The Common Name of Irishmen: Wolfe Tone and the Irish Rebellion of 1798

Posted by Pete on 19th Nov 2021

The story of Wolfe Tone and the origins of Irish Republicanism...

Theobald Wolfe Tone, the founder of Irish republicanism, died today in 1798 while awaiting execution by the British state.

A Dubliner, born in 1763, Tone was involved in the struggle for political equality in Ireland from a young age.

Back then, it was the British-ruled ‘Kingdom of Ireland.’ As in the rest of the British Isles, non-Anglicans were disenfranchised and excluded from significant public offices.

This system was fundamentally anti-Irish. Most people in Ireland were Catholic and many of the rest were non-Anglican Dissenters. The country was ruled by a tiny minority of elite Protestants.

But Wolfe Tone, despite being Anglican himself, was a vocal supporter of Catholic emancipation.

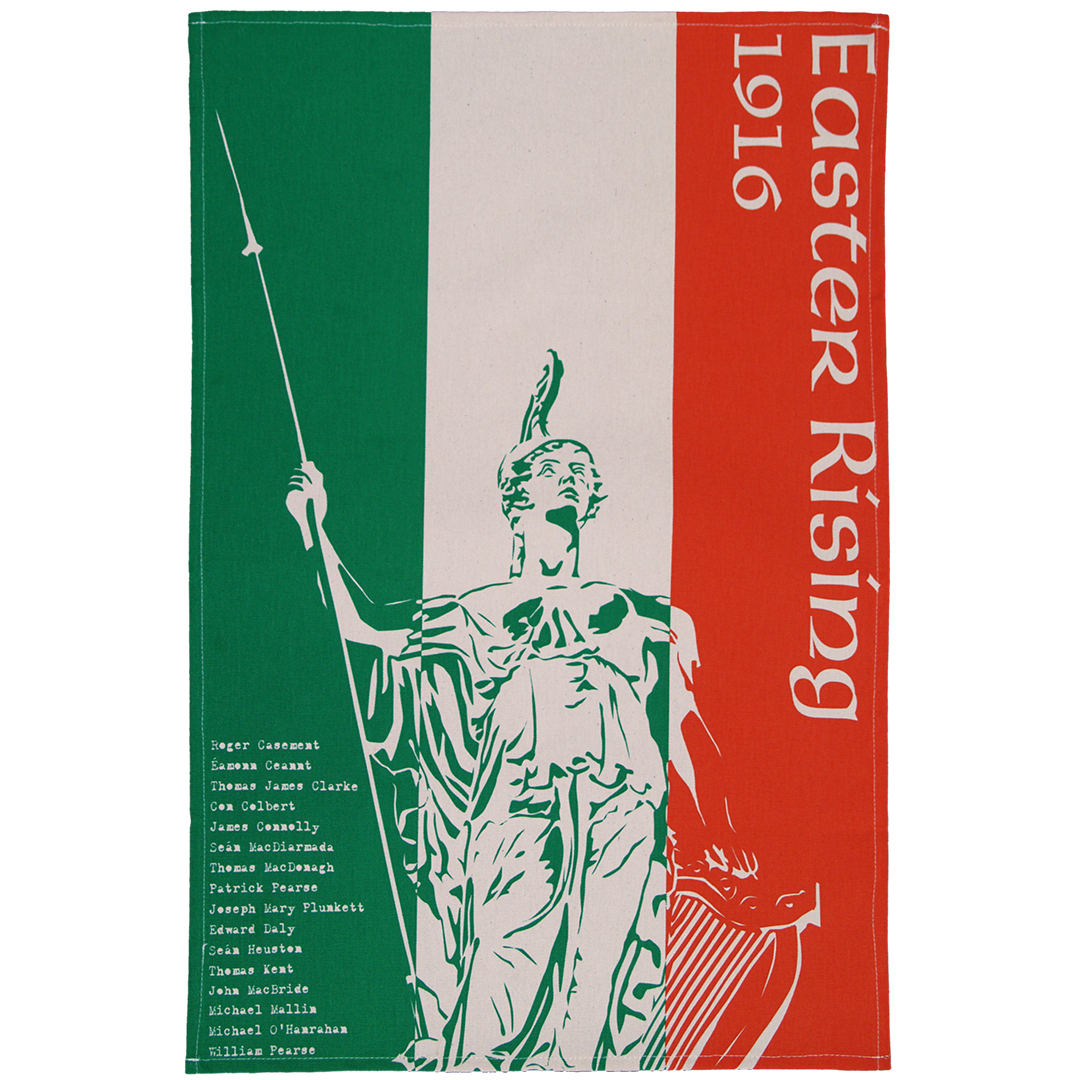

The Easter Rising of 1916 was part of an Irish revolutionary tradition which goes back to Wolfe Tone and the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

Click to view our Easter Rising tea towel

After making a name for himself with the pamphlet,

An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland, he co-founded the Society of the United Irishmen at a meeting in Belfast in October 1791.

Wolfe was quite clear about what he wanted to achieve:

"To subvert the tyranny of our execrable government, to break the connection with England… and to assert the independence of my country – these were my objects. To unite the whole people of Ireland, to abolish the memory of all past dissensions, and to substitute the common name of Irishmen in place of the denomination Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter – these were my means."

Initially quite moderate, the United Irishmen called for cooperation across religious divides in Ireland to better prevent England exploiting the country as a whole.

But this was also the decade of the French Revolution, which did not pass Ireland by…

An 18th Century Portrait of Wolfe Tone

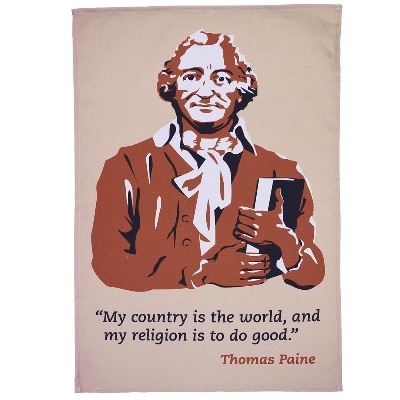

Wolfe Tone became an early admirer of the French cause, especially republican leaders like Georges Danton and the globe-trotting Englishman,

Tom Paine.

International politics also attracted Irish radicals to the French Republic, which had been at war with Britain since 1793.

People like Wolfe began to dream of an expedition by the powerful French army, which could liberate Ireland from British rule altogether.

He pictured an Irish Republic without hierarchy among the religions. Tone even had a streak of economic radicalism:

"If the men of property will not support us, they must fall. Our strength shall come from that great and respectable class, the men of no property."

The key allies of British rule in Ireland were the landowners, after all – as usual, the ‘men of property’ were happy enough with the status quo.

But all this dreaming of revolution by the United Irishmen scared the British government.

Wolfe Tone was a disciple of Thomas Paine and deeply inspired by the revolutions in America and France.

Click to view our Thomas Paine tea towel

Terrified of revolution, the state was

cracking down on civil liberties during the 1790s. And, as with most periods of repression in British history, it was most violent in Ireland.

Severe repression of the United Irishmen drove Wolfe Tone into exile in the US.

Tone moved quickly on to Paris, where he lobbied for a French invasion of Ireland: "good for your war against Britain, good for our freedom."

And the French Republic did mobilise a major army – over 14,000 soldiers – which, had they reached Ireland, would likely have cleared out the British forces there.

But they did not reach Ireland. Having sailed in December 1796, with Wolfe Tone aboard as an officer attached to the commanding general, Lazare Hoche, fierce storms blew them back to France.

This was the first of many decisive setbacks for Wolfe.

Then, in May 1798, the United Irishmen began their rebellion, regardless of French support.

The problem was that Wolfe Tone was still in Paris.

He begged the French government to intervene, but they decided to spare only a few raiding squadrons, with Tone among them.

Sadly, these ships arrived too late, allowing the British enough time to overwhelm the poorly-armed Irish rebels.

Wolfe was captured when his fleet was defeated by the Royal Navy off Donegal in October 1798.

Quickly sentenced to hang for treason against a country he viewed as a foreign enemy, Wolfe Tone was either shot by one of his British captors or took his own life before his execution.

But his dream of an independent Irish Republic proved unkillable.

In 1949, on the anniversary of the

Easter Rising and just over 150 years after Wolfe Tone’s death, the Republic of Ireland was made real.

The arc of history is long but it bends, oh so slowly, towards justice.

Key dates in Wolfe Tone's Life:

- 20 June 1763: Theobald Wolfe Tone born in Dublin.

- February 1786: Graduates from Trinity College Dublin.

- May 1789: The French Revolution begins.

- September 1791: Tone publishes An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland.

- October 1791: Co-founds the Society of the United Irishmen.

- April 1792: Catholic Relief Act passed by Parliament, marginally reducing legal restrictions on Catholics and briefly weakening radical support.

- 1794: The United Irishmen become committed to an independence revolution against British rule.

- May 1795: Wolfe Tone arrives in the US for a period of political exile.

- February 1796: Arrives in Paris to lobby for French intervention in Ireland.

- 15 December 1796: The ill-fated Hoche Expedition to Ireland sets sail, soon to be blown back to France by bad weather.

- May 1798: The United Irishmen rise up against British rule.

- 12 October 1798: Wolfe Tone captured by the British after the naval defeat of the French at the Battle of Tory Island off Donegal.

- 12 November 1798: Sentenced to death for treason by a British court-martial in Dublin.

- 19 November 1798: Wolfe Tone dies or is killed in British captivity prior to execution.