The Dalai Lama: A Political Figure, and a Socialist

Posted by Pete on 27th Mar 2025

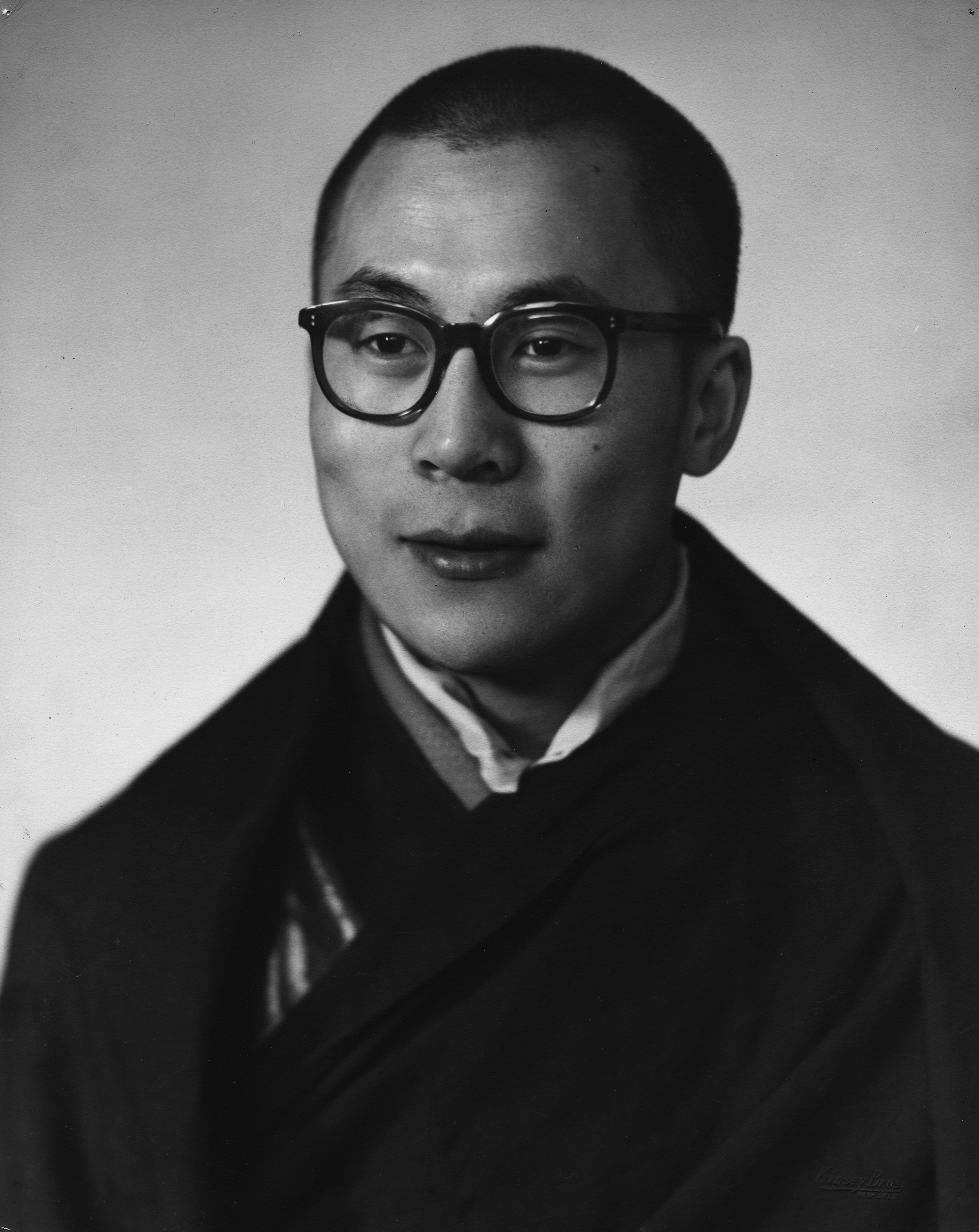

The 14th Dalai Lama was a political figure who came to represent his nation from afar

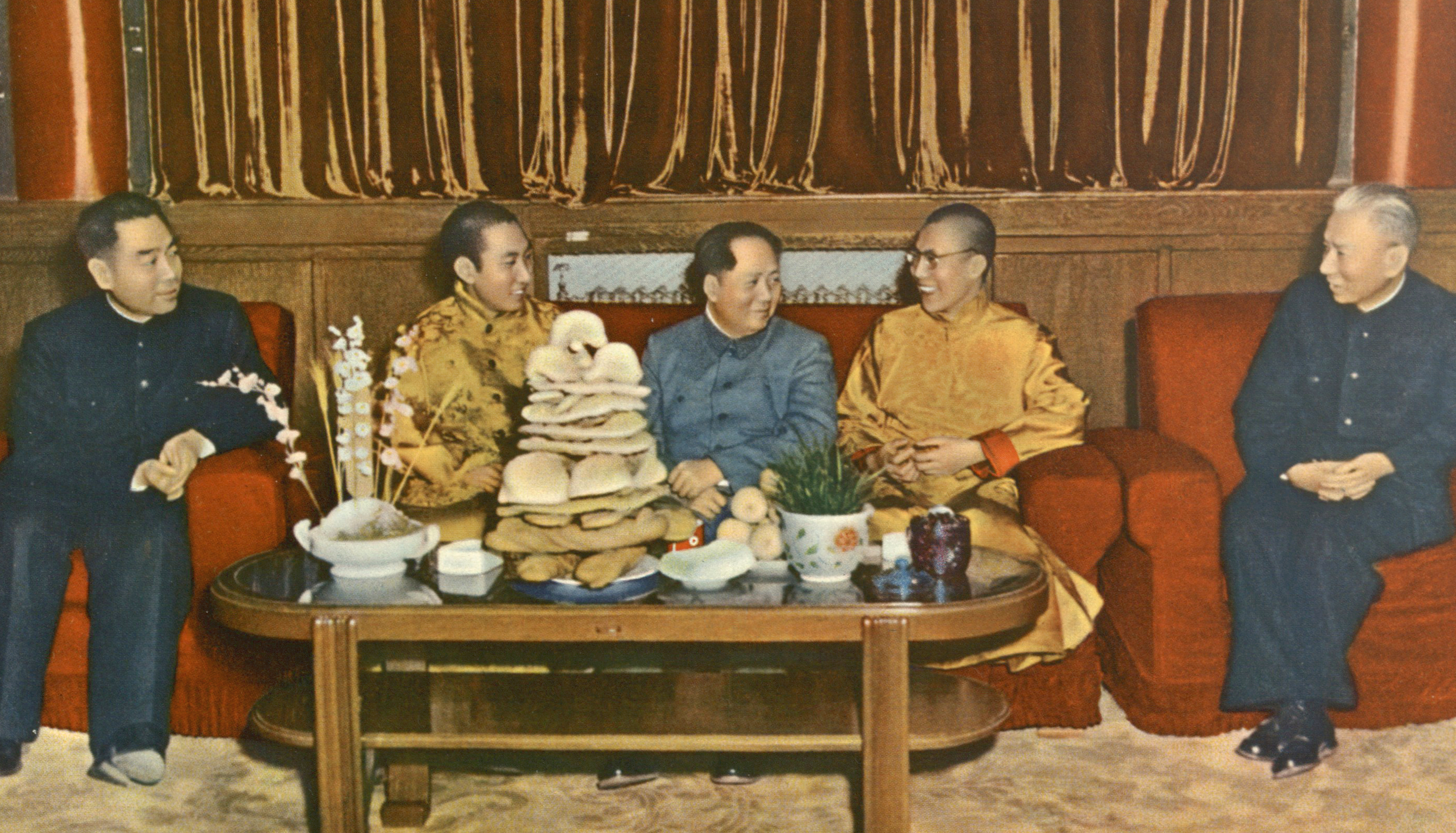

The Dalai Lama met Mao Zedong in 1955 to celebrate Tibetan New Year. He had initially sought to cooperate with the communist regime.

You’d be forgiven for imagining that the Dalai Lama, the head of Tibetan Buddhism, was a religious figure.

But he’s a political actor, too.

And briefly, during the 1950s, he actually governed Tibet until, on 30 March 1959, the Dalai Lama had to flee the Chinese army into a life of foreign exile.

The Dalai Lama didn't go quietly as he fled Tibet - he's been speaking up, kindly, ever since

See the New Dalai Lama tea towel

The spiritual office of Dalai Lama ruled Tibet – the Himalayan “roof of the world” – as a Buddhist political community since the mid-1600s.

For most of that time, Tibet remained loosely dependent on the Chinese empire.

But in 1913, the 13th Dalai Lama took advantage of the republican revolution launched in China by Sun Yat-sen to declare Tibetan independence outright.

China didn’t forget about Tibet.

Already by the late 1930s, the Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai-shek was putting pressure on Tibet through its allies in the nearby Chinese province of Qinghai.

One of these warlords even arrested the child Lhamo Thondup (b. 1935) – soon to become the 14th and still current Dalai Lama – en route to his formal election in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa.

Bribing his way out of captivity, the new Dalai Lama was formally enthroned in February 1940 – when he was still just four years old.

That’s because the selection process for a new Dalai Lama involved senior monks searching Tibet for a child deemed to be the reincarnation of the previous one, who had died in 1935.

Tibet wasn't the only region to clash with the authoritarian Chinese government - though Hong Kong had until recently seemed to enjoy more autonomy

Hong Kong Umbrella Movement tea towel

The former Lhamo Thondup spent his early years as Dalai Lama studying Buddhism.

Meanwhile, Chiang Kai-shek continued to coerce the Tibetan government, including attacks on Buddhist monasteries in the borderlands.

But during the 1940s, China was distracted by the war against Imperial Japan’s brutal invasion and occupation of its eastern territories, and afterwards by the Chinese Civil War.

In 1949, Mao Tse-tung’s Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its Red Army won the civil war on the mainland, founding the People’s Republic of China.

This put Tibet in a tough spot.

China was now mostly united for the first time since the Revolution of 1911, and its new Communist government was hostile to Tibetan independence.

Mao saw Tibet as a splinter state whose existence violated the historic unity of China.

He also saw Tibet’s Buddhist government as a form of theocratic feudalism, anathema to communist principles.

What’s more, in October 1950 the first contingents of the Red Army arrived at the edge of Tibetan territory.

The 14th Dalai Lama in 1956

Amid this takeover scare, the Dalai Lama – aged 15 – was hastily made to assume full political authority in Tibet, five years earlier than normal.

In 1951, a Tibetan delegation was sent to Beijing, 7,500 miles away.

Without authorisation from Lhasa, the envoys agreed to recognise Chinese sovereignty over Tibet in return for internal autonomy.

The Dalai Lama, trying to make the best of a bad situation, sought to build better relations with Mao.

Still just 19, he toured China in 1954-5, meeting Mao and the rest of the government in Beijing.

The Dalai Lama was actually quite keen on the egalitarian principles of socialist thought, despite his Buddhism, but he was still committed to Tibetan self-government.

And this became a bigger problem as the 1950s progressed.

Mao’s government, increasingly secure in Beijing, began to put more pressure on Tibet.

Chinese philosopher Confucius's ideas about morality and relationships began to catch on around the time of the Ancient Greek philosophers

Things came to a head on 10 March 1959 when, prompted by rumours that the Chinese government planned to arrest the Dalai Lama, the people of Tibet launched a massive uprising that soon demanded independence from China.

But the Tibetan rebels were no match for the Red Army, and the uprising had made the Dalai Lama’s presence in Tibet untenable.

So, on 30 March, the Dalai Lama fled to India, where Jawaharlal Nehru’s government agreed to give him political asylum.

A kind of Tibet-in-exile was then set up by thousands of refugees in Dharamshala in the Indian province of Himachal Pradesh, from where Tibetans have continued to agitate for self-government and other progressive causes, such as the U.N Declaration of Human Rights and nuclear disarmament, ever since.