We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

Alexandre Pétion: The Man of Three Revolutions

Haiti's first President realised that for his country to be free, slavery would have to be abolished everywhere

For a long time the Haitian Revolution was completely forgotten.

The work of radical historians, like C. L. R. James’ Black Jacobins (1938), has begun to slowly change things.

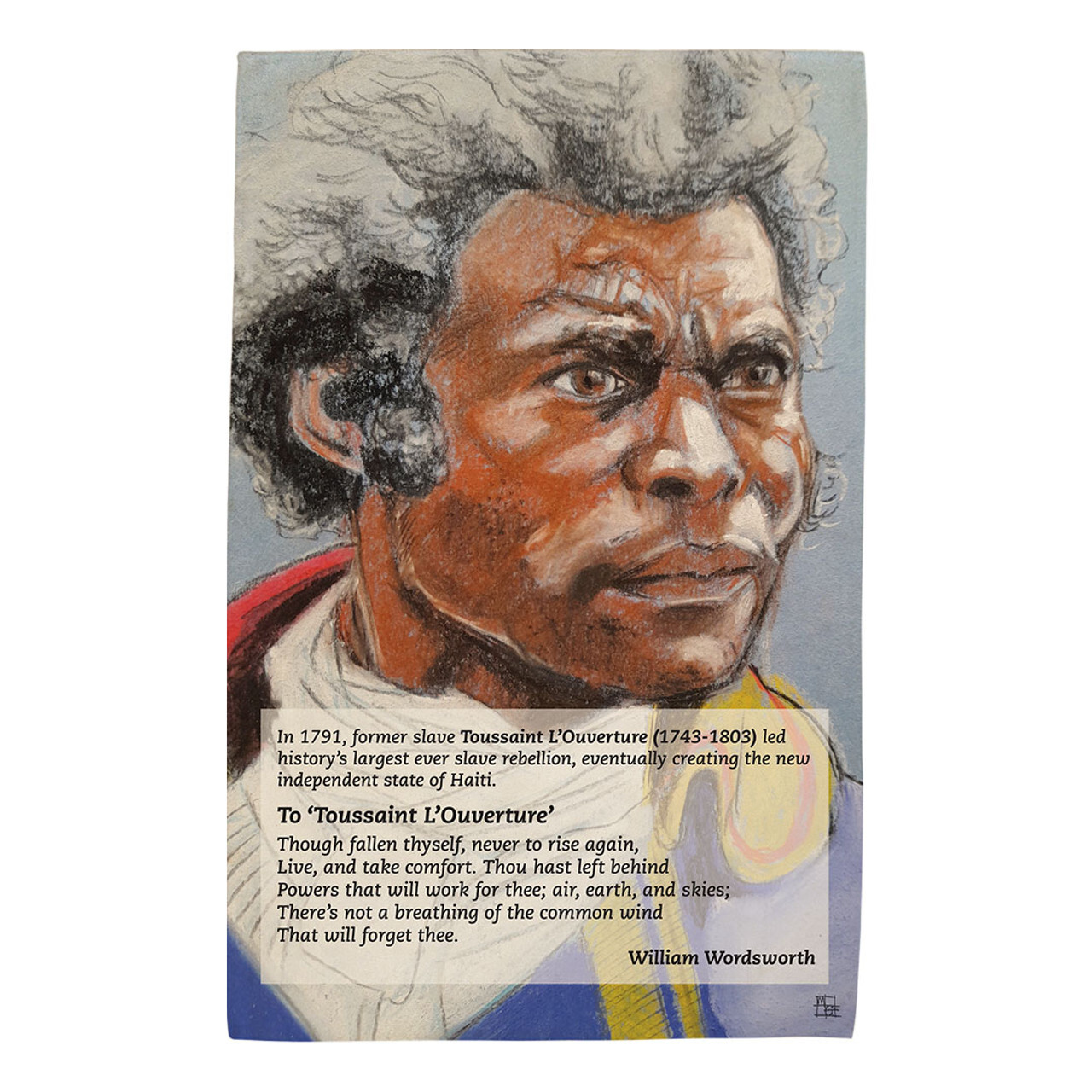

But even now, insofar as people have heard of the Haitian Revolution, they tend to think of one man: Toussaint L'Ouverture.

But Toussaint wasn’t the only ‘Black Jacobin.’

In some ways more radical, Alexandre Sabès Pétion was born on this day in 1770.

When people think of black slave rebellions, they tend to think of Haiti's Toussaint L'Ouverture

See the Toussaint L'Ouverture tea towel

Pétion was born in Port-au-Prince, the French capital of Saint Domingue (the future Haiti).

Unlike Toussaint, Pétion was not born into slavery.

In the system of racial classification imposed on the black inhabitants of Saint Domingue by the French empire, Pétion was a ‘quadroon’ – ¼ African descent on his mum, Ursula’s side.

Pétion’s father, Pascal, was a rich, white Frenchman.

So, Alexandre Pétion grew up as part of the small class of wealthy and legally free gens de couleur, while the vast majority of black people in Saint Domingue were brutally enslaved on the plantations.

In 1788, Pétion was sent across the Atlantic to Paris, to study at the Royal Military Academy there.

But change was afoot in France...

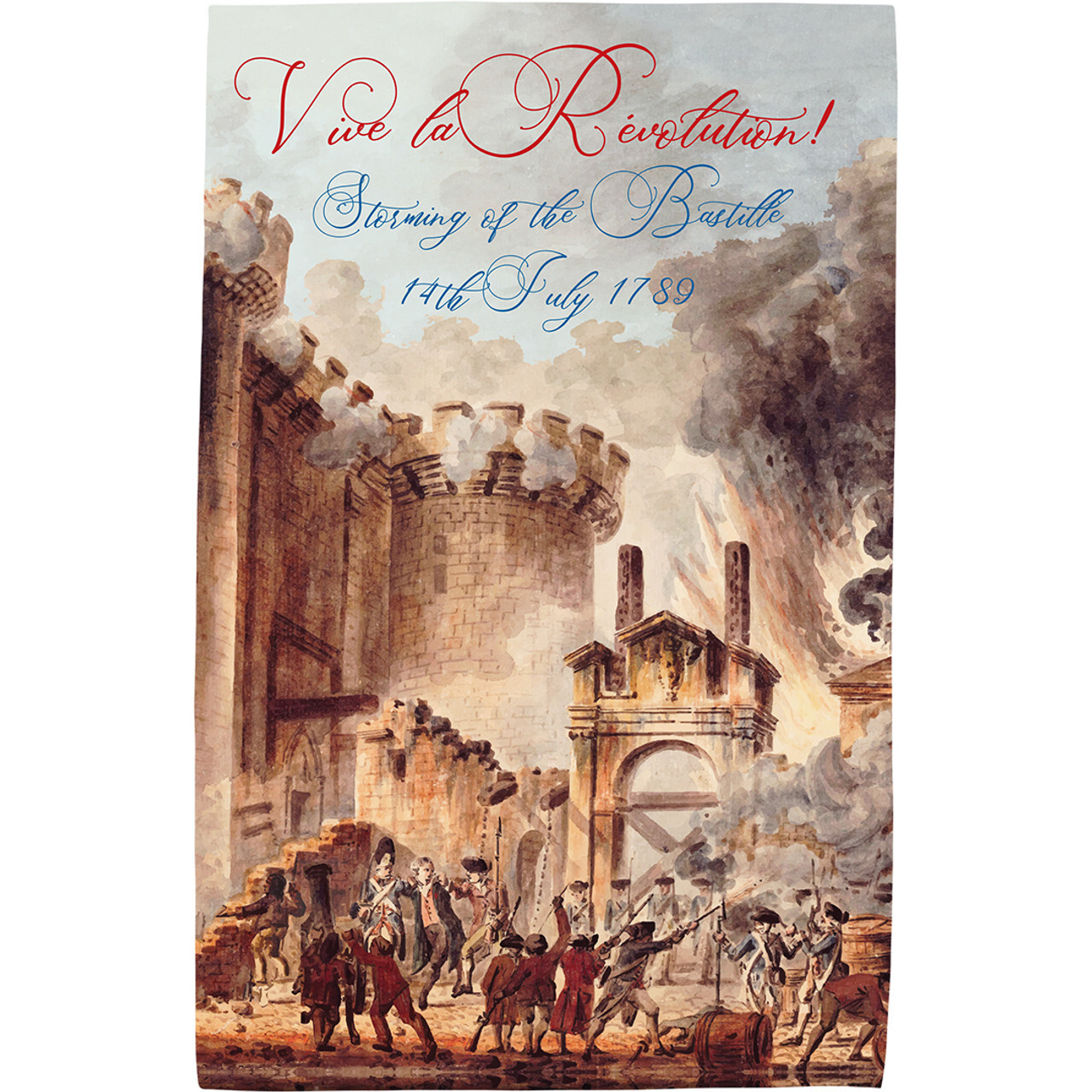

The French Revolution of 1789 unleashed a wave of political demands throughout the French empire.

In Saint Domingue, the free people of colour like Pétion mobilised.

As a class, this group (initially) had no major problem with black slavery – many were slaveholders themselves.

Rather than abolition, then, free black subjects in Saint Domingue began the French Revolution by demanding equal civic and political rights for all free Frenchmen, not only free whites.

But the enslaved black majority in Saint Domingue had no intention of just watching on from the sidelines.

The French Revolution emboldened those seeking freedom everywhere, including slaves

See the Storming of the Bastille tea towel

In 1791, a massive slave rebellion was launched to take advantage of the political opportunities created by the French Revolution.

Soon led by Toussaint Louverture, a former slave from the northern town of Cap-Français, this movement became the only successful slave rebellion in history.

In 1793, the French republican authorities in Saint Domingue agreed to the slaves’ demand for abolition.

Alexandre Pétion was serving as an officer in the French army at this point, and he fully backed abolition.

With Toussaint and other black leaders, Pétion helped fight off several British and Spanish attempts to conquer Saint Domingue, overthrow the revolution, and restore slavery.

But all wasn’t well in the revolutionary camp.

As Toussaint gained increasing autonomy from France, many of his fellow black officers became alienated from him.

This was especially true of freeborn and often lighter-skinned republicans of Pétion’s class.

Tensions came to a head in 1799, when Pétion participated in an unsuccessful rebellion against Toussaint.

After the rebels lost, they had to flee into exile in France.

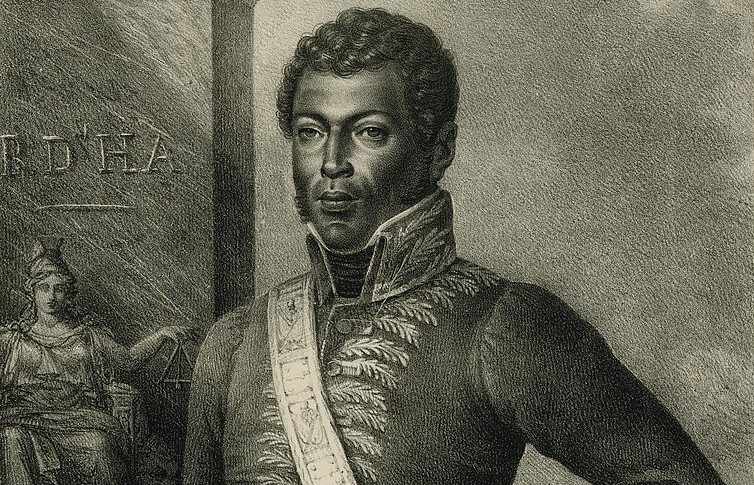

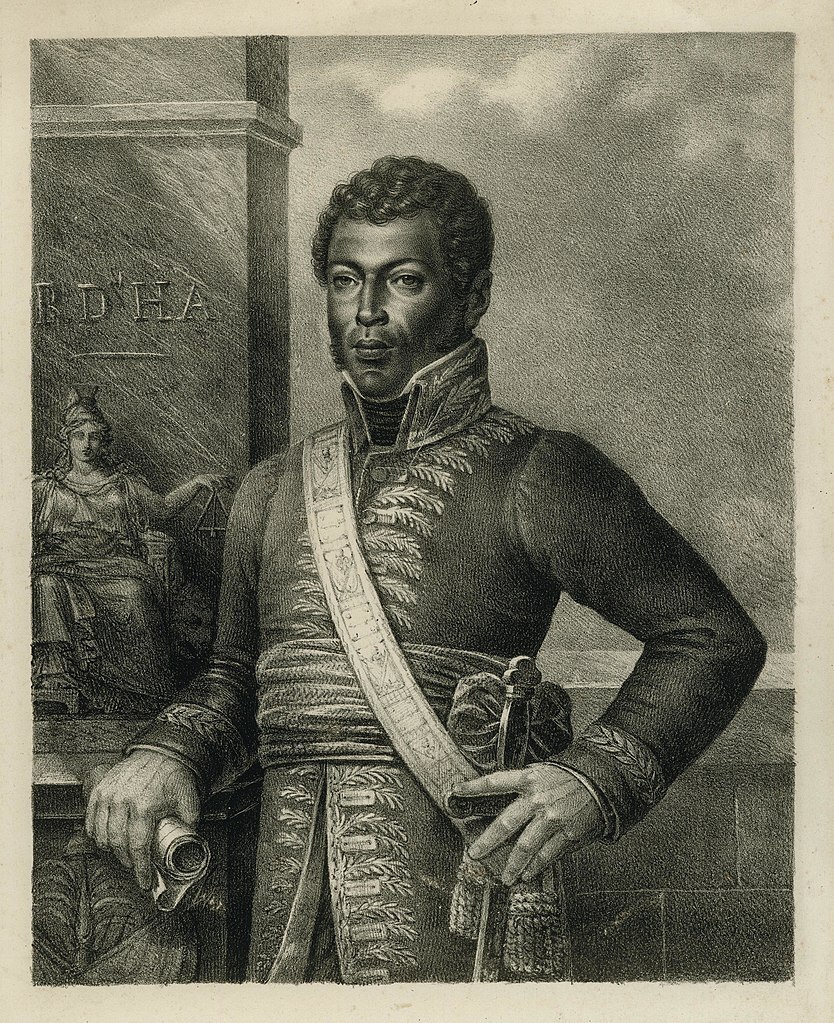

Alexandre Pétion, first President of the Republic of Haiti, in the early 19th century

But the French government wanted to take back control of Saint Domingue from Toussaint, too.

Pétion and his comrades joined the French – “my enemy’s enemy...” – returning to Saint Domingue in 1802 in the army sent by Napoleon.

Toussaint was quickly defeated and deported to France, where he died soon after.

But Napoleon hadn’t won.

The defection of black soldiers like Pétion and Toussaint’s old lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, had been crucial to the French victory.

Now, in late-1802, these black officers realised that Napoleon didn’t just want to remove Toussaint – the French government intended to restore slavery in Saint Domingue, too.

So, Dessalines launched a new rebellion against the French and, in October 1802, Pétion joined him.

Despite brutal French violence, the black republicans won back control of the island by the end of 1803 and on New Year’s Day, Dessalines declared Haitian independence.

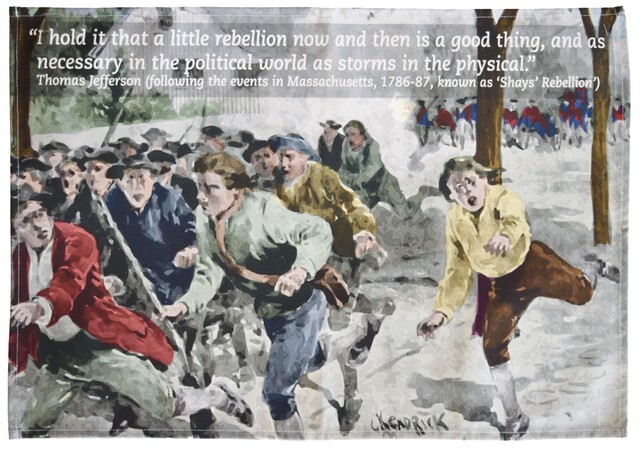

A bit of rebellion is normally a good thing, according to Thomas Jefferson - especially in the late 18th century

See the Shays' Rebellion tea towel

Pétion emerged as a key progressive figure in independent Haiti during the 1800s and 1810s.

He successfully resisted attempts by Dessalines and then Henri Christophe to turn Haiti from a republic into a monarchy, like Napoleon had done in France.

Pétion also rejected Toussaint’s policy of forced labour, designed to restore the plantation economy against the will of Haitian workers.

Instead, Pétion divided up large estates and redistributed them to Haitian peasants.

And Pétion dropped Toussaint’s refusal to export the Haitian Revolution abroad, too.

Pétion appreciated that the only world in which a free Haiti could be secure was one without slavery anywhere.

So, he offered liberation and asylum to any enslaved person who could escape and reach Haitian territory.

And Pétion also gave decisive military aid to the Venezuelan revolutionary leader, Simón Bolívar, in return for Bolívar’s promise to abolish slavery in liberated Spanish America.

When he died in 1818, then, Pétion had played a pivotal role in not one but three revolutions: France, Latin America, and Haiti.

The Haitian Revolution, then, had a cast of many characters, not just Toussaint.

See Freedom Fighters & Rebels tea towels