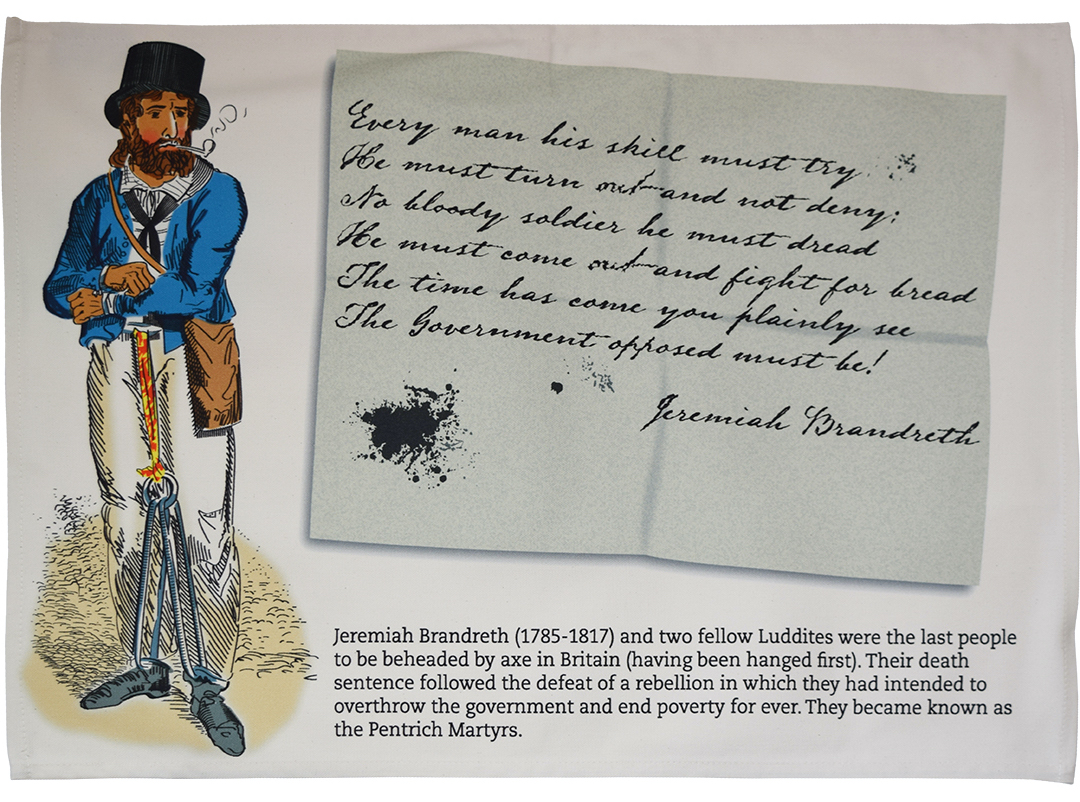

The Nottingham Captain: Jeremiah Brandreth and the Pentrich Revolution

Posted by Pete on 7th Nov 2023

Brandreth and his fellow Pentrich Martyrs were executed for treason on this day in 1817

Britain didn’t have a revolution like France. But we nearly did.

In 1817, during the recession after the Napoleonic Wars, unemployed artisans in the Derbyshire village of Pentrich rose up to overthrow the British government.

And

the Pentrich revolutionaries were no disorganised mob. They had a clear sense of political purpose: to dissolve the national debt, overthrow the government, and “end poverty forever”.

They also had leadership: in particular, they had Jeremiah Brandreth, from Wilford in Nottinghamshire.

As the revolutionaries marched, Brandreth led the singing: 'The time is come you plainly see / The government opposed must be.'

See the Jeremiah Brandreth tea towel

In 1817, Brandreth – ‘The Nottingham Captain’ – was an unemployed stocking maker living in Sutton-in-Ashfield with his wife and three children.

He’d been involved in Luddite activism during the early 1810s. But in 1817, he committed himself to a broader form of working-class struggle.

In the spring of 1817, as unemployment and poverty soared across the British isles, Brandreth planned to lead a column of Nottinghamshire workers to overthrow the government in London.

It was a radical response to workers’ misery in the early nineteenth century, but Brandreth was in many ways representative of his class.

It was normal to be radical if you were an artisan in post-Napoleonic Britain.

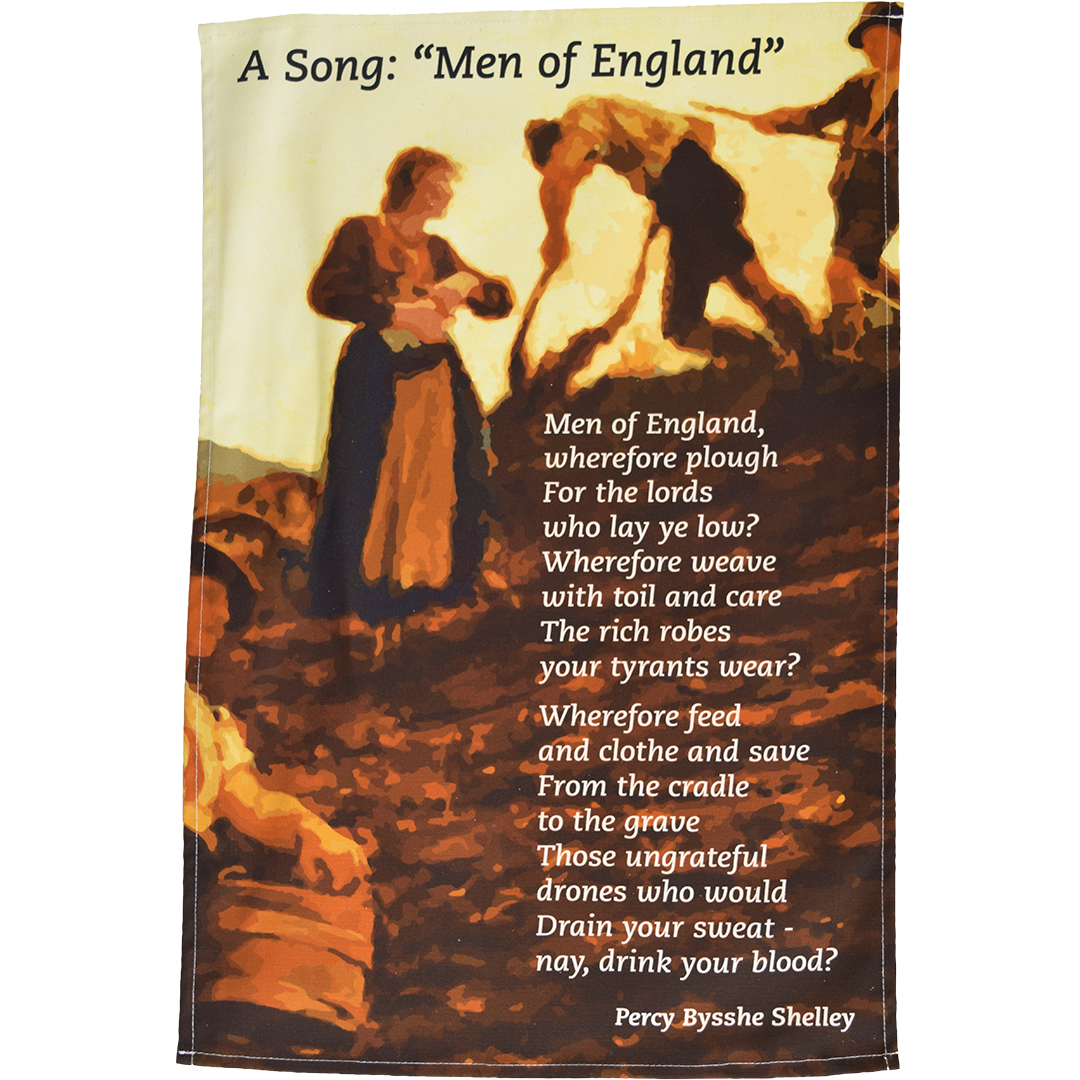

The merciless advance of capitalist industrialisation had been destroying the material autonomy and dignity of skilled artisans since the eighteenth century.

Production was mechanised, making artisanal expertise redundant. The income of skilled workers plummeted, or else they lost employment altogether.

Radicalism stirred across Britain in the early 1800s, captured here in Shelley's poem 'Men of England'

See the Shelley Men of England tea towel

Meanwhile, MPs in London who were mostly landed aristocrats and business tycoons, didn’t care.

To them, the impoverishment and death of labourers in Britain and Ireland was the necessary and worthwhile cost of economic “progress.”

To make matters worse, humble artisans like Jeremiah Brandreth didn’t have any parliamentary means to voice their dissent: until the 1860s the vast majority of the British working class was disenfranchised by property requirements for voting.

‘Representative government’ in nineteenth-century Britain was a sham. The country was run by a dictatorship of property-owners.

With constitutional politics closed off to the working class, it was unsurprising that people like Brandreth chose insurrection.

On 9 June 1817, Brandreth led a column of between 200 and 300 men from Pentrich towards Nottingham.

The rebels included stockingers like Brandreth, who worked in textiles, but also local quarrymen and iron workers, all victims of rampant industrialisation, postwar depression, and the neglect of an oligarchic government.

The Pentrich revolutionaries were lightly armed, and had some skirmishes with local law officers and employers.

But the revolution was sadly undone from the inside: Brandreth’s organisation had been infiltrated by a Home Office spy, William Oliver, who had reported the whole plan to the government.

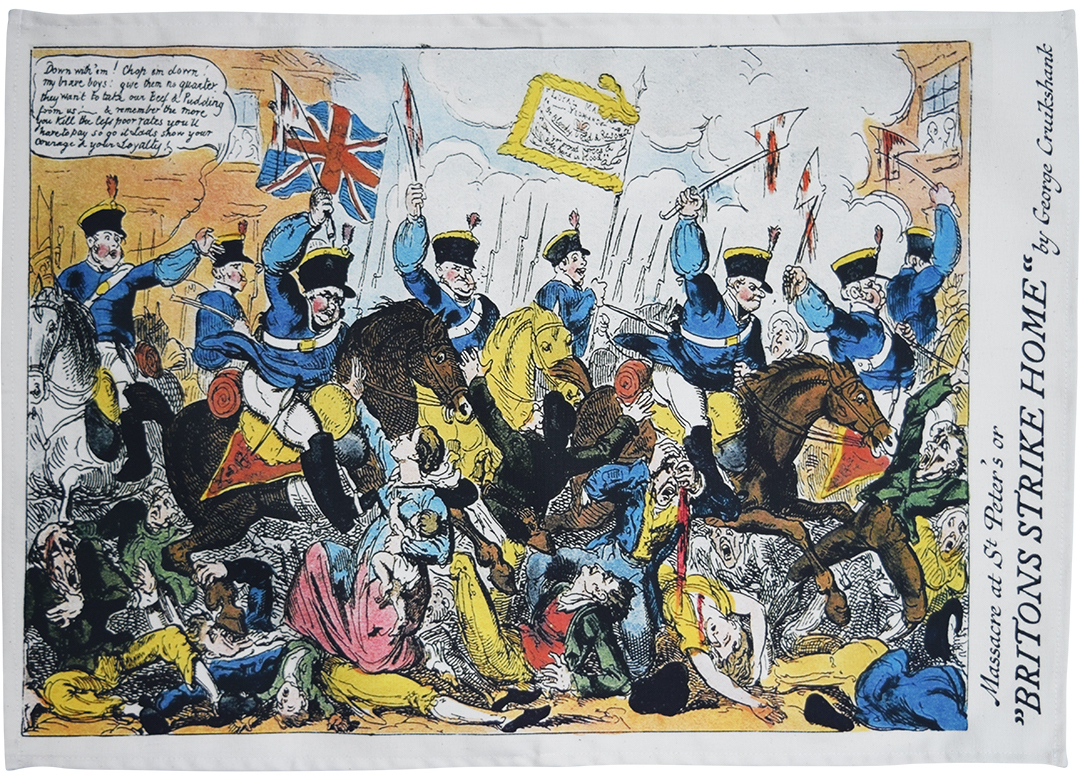

The Peterloo Massacre took place just two years after the Pentrich Revolution

See the Peterloo Massacre tea towel

The revolutionaries were ambushed by the army at Giltbrook, and routed.

After a few months on the run, Brandreth was captured and sentenced to death for high treason at the Old Bailey.

With his fellow revolutionary leaders, William Turner and Isaac Ludlam, Jeremiah Brandreth was the last person to be beheaded by the British state.

The use of such a medieval punishment was a sign of how much the ruling class in Georgian Britain wanted to secure the political obedience of workers through terror.

But it didn’t work.

When Brandreth was executed at Derby Gaol on 7 November 1817, his decapitated head was shown to the crowd of citizens outside.

They were now supposed to cheer the execution of a traitor. That was the convention.

But instead, the execution was met by an eery, mournful silence. Jeremiah Brandreth had been one of their own.

Similar crowds to the one in Derby would be at

Peterloo in Manchester two years later to demand votes for the working class. Soon after that, they would be the foot soldiers of Chartism in Britain.

That’s because Jeremiah Brandreth was no anomaly.

Brandreth’s Pentrich Revolution marked the beginning of a new century of working-class struggle in Britain, for democracy and prosperity.