The American Revolution: The Shot Heard Around the World

Posted by Pete on 18th Apr 2025

Since 1775 the Battles of Lexington and Concord have been part of debates about what freedom means in America and what America means to the world...

“Here once the embattled farmers stood,

And fired the shot heard round the world.”

It is 250 years since the first fight of the American Revolution.

On 19 April 1775, a few thousand American militia held off the British Army at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in rural Massachusetts.

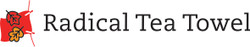

Even after the American Revolution, the new United States remained a place of rebellion - which many saw as a healthy thing

See the Shays' Rebellion tea towel

British regulars had been sent out from Boston to seize local weapons.

The ‘redcoats’ drove the American militia out of the small town of Lexington before being stopped by the Americans at the Old North Bridge in Concord, then routed.

The militia chased the British all the way back to Boston and put the town under siege.

That siege force was soon turned into the ‘Continental Army’ proper, the revolutionary fighting force of the American rebels.

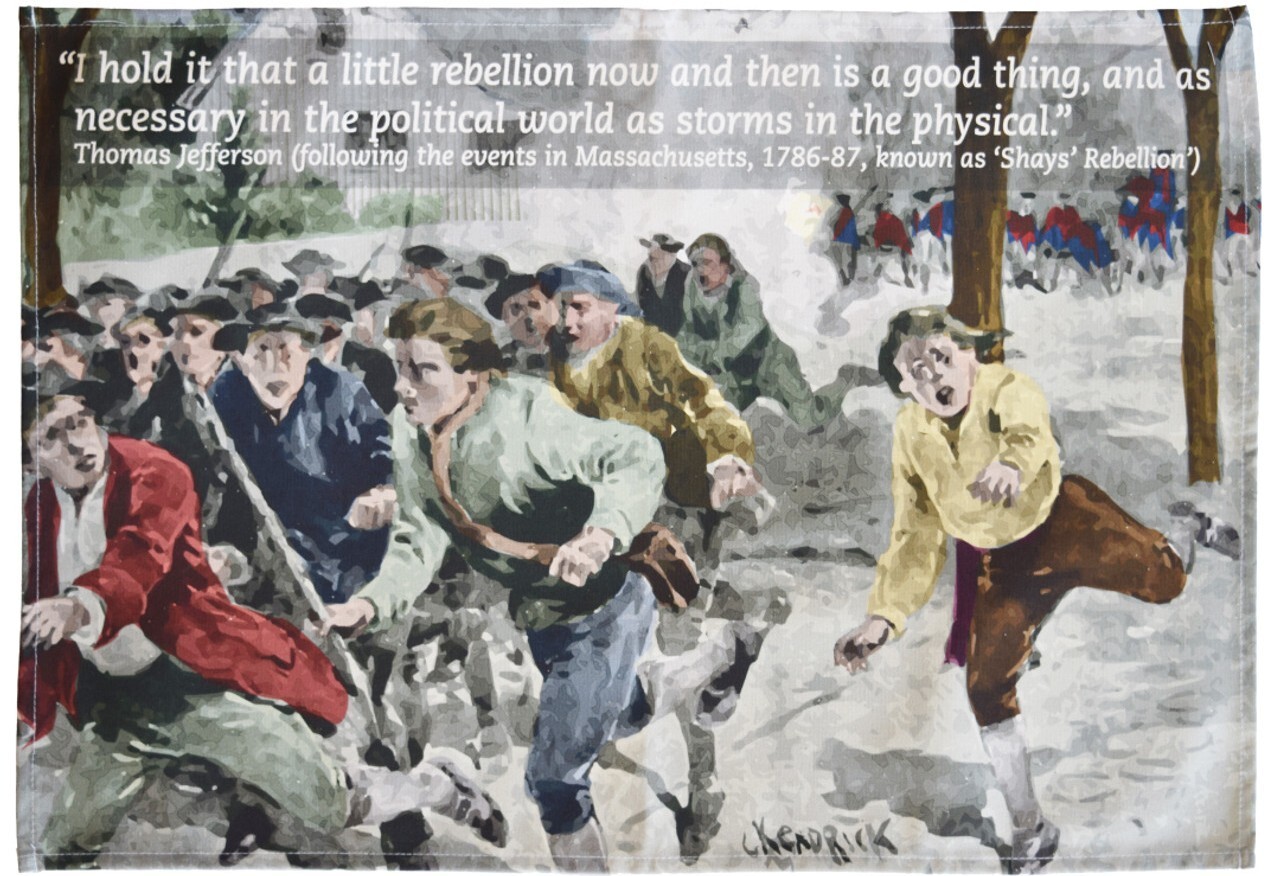

A year after Lexington and Concord, in 1776, the Continental Congress declared independence outright.

Soon enough, the new American Republic was a recognised fact. The British Empire was beat.

But the story of Lexington and Concord didn’t end there.

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were a precursor to the Declaration of Independence exactly a year later

See the Declaration of Independence tea towel

After the Revolutionary War, the twin battles were turned into a foundation myth of the United States, and a bedrock of American identity.

The poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, who inspired later U.S. idealists like Walt Whitman and John Muir, was there at the unveiling of the Concord Monument in 1836.

His ‘Concord Hymn’ coined the line “the shot heard round the world” to describe the outbreak of the American Revolution.

Emerson was an abolitionist, too, and over the mid-nineteenth century, the meaning of the American Revolution became part of the internal struggle over slavery in the U.S.

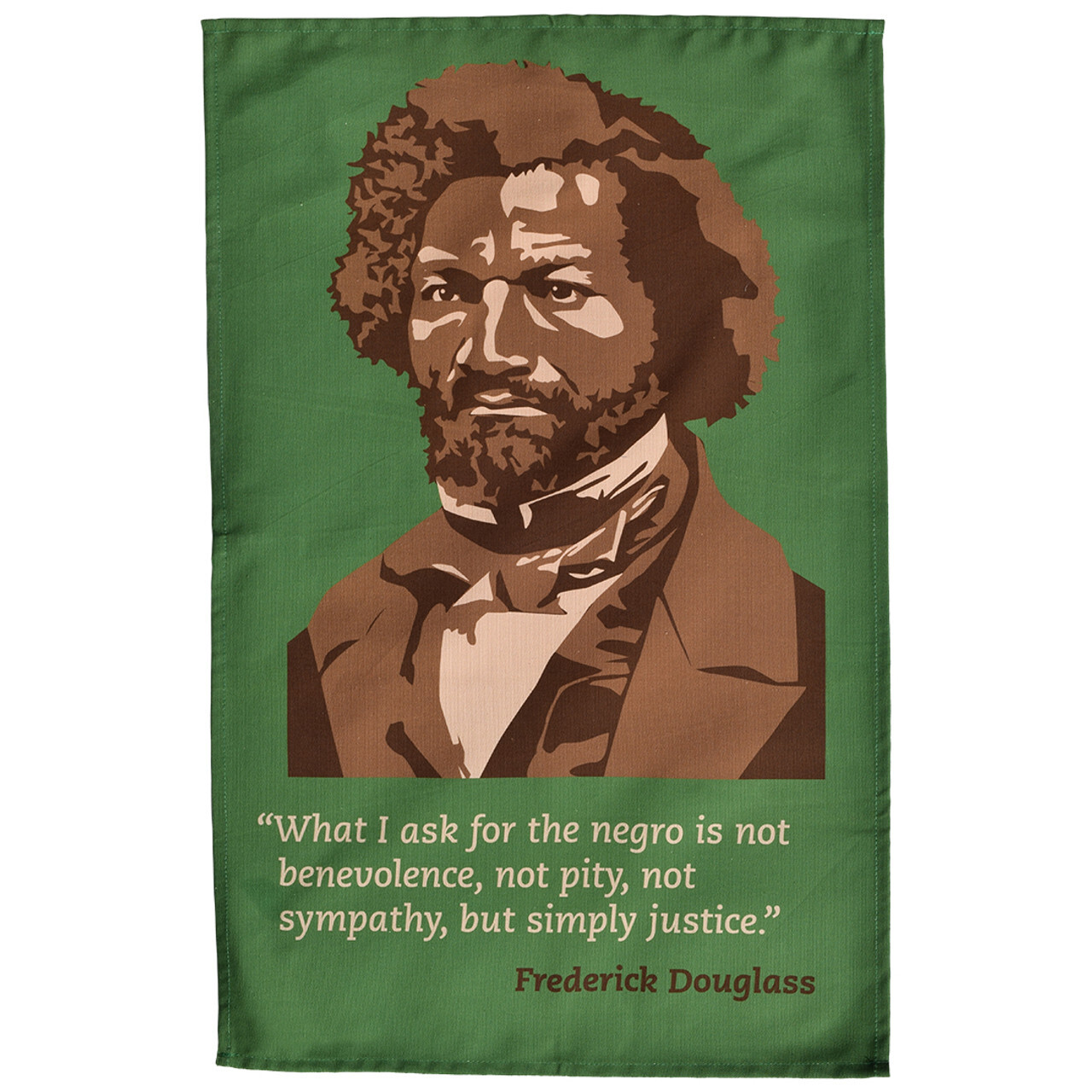

Anti-slavery activists like Frederick Douglass asked ‘what to the slave is the Fourth of July?’

If the American Revolution had been for freedom, why was the United States still based on the enslavement of millions of black people?

Frederick Douglass lamented the hypocrisy of the US's failure to make the Revolution's ideal of liberty something in which all Americans could share

See the Frederick Douglass tea towel

And once the Civil War began in 1861, the Union war effort was seen as a struggle to redeem the ‘unfinished’ American Revolution by ending slavery.

Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address famously began with a reference back to the Revolutionary War:

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

After the Civil War, Ulysees S. Grant, Lincoln’s favourite general, was President at the time of the centenary of Lexington and Concord.

Grant and his cabinet joined the celebrations in 1875, including the new Minute Man sculpture by Daniel Chester French.

The statue had been recast from the bronze of Civil War cannons, and it represented a Massachusetts militiaman – called ‘minutemen’ because they could be ready to fight with just one minute’s notice.

The Minute Man statue at Concord, with Emerson’s lyrics on the pedestal, quickly became another symbol of American freedom, and of the ongoing struggle over its meaning and reach.

Women’s suffrage campaigners regularly gathered at the statue to demand the vote, after their exclusion from the original unveiling.

And the history of Lexington and Concord was really “heard round the world,” too.

The statue marking the centenary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord was used by women's suffrage campaigners as a protest spot, following their exclusion from its unveiling

See the Woman Registered to Vote tea towel

Anticolonial movements globally have used the American example of 1775 to justify their struggles, even once the United States had become an ally of European empires in the twentieth century.

Ever since 1775 the Battles of Lexington and Concord have been part of debates about what freedom means in America and what America means to the world.

Those remain open and volatile questions, and for so long as they do, the minutemen and the redcoats, Lexington Common and the Old North Bridge at Concord, will continue to matter in the present as much as they did 250 years ago.