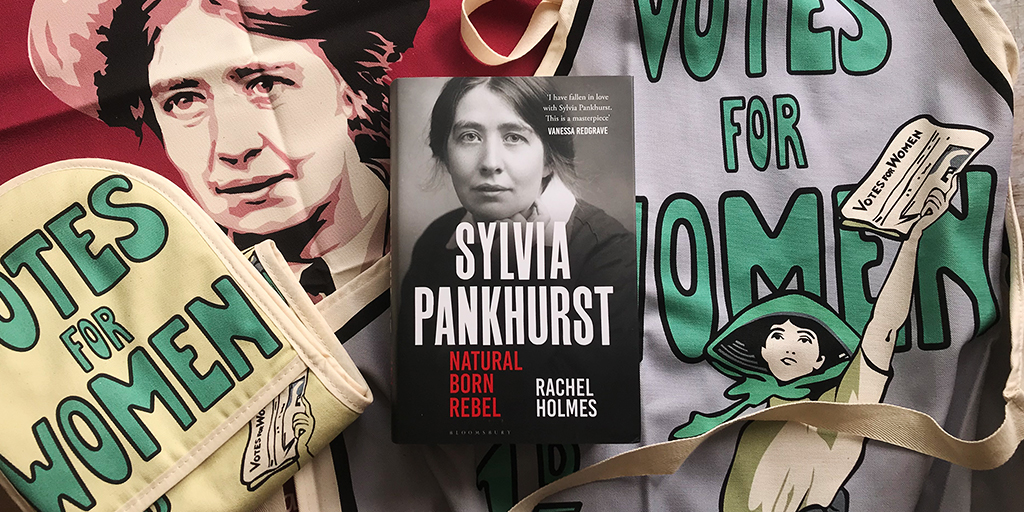

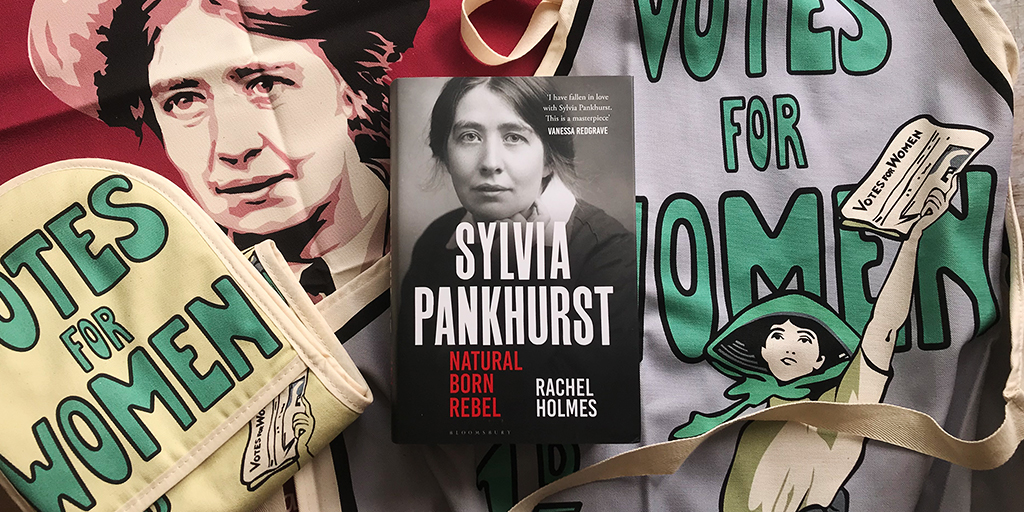

The Rebellious Life of Sylvia Pankhurst: a Q&A with Rachel Holmes

Posted by Luke on 23rd Sep 2020

We recently had the opportunity of doing a 'virtual interview' with Rachel Holmes, author of a new biography on Sylvia Pankhurst ('Sylvia Pankhurst: Natural Born Rebel', published September 2020 by Bloomsbury). She gave us a preview of what to expect inside her new book about this incredible progressive champion, whose involvement in radical campaigns stretched from the Suffragettes to anti-colonial movements of the mid-20th century.

1. Have you been able to find anything about Sylvia's upbringing which sent her on such a different ideological course to others in the Pankhurst family?

Ah, yes, a great deal! I dive deep into exploring this important question throughout the book.

All the Pankhursts were first and foremost socialists. I tell the story of how and why Sylvia’s mother Emmeline, her elder sister Christabel and her younger sister Adela set off on such a different ideological course from the principles of socialist feminism from which Sylvia never diverged. As I say in the preface, ‘All civil wars begin in the family. Personal political tragedy sits at the heart of Sylvia’s story.’

2. To what degree was Sylvia conscious of the pre-WSPU and pre-Labour Party radical political movements of the 18th and 19th centuries? Did she see herself as the heir to a much wider historical struggle, or at the vanguard of a new movement in early 20th century society?

By introducing the reader to both the Pankhurst and Goulden ancestors, I show how these much wider historical struggles were in Sylvia’s DNA – on both sides of her family she was descended from Chartists, abolitionists, women’s rights activists, republicans and democratisers.

One of the many fascinating aspects of working on Sylvia’s own writing, which I present extensively and in detail in my book, was to spend time reading her work on the Chartists, anti-racist abolitionist movements and early feminist movements, in Britain and further afield, including the USA, Scandanavia, Germany and India. Of course, her beloved father Dr Richard Pankhurst was part of the pre-WSPU and pre-Labour Party radical political movements – he drafted the Married Women’s Property Act with his friend John Stewart Mill and helped with wording the early petitions for votes for women.

Sylvia came to consciousness shaped by those early political movements, growing up in Manchester – the radical capital of Britain. Sylvia’s essays about Mary Wollstonecraft, for example, are brilliant, and much overlooked until now. One of my particular favourites is her piece on Mary Wollstonecraft and education. As an internationalist, she always has a wider view: her knowledge of and writing about international feminists and socialists is a through line of my book, whether it be the early Scandanavian feminists, Rosa Luxemburg or Harriot Stanton Blatch – who was something of a mentor to her.

3. Why the interest in Ethiopia in particular, given that fights against fascism were taking place elsewhere closer to home at the time, for example in Spain?

This is exactly the question I answer in the second half of my book, which focuses on Sylvia’s post-suffragette life from 1924 to her death in 1960. The struggle for Ethiopian independence was the work of thirty years of Sylvia’s life, and the one which she said gave her the greatest pride. Up until now it is the part of her life that has received the least attention, an imbalance I aimed to correct in my biography.

Sylvia showed how everything was connected. Geo-politically, Ethiopia is as close to home as Spain. I show in the book how the Italian-Ethiopian war was a very local question of concern about nationalism and imperialism for British people. For Sylvia, nothing was closer to home than the fight against Mussolini and his pupil – as she warned – Hitler, which began in Ethiopia (then known as Abyssinia) and then later spread to Spain. Her partner and soulmate Silvio Corio was an Italian political exile, their son Richard was of course British-Italian, their friendship circles and political milieu in London were predominantly Italian and African exiles and immigrants. Her home in Woodford, known as ‘The Village’ was a hub of emerging young African political leaders, studying or exiled in Britain, who went on to become presidents and leaders of their liberated post-colonial nations. Sylvia’s newspaper The New Times & Ethiopian News devoted extensive coverage to the Spanish Civil War, and equally to the struggle against the rise of right-wing extremism in Britain and Mosley’s fascist thugs and the BUF. Sylvia pointed out in her editorials and campaigning the element of racial prejudice in how some people in Britain and the USA paid more attention to Spain because Spanish people were regarded as western Europeans rather than black Africans.

As I show in the book, Sylvia was warning about the rise of fascism as it was emerging in Mussolini’s early hostilities against Ethiopia from the outset, whilst Winston Churchill, the elite and the British monarchy were praising Mussolini for making the trains run on time. She warned that the racist, imperialist Italian-Ethiopian war must be opposed by Britain, for if Mussolini were allowed to colonise Ethiopia, supported by western European governments including Britain, western Europe would be next. She was of course – devastatingly – proved right.

4. Do you think Sylvia had any significant regrets at the end of her life?

Sylvia was too busy working to ever have any significant regrets. One of the many delights of living with her as a biographer is to be in the company of a such an influential political woman who lived her incredibly busy life to the absolute full. She had only one single significant regret towards the end of her life: that she had to give up her artistic vocation. Rita Pankhurst, her daughter-in-law, told me that Sylvia took a set of new paintbrushes with her when she emigrated to Ethiopia in her seventies, in the hope that she would have time to paint. But, typically, she was still so busy campaigning that the brushes remained untouched. One of my most cherished objectives in this book was to tell the story of Sylvia’s artistic gifts and career from her earliest childhood, and to try and do justice to recording the story of her exceptional talent.