Queen Bessie: The Woman who made Black Liberation Airborne

Posted by Pete on 28th Apr 2025

"Because of Bessie Coleman we have overcome that which was worse than racial barriers. We have overcome the barriers within ourselves and dared to dream."

In 1920s America, the airplane was the future.

After the destruction of World War I, the new technology of human flight promised a brighter future.

But as U.S. society moved into the skies above North America, it brought its social injustice with it.

No black, indigenous, or women citizens were allowed to train in the new flight schools opening around the country.

American aviation was to be a white man’s world, belonging exclusively to people like the Nazi sympathiser and white supremacist, Charles Lindbergh.

If unopposed, the new era of flight would see Jim Crow take to the skies.

But it was opposed.

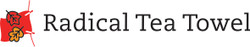

Bessie Coleman is one of 12 women pioneers to feature on our new tea towel

See the Women Pioneers tea towel

While aviation didn’t develop outside the inequality of U.S. society, it wasn’t ignored by U.S. liberation movements, either.

The Afro-Indigenous Texan, Bessie Coleman, made sure of that.

Elizabeth Coleman couldn’t have been further from Lindbergh, in social background or political virtue.

She was born in Texas in 1892 to a working-class family of black sharecroppers. Her dad, George, had Cherokee or Choctaw heritage, too.

As a child, ‘Bessie’ walked 4 miles a day to attend her segregated school in Waxahachie, where she was an excellent student. She also had to work on the cotton harvest, too.

Aged 18, Bessie saved enough to enrol for one term at Langston University in Oklahoma before the money ran out.

A few years later, in 1915, she escaped the rural Jim Crow South for Chicago.

It was here that Coleman began to hear about flying from U.S. pilots home from the war in Europe.

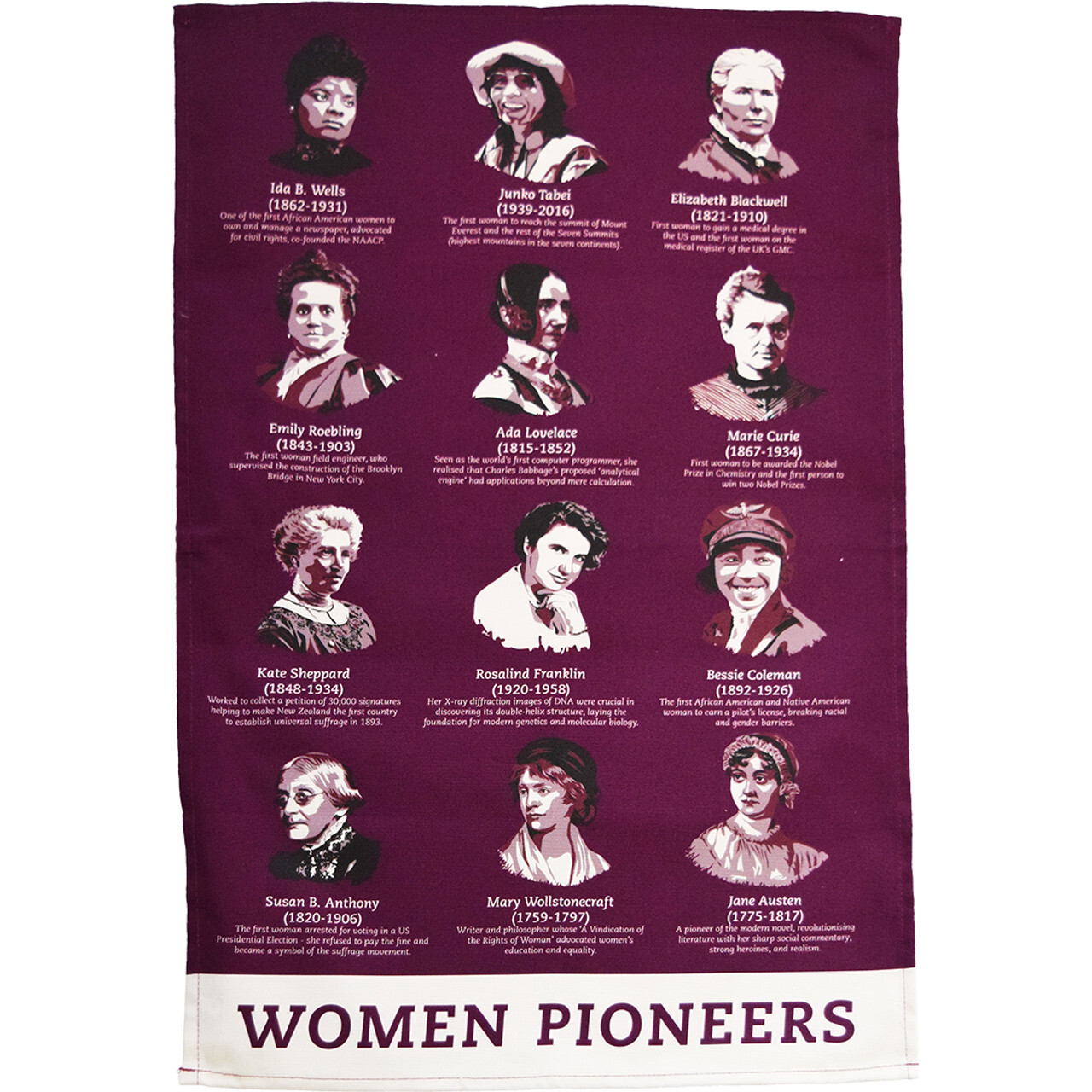

Chicago's radical reputation made it the best place for Bessie Coleman to seek help in realising her ambitions

See the Anarchists of Chicago tea towel

Determined to become an aviator herself, Coleman took on a second job to save up for flight school.

It was a self-consciously political mission.

"The air is the only place free from prejudices. I knew we had no aviators, neither men nor women, and I knew the race needed to be represented along this most important line, so I thought it my duty to risk my life to learn aviation."

Coleman understood how aviation now symbolised modernity in America. If people of colour were excluded from this new field, it would only help white supremacists to slander them as ‘backward’.

But because of white supremacy, there was no chance Coleman would be able to train as a pilot in the United States.

Thankfully, Chicago was a radical town.

Even after the reactionary crackdown of the late 1910s, there was still a progressive network to help Coleman fly.

Robert S. Abbott, the black editor of the anti-Jim Crow, pro-civil rights newspaper the Chicago Defender, helped Coleman raise money for pilot training in France.

In November 1920, Coleman travelled to Paris.

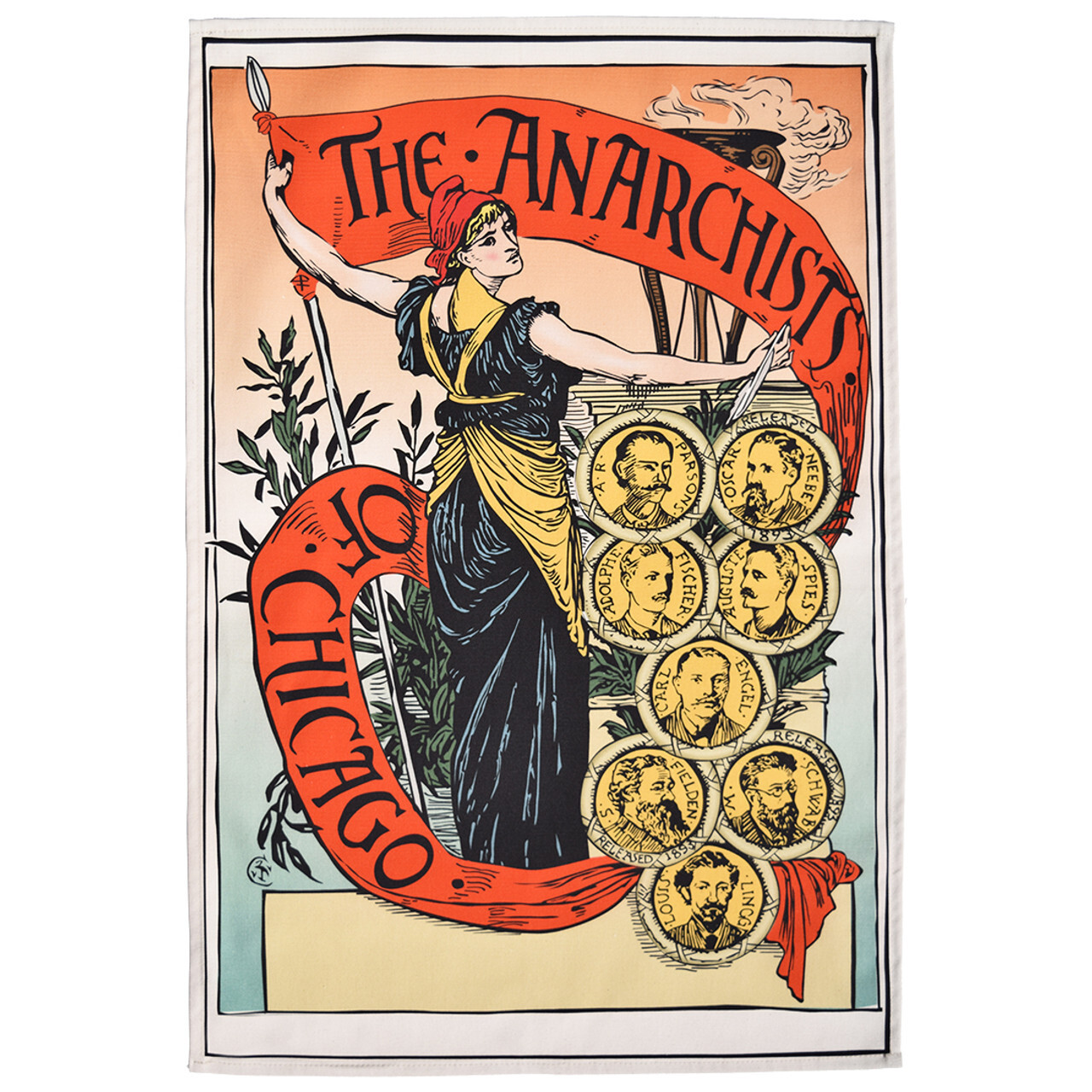

Not for the last time – James Baldwin would make the same journey – an African American who outmanoeuvred U.S. racism via France.

Like Bessie Coleman before him, James Baldwin travelled to France to escape the strictures of US racism

See the James Baldwin tea towel

On 15 June 1921, Coleman completed her training and received her pilot’s license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI).

This made her the first black or indigenous American, and the first American woman, to receive a pilot’s license.

It also made her the first American full-stop to receive a license directly from the prestigious FAI.

Coleman had her pilot’s license – now she was going to use it.

The only civilian career for a pilot in the 1920s was as a ‘barnstormer’ – a stunt flier at airshows. And ‘Queen Bessie’ was soon America’s greatest.

Coleman was an expert daredevil. She performed aerial acrobatics – figure eights, loops, near-ground dips and spins – at shows across the country.

And Coleman’s flying was part and parcel of her commitment to racial justice, too.

Her first shows were sponsored by the Chicago Defender, celebrating the return of black veterans of WW1 who’d defied racist stereotypes to serve as frontline infantrymen in France.

Coleman also boycotted any segregated airshows, and she regularly spoke against white racism during her tours of the U.S.

But Coleman’s flying career – and her heroic life – were cut short.

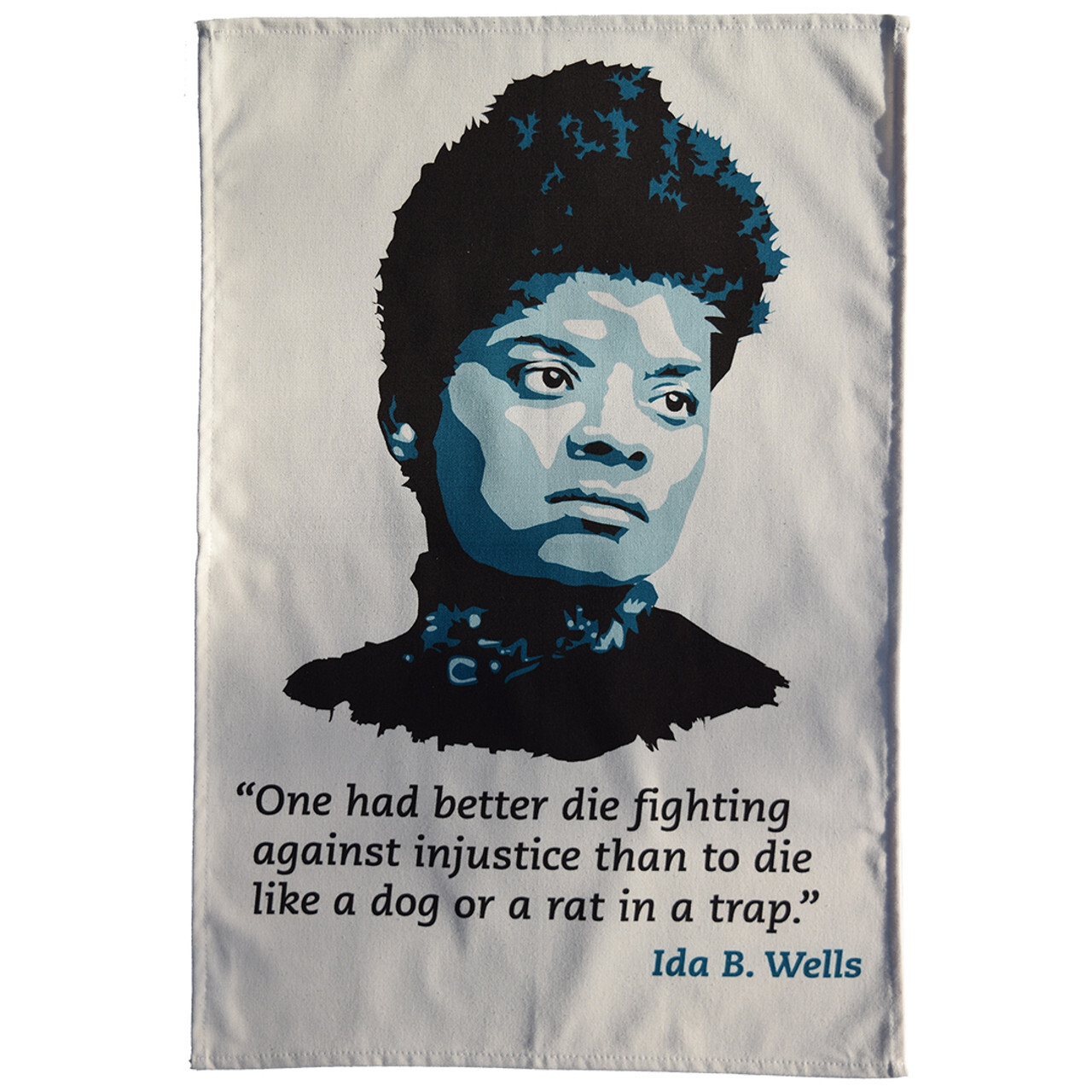

Journalist Ida B Wells joined thousands in Chicago to mourn heroine Bessie Coleman

Whereas a white man with her talent would’ve been paid more than enough to use only the best aircraft, Coleman had to make do with dangerously poor-quality flying machines.

And it was in one of these, on 30 April 1926, that Coleman and her mechanic, William Willis, crashed and died in Florida.

Coleman, an icon of black liberation, was mourned by 10,000 people in Chicago, led by the black feminist, Ida B. Wells.

Bessie Coleman had done for the 1920s what people like Frederick Douglass did in the Civil War-era: she ridiculed anti-black prejudice by the force of her own sheer excellence.

And Coleman’s achievement created a new, radical tradition of black aviation in the U.S., from John Robinson, ‘The Brown Condor,’ who joined the Ethiopian air force to oppose Mussolini’s 1935 invasion, to the civil rights activist Willa Beatrice Brown, the first African American woman to run for Congress.

Queen Bessie truly made black liberation airborne.