. As well as for women and Ireland, the election was a landmark for the Labour Party. But some true radicals such as Scottish politician John Maclean have been forgotten. Until now.

A century ago, Britons went to the polls.

More often than not, the 1918 General Election is remembered either as the first British poll in which women took part or the one when Ireland voted overwhelmingly for Sinn Fein, starting the road to her eventual independence from Britain.

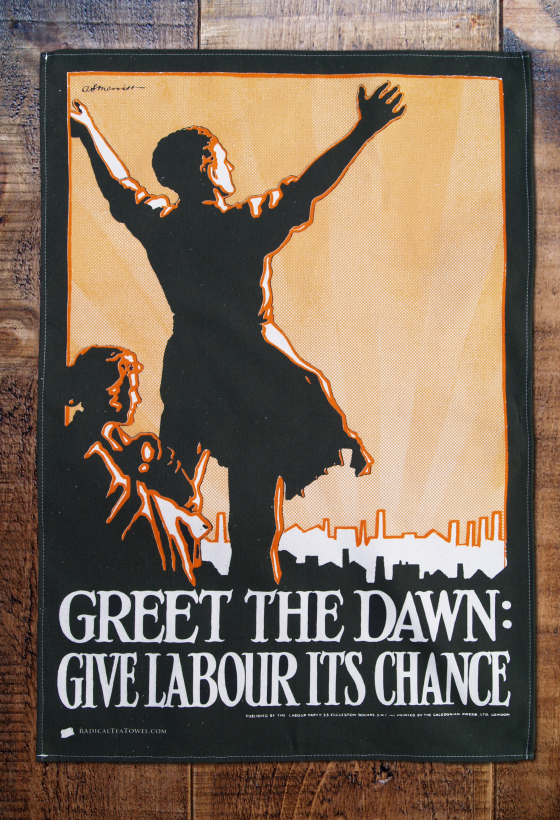

But it was also a big event in the history of the Labour Party - the moment when it became one of the two biggest forces in British electoral politics, never to look back.

Labour Party Successes in 1918

The Party recorded 20.8% of the vote, taking 57 seats in Parliament (still a disproportionately small number - blame first-past-the-post!).

It was the beginning of an upward journey, with Labour taking office for the first time in 1923.

But rather than the party as a whole, I'd like to take a few minutes to look at just one of Labour's 1918 candidates - and an unsuccessful one at that.

John Maclean stood in the working class Gorbals area of Glasgow, narrowly losing out to the incumbent who'd recently defected from Labour to David Lloyd-George's Liberals.

Like many contemporary Labour politicians, Maclean was Scottish and working class (born to rural immigrant parents from the Highlands). The parallels with James Keir Hardie are obvious.

But John Maclean wasn't a 'typical Labour candidate'.

For one thing - like many of our Radical Tea Towel characters - he was from the Left tradition of the British labour movement. He joined the Social Democratic Federation - a Marxist group set up by William Morris, Eleanor Marx, and others - and created its branch in his Glaswegian hometown of Pollokshaws.

But what marked Maclean out most was his courage.

Maclean's steadfast opposition to imperialism

It was a very particular kind of courage which has always been demanded of (but rarely given by) socialists in Western Europe.

As if ideas can have a 'nationality', conservatives have often labelled socialism 'foreign' so they can attack socialists as 'aliens' and 'infiltrators'.

Under this kind of pressure, many Leftists have given up their principles, to win votes or escape intimidation. They abandon their internationalism and restrict their programmes to something the conservatives can bear - limited social reforms combined with a nationalist foreign policy.

But a special few, who also earned places on some of our designs, refused that path.

Sylvia Pankhurst and Ellen Wilkinson; Aneurin Bevan when he broke with the Labour Right in the 1930s to advocate an alliance with the USSR against international fascism. And those who backed aid for the Spanish Republicans.

John Maclean belongs to this prestigious group.

He denounced World War I as the imperialist adventure it was, while Labour men like Arthur Henderson fell in behind the government.

Maclean showed constant, vocal solidarity for the Irish struggle against British imperialism at a time when too many British socialists remained silent. During a visit in 1907, for example, he became a close comrade of Ireland's socialist leader, Jim Larkin.

And this support for the Irish was a manifestation of Maclean's wider anti-imperialism. He once famously declared:

"I hold that the British empire is the greatest menace to the human race... the best interest of humanity can therefore be served by the break-up of the British Empire." - John Maclean

This at a time when plenty of Labour politicians were fully complicit in Edwardian imperialism.

Maclean was a true radical of 1918

The abuse and persecution Maclean received from the state for these principles goes a long way to explain why so many socialists were afraid to join him in his radical internationalism.

On 15th April 1918, Maclean was arrested for 'sedition' (the tyrant's favourite accusation) by the Lloyd-George Liberal-led government. He was sent to Peterhead prison, near Aberdeen, where, like the Suffragettes, he was subjected to force-feeding (i.e. torture) because he was striking against the injustice of his imprisonment.

Because of the health damage inflicted on him at Peterhead, Maclean was left very weak on release. In November 1923, at the age of just 44, he collapsed while giving a speech - dying soon after of pneumonia.

I'd say that John Maclean was killed by the British state because he was an internationalist socialist.

Immensely popular among the Scottish working class, his funeral was the biggest public event in Glaswegian history.

But it wasn't the John Macleans of the labour movement who led the Labour Party into the 1918 election. It was those who did too much of what power wanted - abandoned the Irish rebels, left imperialism unopposed, and stayed silent as Britain intervened on behalf of the Russian Whites against the Reds.

So, while Labour's 1918 result was an important landmark in the electoral history of the party, it's worth taking a closer look at the fringes. It's there that we find the true radicals.

More than a single poll, the political example set by a rebel like John Maclean is of continuing use to the struggle for justice, at home and for all humanity.

"I am a socialist, and have been fighting and will fight for an absolute reconstruction of society for the benefit of all. I am proud of my conduct." - John Maclean