And After the Farewell: The Story of the Carnation Revolution

Posted by Pete on 25th Apr 2022

How a song led to the overthrow of Portugal's fascist regime...

At 10:55am on 24 April 1974, Paulo de Carvalho's song “E Depois do Adeus” was played on Lisbon radio.

The song - translated as “And After the Farewell” - was Portugal’s entry to that year’s Eurovision Song Contest.

On any other day, this would’ve been a completely unremarkable event.

But on that day the song was more than just a song: it was a secret signal, used by the left-wing Movimiento das Forças Armadas (MFA) to mark the beginning of a military coup against Portugal’s fifty year-old fascist dictatorship.

The 1970s was a time of great global upheaval: in November 1970, the socialist Salvador Allende was elected President of Chile

Click to view our Salvador Allende tea towel

Way back in 1926, a far-right coup had seized control of Portugal. The regime called itself the ‘Estado Novo’ (‘New State’), headed by Prime Minister António de Oliveira Salazar, who would rule until 1968.

An ally of Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War, Salazar’s Portugal was conspicuously ‘neutral’ during the Second World War, cheering on the Nazi invasion of the USSR and only tilting away from the Axis when they began to lose.

After WW2, the Western democracies happily forgot Salazar’s fascist sympathies during the 1930s and 1940s.

In fact, Salazar’s anti-communist credentials – including decades of persecuting, torturing and executing leftist dissidents in Portugal – chimed well with the Red Scare that swept across the West in the 1940s.

The British and American governments had no problem with the right-wing dictatorship: Portugal was accepted as a founding member of NATO in 1949.

So, it would be down to the Portuguese people to throw out the Estado Novo regime.

While the international Left had supported the republican cause in Spain, Portugal had been an unofficial ally of Franco's forces

Click to view our Help Spain tea towel

In 1968, Salazar was incapacitated by a stroke. His replacement, Marcello Caetano, inherited an angry and exhausted country.

Portugal had long been struggling to keep hold of its still vast colonial empire in sub-Saharan Africa. From Mozambique in the east to Angola and Guinea-Bissau in the west, anticolonial fighters like Amílcar Cabral were rising up against the fascist empire.

These rebels enjoyed growing support from left-wing protestors in Portugal itself, including parts of the army.

Seeing that Caetano’s government was weak, progressive elements in the military formed the MFA and launched a coup.

But a military coup built around generals – generals who had served the Estado Novo for a long time – would not be enough to support a transition from right-wing dictatorship to progressive democracy.

What guarantee was there that the coup would not just replace Caetano with another dictator?

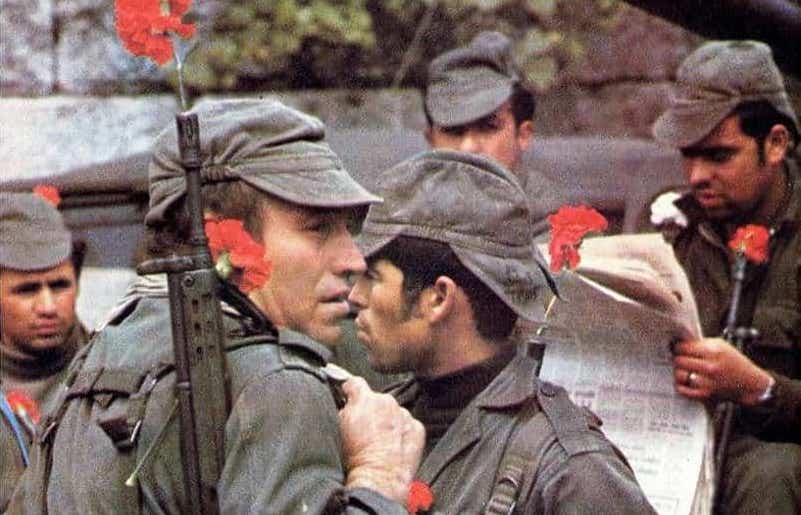

A crowd celebrates the revolution in Lisbon on 25th April, 1974 (Source: Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril)

Thankfully, mass action by the Portuguese people meant that democracy prevailed.

Despite army radio asking civilians to stay home while it neutralised Estado Novo loyalists, the people of Portugal came out in their thousands.

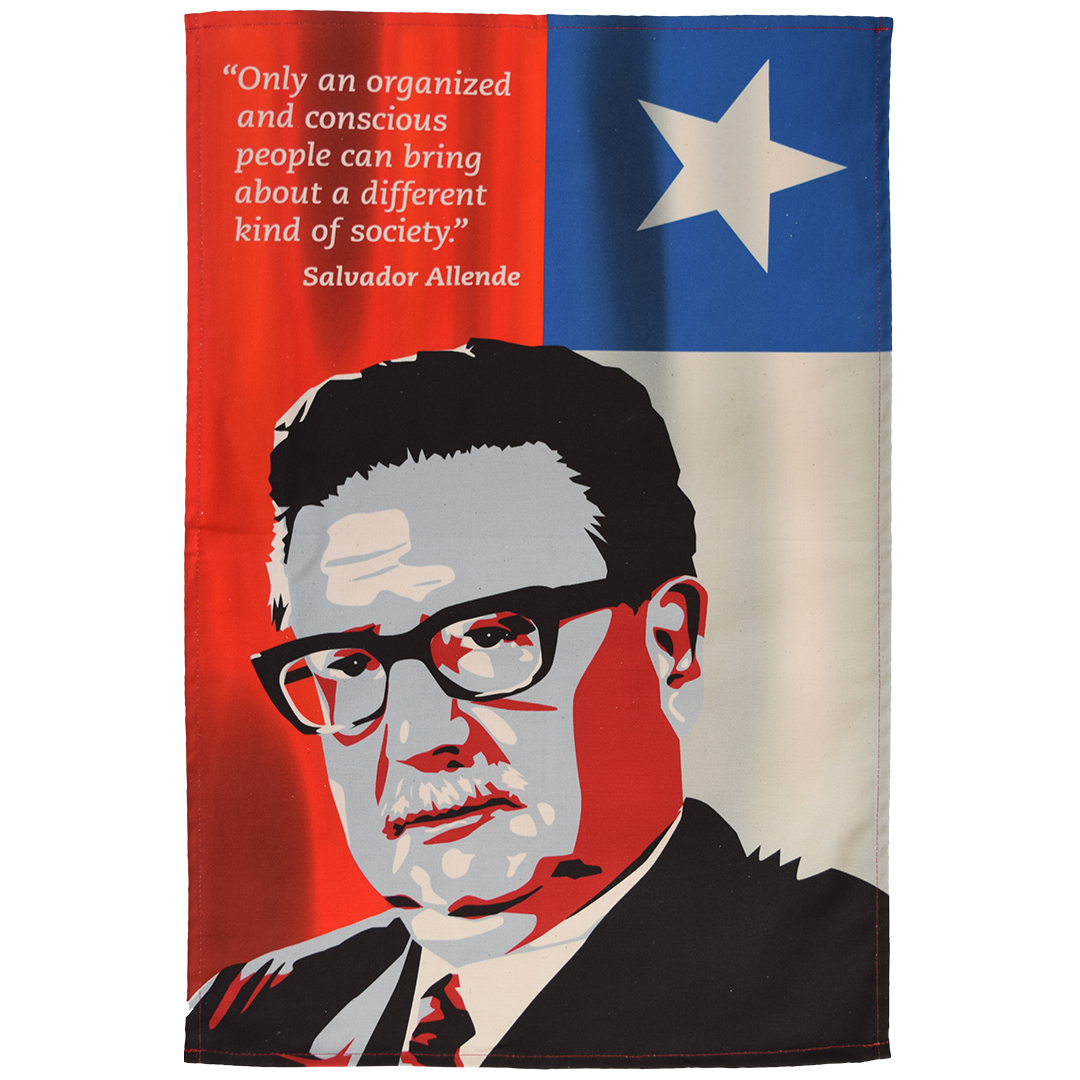

Insurrectionary troops were embraced by the long-oppressed people of Portugal. The streets of the capital were flooded with jubilant soldiers and citizens.

One hub was the Lisbon flower market, which was full of in-season carnations. The people began to hand these out to the troops, decorating their tanks and rifles with the flower – hence the event became known as the Carnation Revolution.

In all, it was a strikingly peaceful revolution. Having lost the bulk of the army, the Estado Novo had little option but to capitulate.

Four civilian protesters were shot dead by regime loyalists, but their killers were soon arrested by the MFA.

In the aftermath, democracy was gradually consolidated in Portugal. In 1976, the country’s first constitutional government in fifty years was elected under the socialist leader Mário Soares.

The new regime accepted that Portugal’s empire had been defeated by anticolonial struggles. From 1974 to 1975, the last Portuguese troops were withdrawn from the colonies in Asia and Africa.

And just as Salazar’s support had helped to bolster fascist Spain, the fall of the Estado Novo was a key factor in making sure that, when Franco died in 1975, his dictatorship would fall with him.

Too little remembered outside Portugal, the Carnation Revolution was the last great popular uprising in Western European history – an event well worth celebrating.

And to think, it all started with a song on the radio!