We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

Spartacus and the Original Slave Rebellion

Spartacus, a gladiator during the time of the Roman Empire, rose up against the elites and inspired slave rebellions centuries later

Above: the 'Death of Spartacus' by Hermann Vogel (1882)

This is the furthest back in time we’ve ever gone.

Spartacus (circa. 103-71 BC) was an enslaved Thracian from the Balkans.

In 73 BC he led a slave rebellion at the heart of the Roman Empire which, two millennia later, continues to inspire progressive politics.

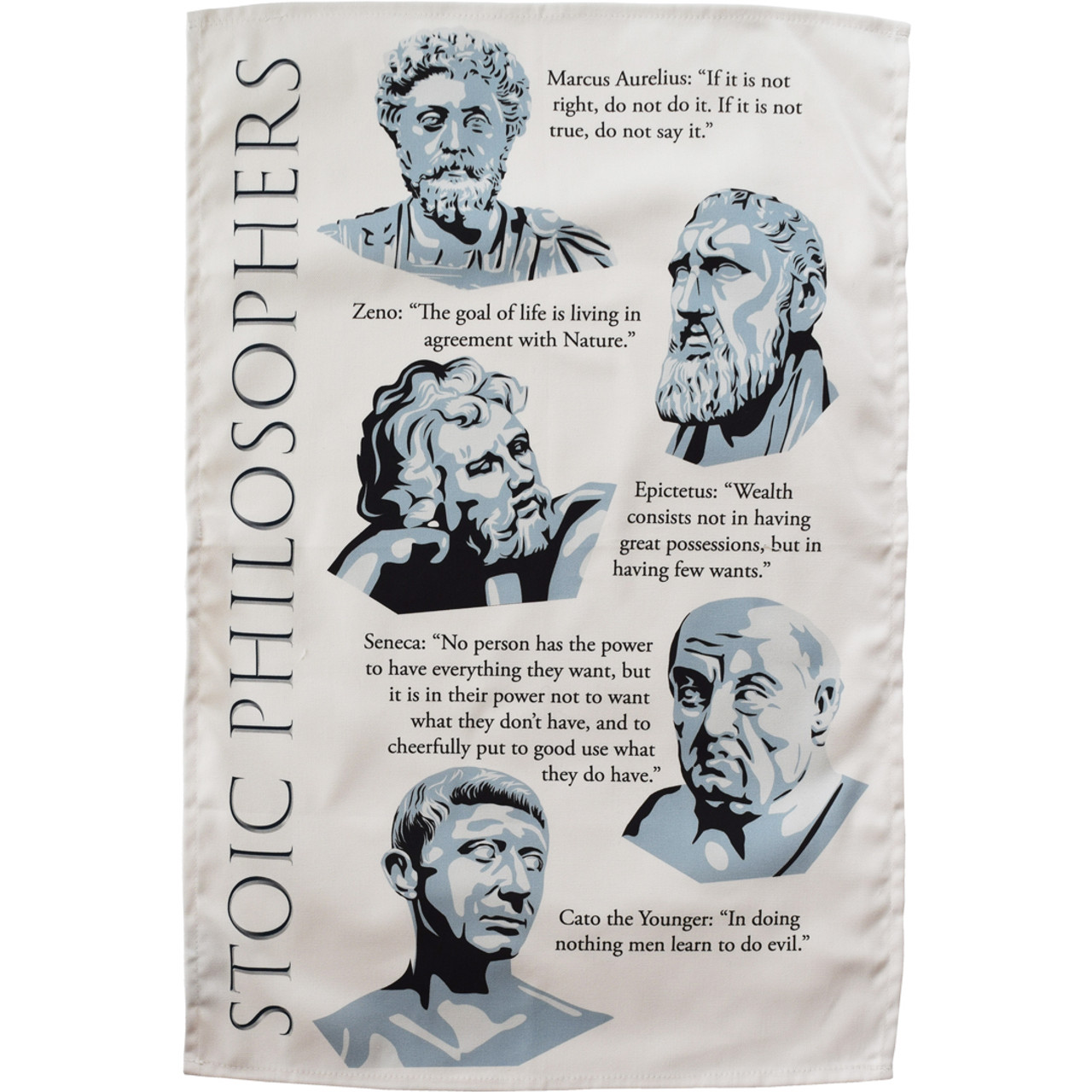

We've rarely strayed into the ancient world, but there are some interesting ideas and figures worth exploring, such as the Stoics and their challenge to materialism

See the Stoic Philosophers Tea Towel

Perhaps you know him from Kirk Douglas’ 1960 portrayal – “I am Spartacus!” – but Spartacus was a real person.

Most of the surviving evidence on Spartacus and the rebellion he led is in Roman histories written at least a century afterward.

It seems Spartacus belonged to the Maedi tribe of Thracians in what’s now Bulgaria and, based on his later successes against the Roman Army, he likely had experience soldiering before he was enslaved.

Spartacus was shipped across the Adriatic to a gladiatorial school near Capua, in southern Italy.

Once there, Spartacus and his enslaved comrades were forced to work and die as gladiators in order to entertain the idle patricians and citizens of Roman Italy.

But there was one obvious contradiction in this setup...

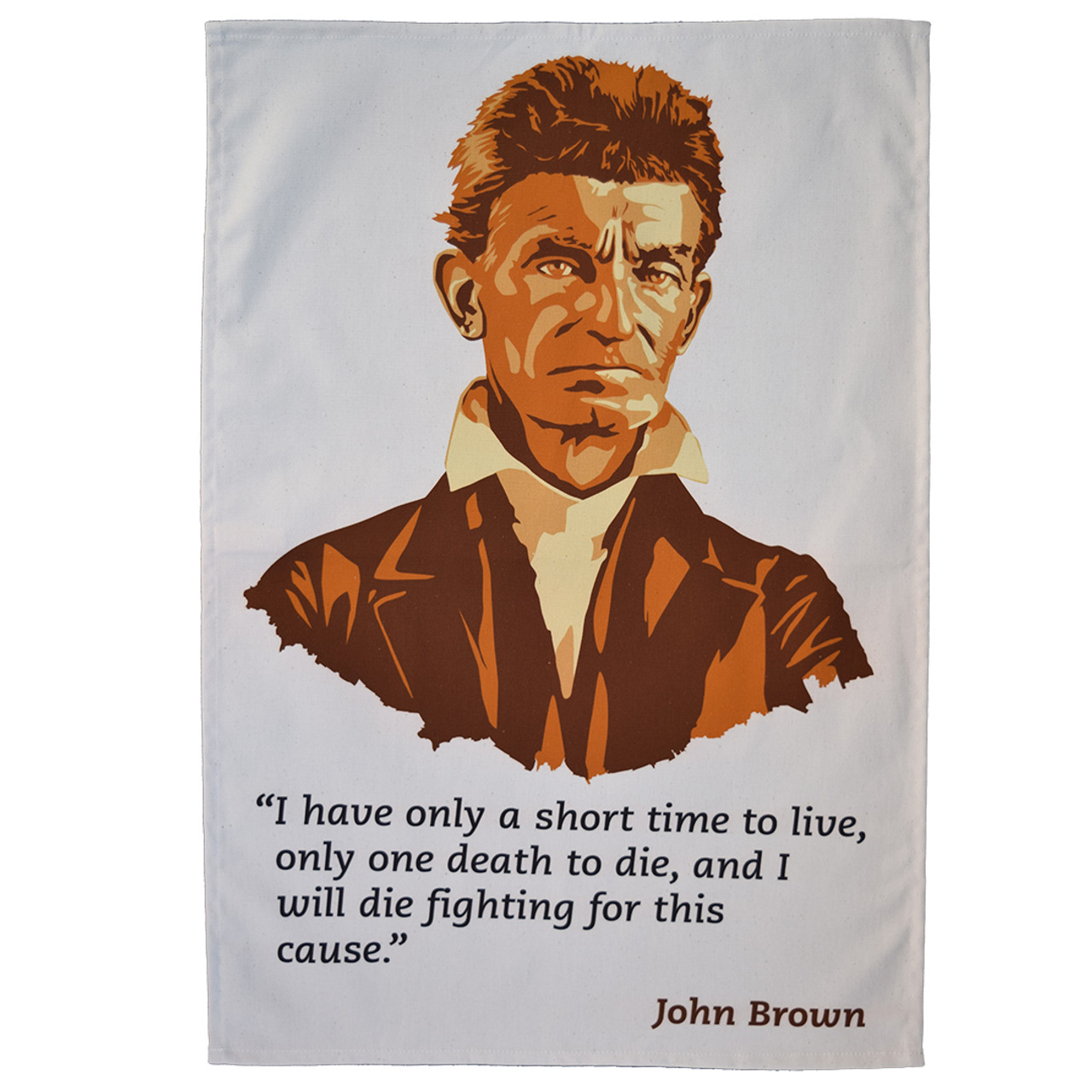

As with John Brown at Harpers Ferry in the pre-Civil War US, the institution of slavery tends to encourage violent resistance

If you impose dehumanising unfreedom and fatal conditions of labour on already-experienced warriors while giving them further military-style training and concentrating them in schools where they can organise together politically, you will face resistance.

Sure enough, in 73 BC Spartacus helped lead around 70 slaves in an uprising.

The rebel slaves seized weapons, overthrew the guards, and raided the Capuan countryside for supplies before retreating to a more defensible position on the side of Mount Vesuvius (just over a century before its infamous eruption).

So far so normal. Such everyday acts of courageous resistance would’ve been routine in a slave system.

But it was what happened next that made Spartacus’ uprising special: it lasted for two years and it grew to include 70,000 people.

With the regular army mostly abroad in Spain and Asia, fighting Rome’s wars of imperial conquest, the slave rebels in Capua had time to consolidate.

The free slaves elected Spartacus and two men from Gaul (modern France), Crixus and Oenomaus, to act as their leaders.

Using their fighting experience and Spartacus’ tactical intelligence, the rebels defeated two Roman militias sent to re-enslave them, one after the other.

Victory meant popularity, and Spartacus was able to recruit tens of thousands more people to his movement in southern Italy, both slaves seeking legal freedom and poor farmers, too.

Spartacus’ rebellion clearly had a social character, and this rattled the aristocratic elites of Rome: men who lived off the exploitation of others’ labour, free and unfree.

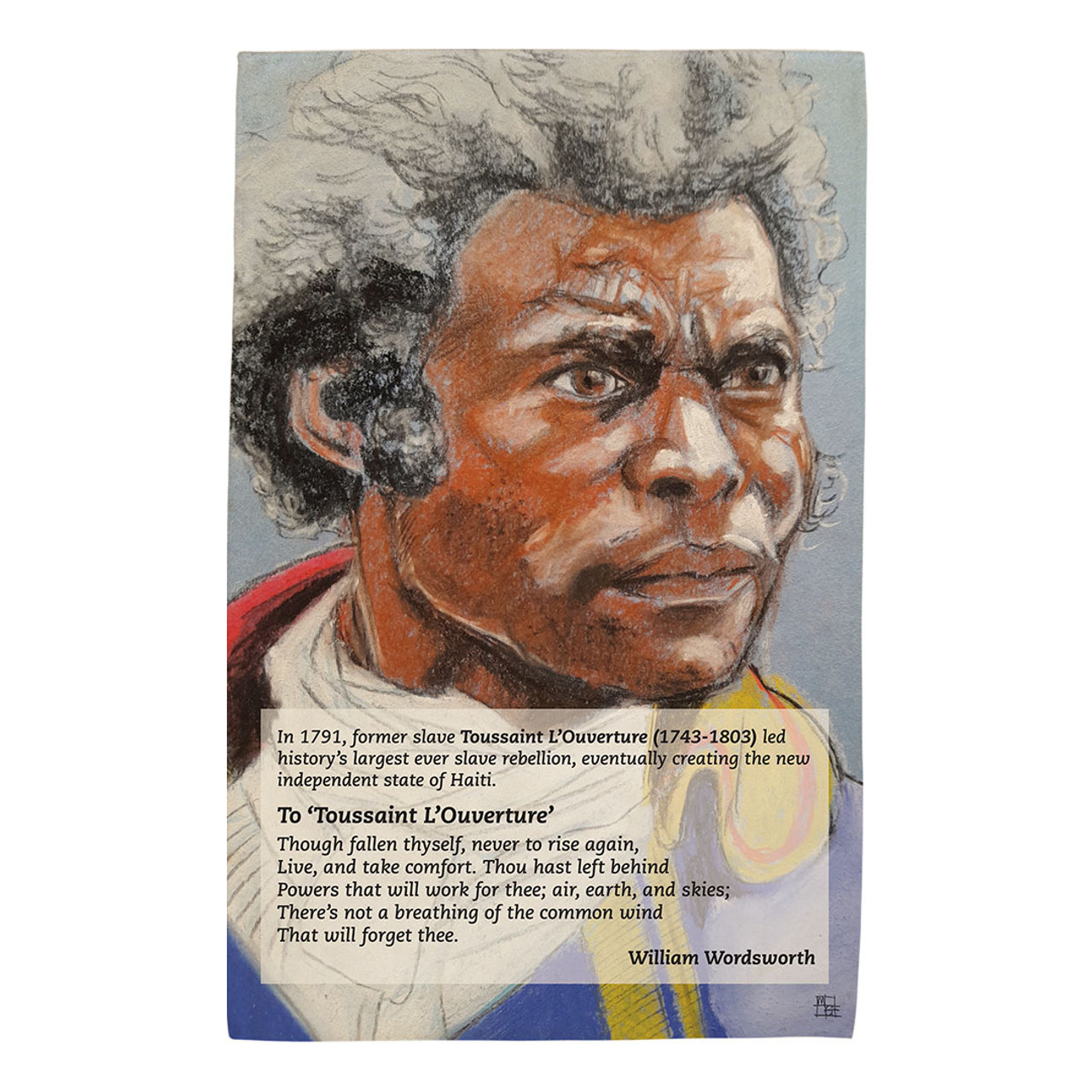

Toussaint L'Ouverture was called the 'Black Spartacus' for leading the Haitian rebellion against France

See the Toussaint L'Ouverture tea towel

While Spartacus expanded his territory in the south, the wealthy Senate nominated Marcus Licinius Crassus (known for his later run-ins with Julius Caesar), to lead no fewer than eight Roman legions – 40,000 soldiers – against the rebels.

The class conflict couldn’t have been clearer: Crassus, the wealthiest man in Rome and a vicious snob leading the repression of a freedom struggle by the most exploited people in the Roman Empire.

Against Crassus’ massive army, Spartacus’ rebels scored some early victories but they were just too outnumbered.

Cornered in the south of Italy, unable to escape, Spartacus’ army made a last stand on the road to Brundusium, where they were annihilated by Crassus’ legions.

In the counter-revolutionary terror that followed, the 6,000 rebel survivors were crucified along a 100-mile stretch of road between Rome and Capua.

It was an act of considered and spectacular ruling-class violence, meant to intimidate slaves throughout Italy.

But the radical history of Spartacus, who was probably killed in the final battle, was not done yet.

Spartacus’ image survived as a model of social rebellion and revolution, especially but not exclusively for enslaved workers across the world.

Leading the Haitian Revolution in the 1790s, Toussaint L'ouverture was praised as the ‘Black Spartacus.’

And Spartacus was the favourite historical figure of Karl Marx, who hailed him as, “the most splendid fellow in the whole of ancient history,” and:

"...a great general, noble character, real representative of the ancient proletariat."

Even the 1960 Kirk Douglas film, directed by Stanley Kubrick, has a radical history of its own.

Dalton Trumbo was the screenwriter of Spartacus despite the fact he’d been blacklisted in 1947 as one of the heroic ‘Hollywood Ten,’ writers and directors who refused to comply with the reactionary House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) – a modern-day Crassus.

Kirk Douglas defiantly announced that Trumbo was working on Spartacus in 1960, a fact which, along with the story’s class-struggle politics, provoked the American Right to denounce the film and call for it to be banned.

But they failed, and their failure to censor Spartacus was a major blow to McCarthyism in Hollywood.

The radical history of Spartacus, then, which began over 2,000 years ago, is to be continued...