The Tolpuddle Martyrs: Six Farmhands from Dorset Banished to Australia

Posted by Pete on 18th Mar 2018

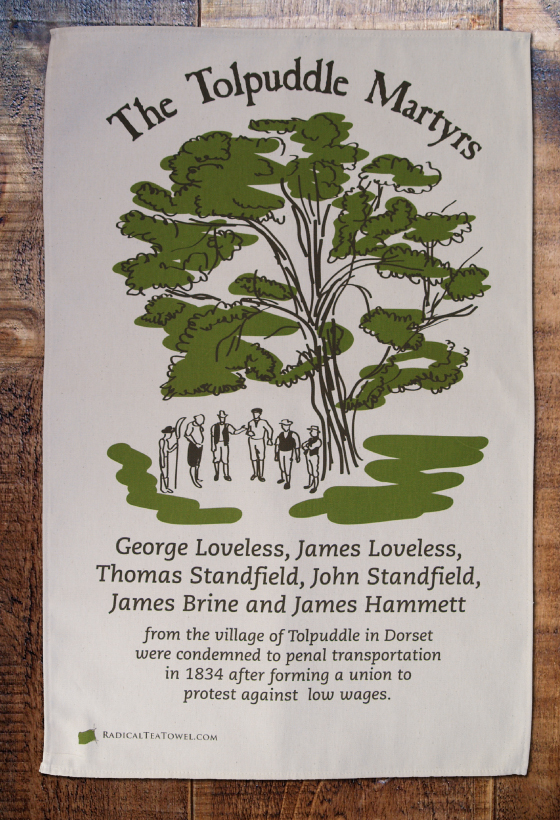

George Loveless, James Loveless, Thomas Standfield, John Standfield, James Brine, James Hammett. Listed like that, you probably haven't heard of these men.

But they have another name you will know – the Tolpuddle Martyrs.

In 1833, these six farmhands from Tolpuddle in Dorset formed the 'Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers' – a trade union.

The Dawn of Trade Unions

A decade earlier, unionisation had been effectively legalised in Britain with the repeal of the 'Combination Acts', and so the Tolpuddle men decided to make the most of this new space for action.

They formed their Friendly Society and, as a group, refused to work for less than 10 shillings a week at a time when farm wages were slipping as low as 6 shillings.

Though British law now approved this kind of industrial action, the British ruling-class didn't. They would try whatever they could to stop workers from acting together for better conditions.

Soon enough after the Tolpuddle Friendly Society had been set up, a local Dorset landowner wrote to the Home Secretary demanding action against the farm labourers.

From Peterloo to Tolpuddle, the Chartists to May Day 1895 - 19th century workers' movements

A familiar anti-union pushback

Resorting to an obscure piece of legislation aimed at Navy mutineers, the state was able to convict the six men because they had formed their union by the act of taking a secret oath.

On 18th March 1834, they were all banished to Australia to do seven years of penal servitude.

But, even though they were on the other side of the world slaving away in the heat of the south Pacific, the British people would not forget their 'Tolpuddle Martyrs'.

A petition for their pardon was signed by no fewer than 800,000 people, and a large march was organised in London – possibly the first successful march in the history of British protest.

Seeing that the people would not stand for their government shamelessly and illegally siding with landed gentry, the Home Office backed down. The Tolpuddle Martyrs were pardoned and, by August 1839, all of them were safely home.

After five years of abuse by the state and the capitalists, their trials were over.

But the trials of organised labour in Britain were not.

The pardon of the Martyrs ensured respect for the basic right to unionise (for a time, at least), but that was not final victory for the workers. Social justice had not been achieved.

You needn't do more than a quick scan of our post-1839 tea towels to see that there were still battles to be fought and won.

From unionisation to a labour movement

Keir Hardie realised that trade unions needed a political arm – a Labour Party – to give them some real social muscle.

The great internationalist, Rosa Luxemburg, saw the need to connect the workers across national borders if they were going to be able to beat capitalists who were organised internationally.

And the 1984 Battle of Orgreave, along with the wider war that Margaret Thatcher waged against the British trade union movement, serves up a painful reminder that gains can always be undone by a determined right-wing agenda.

All this being said, the Tolpuddle Martyrs are undeniably a victory to celebrate.

Their courage and that of the hundreds of thousands who backed them inflicted a great defeat on unregulated capitalism.

While the fight for workers' rights continues, who's to say we can't enjoy the liberation that comes from celebrating the struggle? Enjoyment, for example, in the memory of six men who did the simple but fearsome thing of coming together to achieve a freedom they could not have achieved alone.

As George Loveless - the Methodist preacher who led the union – scrawled down on a scrap of paper as they were sentenced to exile:

We raise the watch-word liberty;

We will, we will, we will be free!