The Meaning of Homeland: World Refugee Day

Posted by Pete on 20th Jun 2024

Photo by Ra Dragon on Unsplash

Today we're celebrating World Refugee Day and the refugees who wrote the story of radical history across the world

You ask: What is the meaning of “homeland”?

They will say: The house, the mulberry tree, the chicken coop, the beehive, the smell of bread, and the first sky.

You ask: Can a word of eight letters be big enough for all of these, yet too small for us?

The Palestinian writer, Mahmoud Darwish, wrote these lines in his poem, ‘In the Presence of Absence.’

Darwish was a refugee.

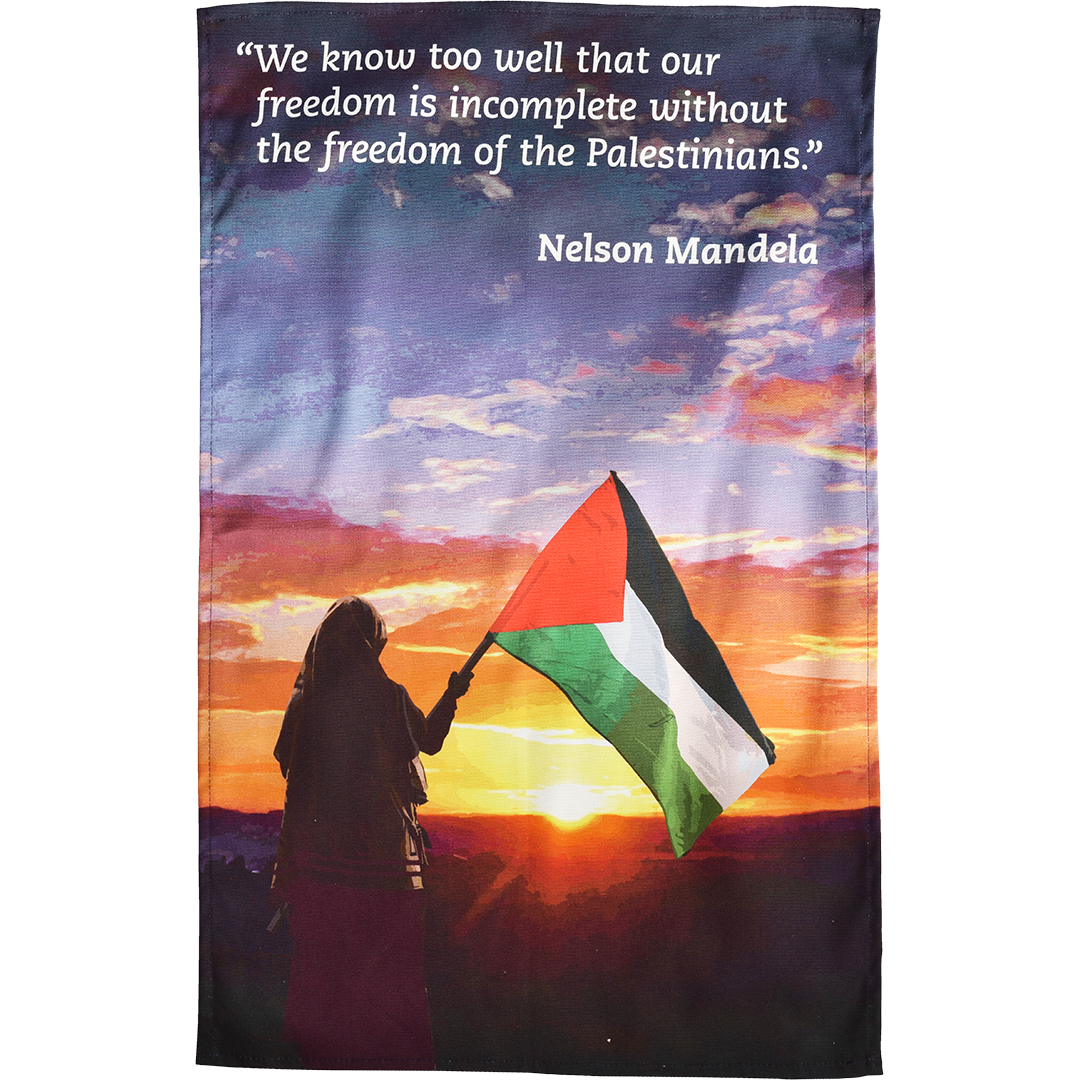

During the 1948 Nakba, when Arab Palestine was ethnically cleansed to make way for the creation of the state of Israel, Darwish’s family were driven from their home in the Palestinian village of al-Birwa by the Haganah, a Zionist militia and precursor to the Israeli army.

For every tea towel sold we donate £1 to Medical Aid for Palestinians

Darwish and his family, like millions of their Palestinian compatriots, were never allowed to return to their stolen homes.

He died in Houston, Texas, in 2008.

Today is World Refugee Day, created by the United Nations in 2001 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, and to renew the global commitment to the rights of those seeking refuge abroad.

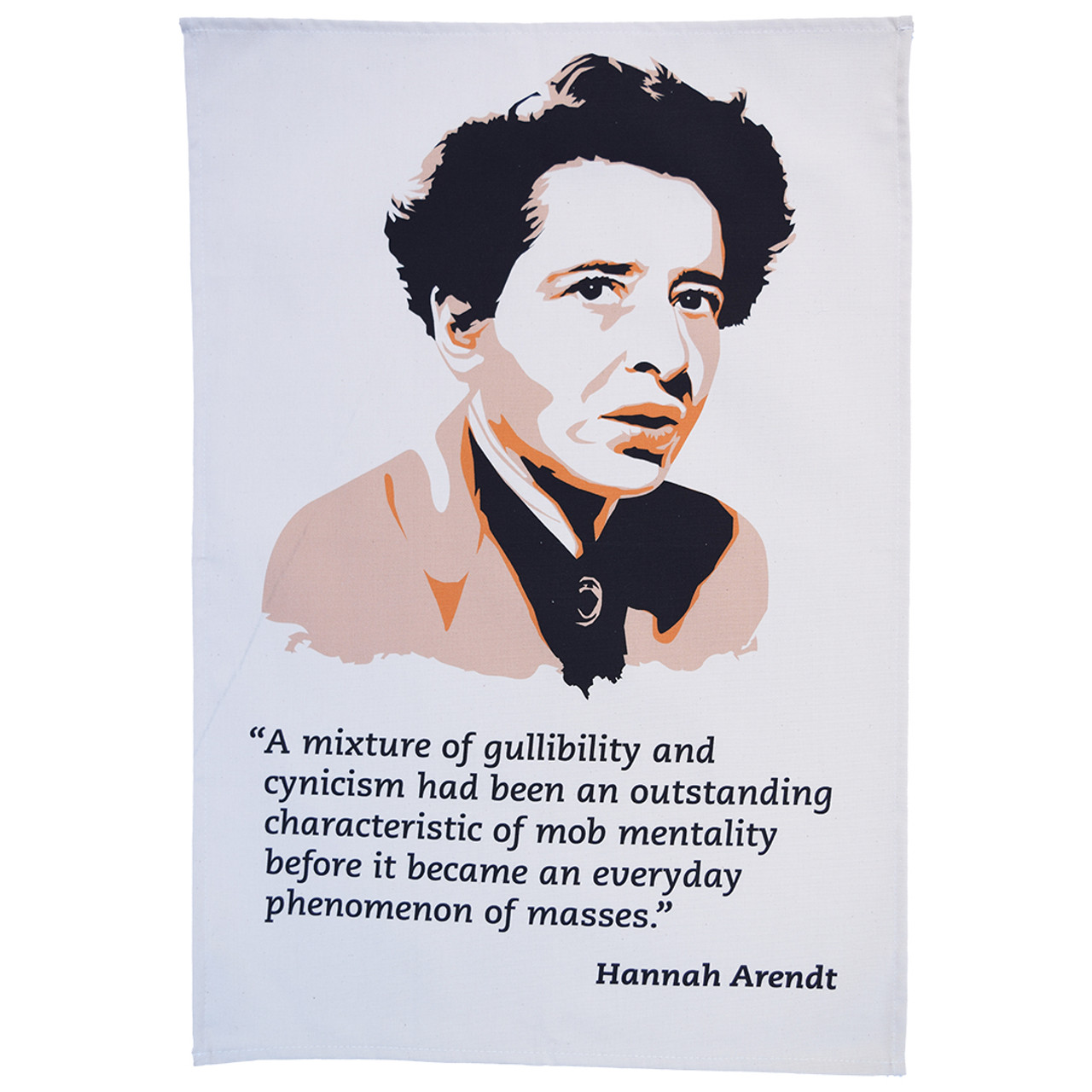

As Hannah Arendt – herself a Jewish refugee from Nazism – argued, refugees often live without the “right to have rights.”

Arendt’s point is that crucial human rights – to physical security, political self-government, various social goods – need a state to enforce them for its citizens. But refugees don’t have a state of their own.

One of the most influential political theorists of the twentieth century, Arendt fled Germany in the 1930s and made it to the United States in 1941

See the Hannah Arendt tea towel

The insecurity of stateless people is why one of the main threads of refugee politics in radical history has always been the demonstration of human solidarity and compassion by groups of citizens towards people seeking refuge in their community.

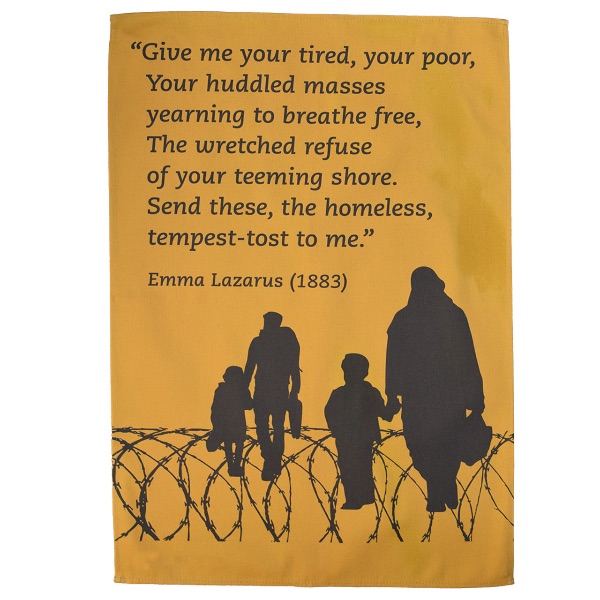

Hence the iconic inscription by Emma Lazarus on the Statue of Liberty in New York, intended to welcome refugees to the city:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

But Lazarus was an activist as well as a poet.

During the 1880s, she was involved in campaigns to provide aid to Jewish refugees arriving in New York to escape the anti-Semitic pogroms in the Russian Empire.

For every tea towel sold we donate £1 to the charity Refugee Action

See the Refugee Emma Lazarus tea towel

So much of radical history, in fact, has been written by refugees.

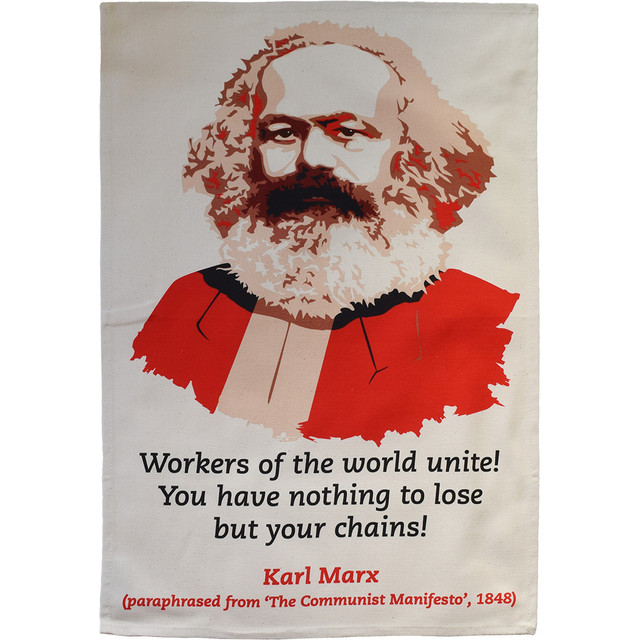

Nineteenth-century Europe was full of political refugees, including Giuseppe Mazzini, Lajos Kossuth and Karl Marx, who had been driven from their home countries by authoritarian regimes.

Rather than abandon their political activism in favour of personal security – an extremely legitimate choice in the circumstances – these radical exiles only intensified their efforts to achieve social and national liberation for Europe and the wider world.

Oftentimes, the experience of being a refugee actually heightened the radicalism of these activists, especially in terms of internationalism.

Seeing first-hand how reactionary states could chase down dissidents across borders, thinkers like Marx gained a deeper appreciation of why the popular classes needed to resist on an international scale, too.

Perhaps the most iconic radical of all, Karl Marx spent much of the 1840s fleeing oppressive governments in Europe

Meanwhile, republican exiles from the Spanish Civil War grouped together and continued their anti-fascist project as volunteers in the Allied armies during WW2.

And Palestinian refugees, including Mahmoud Darwish, have continually demanded their right of return to their homes, from the moment of the 1948 Nakba onward.

One of the main symbols of Palestinian resistance and solidarity is the key, symbolic of their right to return to the homes that were stolen from them.

The global history of refugees is full of progressive stories of hospitality, solidarity, and liberation.

At a time when forced displacement of human beings is, if anything, becoming more intense, these stories of solidarity and hope can give us light in the dark.