Abd el-Krim: The Che of the 1920s

Posted by Pete on 6th Feb 2024

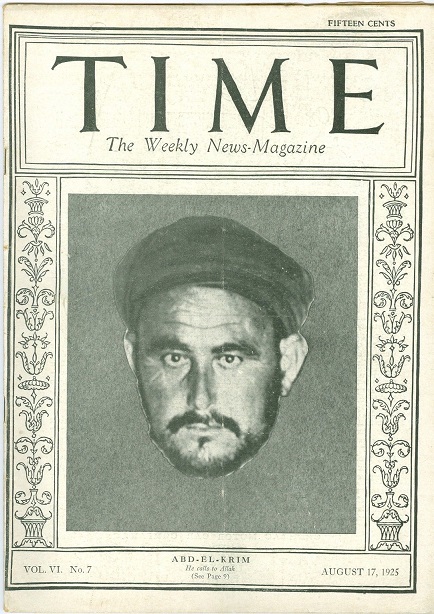

Abd El-Krim, who died on 6th February in 1963, made it to the cover of Time magazine and showed that European empires weren't invincible

The world-renowned Abd el-Krim on the cover of Time magazine in 1925

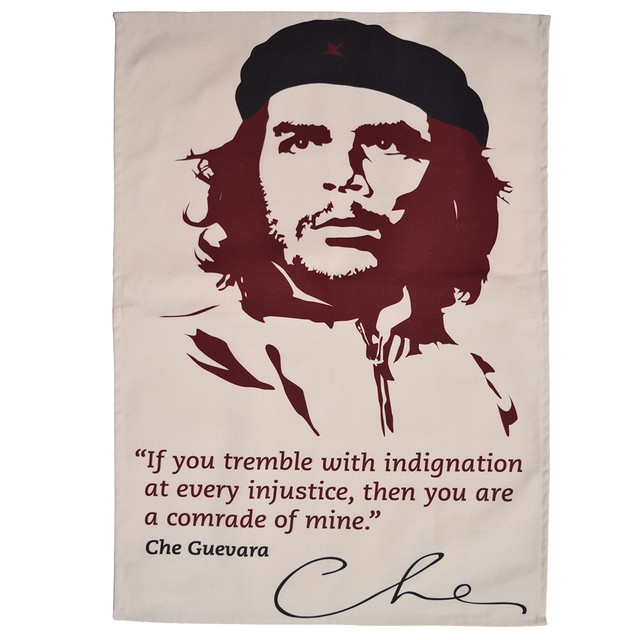

Abd el-Krim was the Che Guevara of the 1920s – and Che Guevara knew it.

During and after the Cuban Revolution, Che saw Abd el-Krim as a model of anticolonial resistance.

But Abd el-Krim wasn’t from Latin America. He was a Moroccan. And for a few years during the 1920s, he brought what was left of the Spanish empire to its knees.

Third world revolutionaries like Che Guevara were inspired Abd el-Krim's attempt to liberate Morocco in the 1920s

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Karim al-Khattabi belonged to a Berber family from Ajdir, on the north coast of Morocco.

He was born in 1882 or 1883, and grew up under Spanish rule.

Since the independence of mainland Latin America at the start of the nineteenth century, and then the loss of Cuba and Puerto Rico in the 1890s, Morocco was Spain’s last major colony.

The indigenous Berber and Arab population was lorded over by an often violent, military regime.

For a while, Abd el-Krim worked with the Spanish colonial government.

After going to university in Fez, he worked in the town of Melilla as a teacher and translator for the Spanish authorities there.

During the First World War, in which Spain was neutral, el-Krim was promoted to chief qadi – a judicial post – of Moroccans in Melilla.

But his relations with Spain began to sour when France began calling for his arrest.

The French empire had a big role in Spanish-ruled Morocco. France ruled over the eastern part of the country, and there was a lot of contact between the two colonial powers.

In this context, Moroccan sympathy for the Germans – inspired by Germany’s alliance with the Ottoman empire – angered France.

Abd el-Krim’s family included prominent critics of France and its allies, and the Spanish government agreed to imprison him in 1916.

He escaped in 1918, then went home to Ajdir.

Convinced that Spain could no longer be trusted by Moroccans, Abd el-Krim launched an anticolonial war of independence.

Defeat was a real possibility for colonial powers such as Spain and France - Toussaint L'Ouverture's Haitian revolt in the late 18th century had shown the threat of even highly suppressed slaves

See the Toussaint L'Ouverture tea towel

Abd el-Krim declared an independent ‘Republic of the Rif’ and demanded that Spain leave Morocco.

But the Spanish government was unfazed.

Seriously underestimating Moroccans’ will to fight against colonialism, Spain tried to crush Abd el-Krim’s rebellion.

In 1921, 60,000 Spanish troops moved to confront Abd el-Krim. It took him only a few months to defeat them.

A series of lightning cavalry strikes and guerrilla raids by the Rif forces drove the Spanish back.

By 1924, Abd el-Krim’s outgunned rebels had pinned down the Spanish army in a few coastal towns. He had liberated most of Morocco.

But then France stepped in.

The French empire was altogether more powerful than its Spanish neighbour, and when Abd el-Krim extended his liberation campaign into French territory in April 1925, France responded with overwhelming violence.

A combined Franco-Spanish army of 250,000 soldiers was sent to crush the Republic of the Rif.

Their commander was Marshal Henri Petain, best-known for collaborating with Nazi Germany during World War 2.

In fact, plenty of fascists – French and Spanish – spent formative years fighting to crush Abd el-Krim’s rebellion in Morocco. Spanish veterans of the campaign would be key to Francisco Franco’s war against Spanish democracy in 1936.

After the French invasion, Abd el-Krim held out for another year, but the colonial forces were now too powerful to resist. He surrendered to France in May 1926.

Abd el-Krim had become world-famous as a symbol of anti-imperial resistance during the 1920s.

The Moroccan was celebrated all over the world – in Mexico, China, Peru, India – for taking a stand against European colonialism.

And even in defeat, Abd el-Krim continued to give active support to anticolonial movements.

He lived until 1963, first in French exile, then in Nasser’s Egypt.

During those decades, Abd el-Krim championed movements for Arab liberation, including the Algerian war of independence against France. He also corresponded with Ho Chi Minh, advising the Vietnamese leader on how best to wage an anticolonial war against French rule.

He even lived to see the eventual independence of Morocco in 1956, but refused to go home before French forces had left all of North Africa.

Half a century after the fall of the Republic of the Rif, Third World radicals like Che Guevara continued to look back to Abd el-Krim’s war of independence as a model of resistance.

Abd el-Krim may not have won independence, but he had shown that European empires weren’t invincible.

Decades later, from Algeria to Vietnam, colonised peoples continued to draw inspiration from the Moroccan struggle of the 1920s.