Floating Republic: The Nore Mutiny of 1797

Posted by Pete on 26th Jun 2023

In 1797, Royal Navy sailors launched a mutiny on the Thames

In May 1797, a republic floated down the River Thames. Its provinces were ships, and its citizens were sailors.

And these weren’t just any sailors. They were Royal Navy mutineers.

The British empire had been at war with France since the

French Revolution. At home, this war involved the violent state repression of progressive activists in Britain, including Thomas Paine.

Thomas Paine was one of many radical pamphleteers targeted by the British government for his support of the French Revolution

Click to view our Thomas Paine tea towel

Abroad, British forces were fighting France and its allies on several fronts, all over the world. And everywhere, the Royal Navy was key.

Britain’s sea power could strike anywhere, and it was the only thing stopping a French invasion across the Channel.

So, you’d think the government would make sure to take care of its sailors…

But no. Royal Navy sailors were a downtrodden class in late eighteenth-century Britain.

Many had been kidnapped by government thugs and forced into service, where they were constantly abused by snobbish, aristocratic officers.

Seamen’s real pay was falling, food supplies aboard ship were terrible, and there wasn’t enough shore leave.

So what did they do? They mutinied.

The Storming of the Bastille in 1789 became a symbol of the radical struggle against tyranny across Europe

Click to view our Storming of the Bastille tea towel

In April 1797, the sailors of the Channel Fleet, anchored at Spithead, seized control of their ships.

They demanded a pay rise, better food supplies, more shore leave, and compensation for injuries and sickness.

The mutiny soon spread to ships in nearby Portsmouth, with unpopular officers forced to shore.

And the government quickly gave in.

When push came to shove, British power relied on the common sailors of the Royal Navy. The mutineers had leverage.

Mutiny leaders were pardoned, pay rises granted, and better food supplies guaranteed.

News of the victorious mutiny at Spithead quickly spread through the Navy. It was inspirational for rank-and-file sailors.

On 12 May 1797, the crew of HMS

Sandwich, then stationed at the Nore in the Thames Estuary, seized control of the ship.

Nearby crews followed suit, and the mutineers took control of the local area.

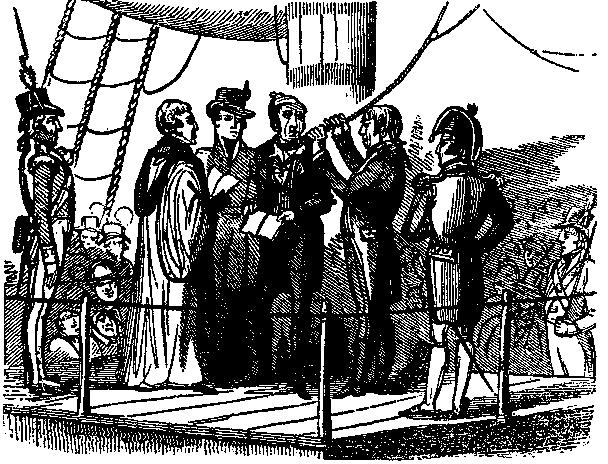

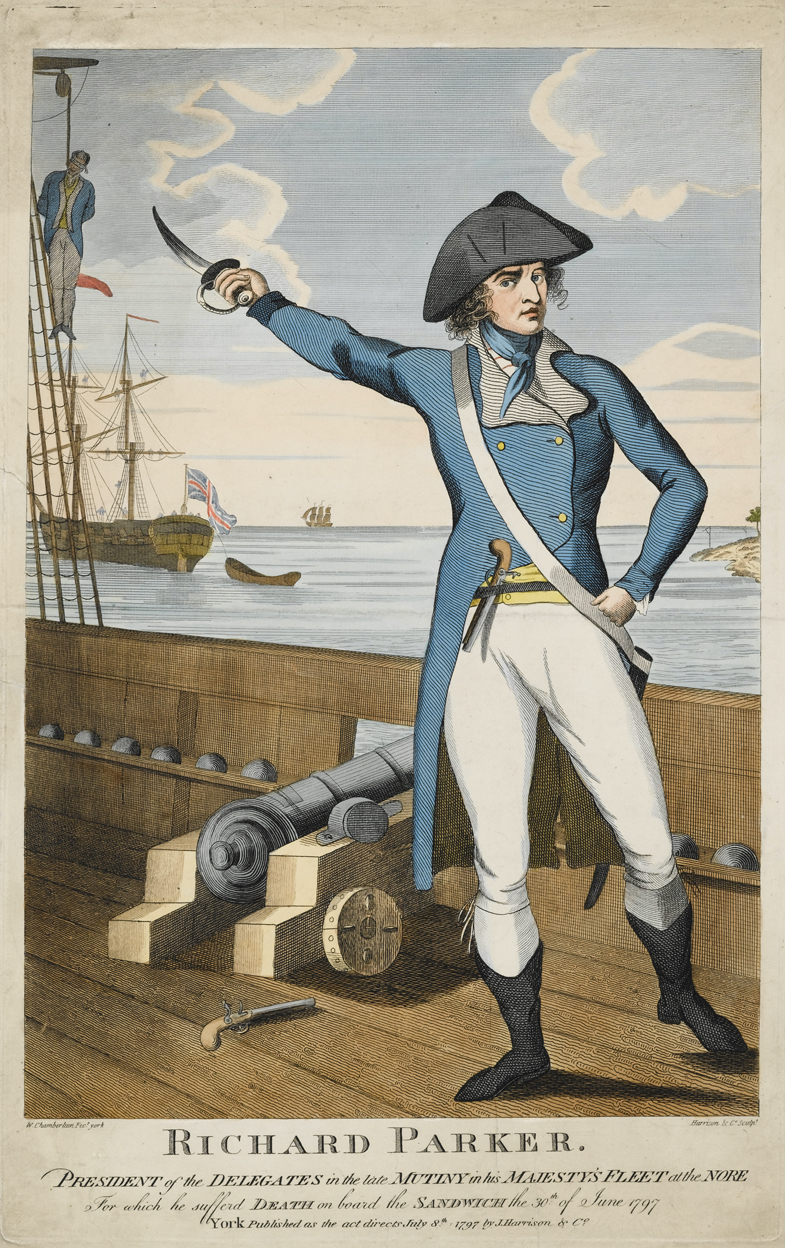

Richard Parker was the leader of the mutiny at the Nore

As at Spithead, the mutiny at the Nore was a democratic project. Each ship elected its own delegate, to help sort out a common bargaining position.

Richard Parker, a seaman on HMS

Hound, who had a record of standing up to cruel officers, was elected ‘President of the Delegates of the Fleet’.

On 20 May, the Nore mutineers sent their demands to the Admiralty, including increased pay and an end to corporal punishment aboard ships.

The government, terrified that it was now losing control of the entire Navy, decided to stand firm. They would offer nothing more than had been conceded at Spithead.

And a fleet of loyal ships was hastily put together in London, to fight it out with the mutineers.

This hardline response only radicalised the political movement developing at the Nore.

The Delegates of the Fleet now also demanded immediate peace with revolutionary France, and new parliamentary elections in England.

But the government didn’t blink. The loyalist fleet began to move downriver towards the Nore.

Outgunned, some ships began to abandon the mutiny, and when the leaders tried to order an evacuation to France, the sailors refused to go.

The Nore mutineers were harshly punished. Richard Parker was hanged for treason and piracy, along with 28 others.

There were imprisonments, floggings, and some men were deported to the British penal colony in Australia.

But even in defeat, the floating republic at the Nore remains a remarkable – if little-known – chapter in the radical history of the British isles.