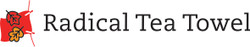

Common Decency: Albert Camus and Moral Choices

Posted by Pete on 7th Nov 2020

Born today in 1913, Albert Camus tried to place morality above all else.

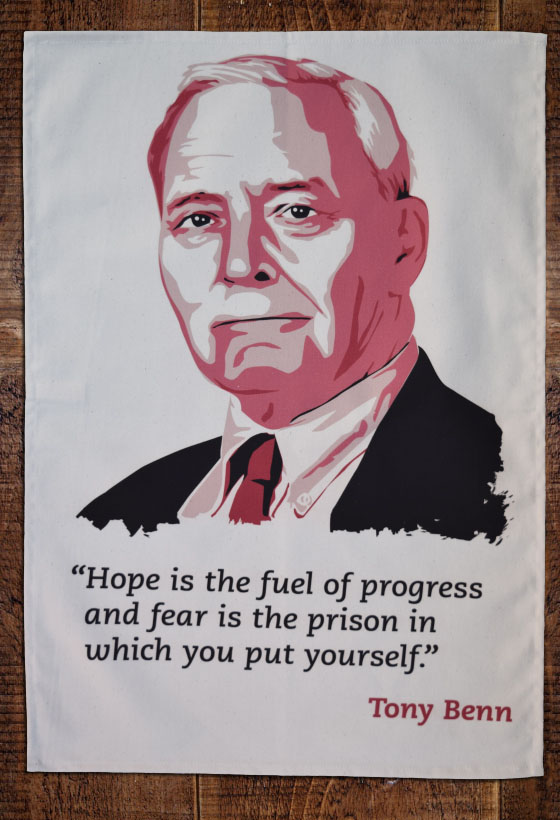

The legendary British socialist, Tony Benn, once said that.

Albert Camus (1913-60) would have agreed.

Author of The Plague, The Stranger, and The Fall, the French-Algerian writer – an intellectual grandee of the 20th century – consistently held that politics is a matter of morality.

When he was writing for the French Resistance during the Nazi occupation, for instance, he declared,

Born in Oran, today in 1913, Albert Camus came from the poorer section of the white settler population in French-occupied Algeria.

He was raised by his mother alone – his dad having been killed in the Great War.

Albert had a formidable mind, which he devoted to literature and philosophy. He learned in the French university system but also, interestingly, on the football pitch.

A talented goalkeeper, he once wrote,

A budding intellectual and journalist, Camus briefly joined the French Communist Party (CPF). Though not a Marxist like many of his colleagues, he saw the organisation as a means to fight against inequality and exploitation in contemporary France – a sort of moral crusade.

Camus worked to promote working-class culture and theatre, and he supported a wave of industrial action which swept France in 1936.

When war broke out with Nazi Germany, Camus tried to enlist in the French Army but was refused on the grounds of tuberculosis, which he had suffered with since his teenage years.

Camus was still able to serve the anti-fascist cause – at great personal risk – by using his journalistic skills writing for Combat, a major newspaper of the French Resistance.

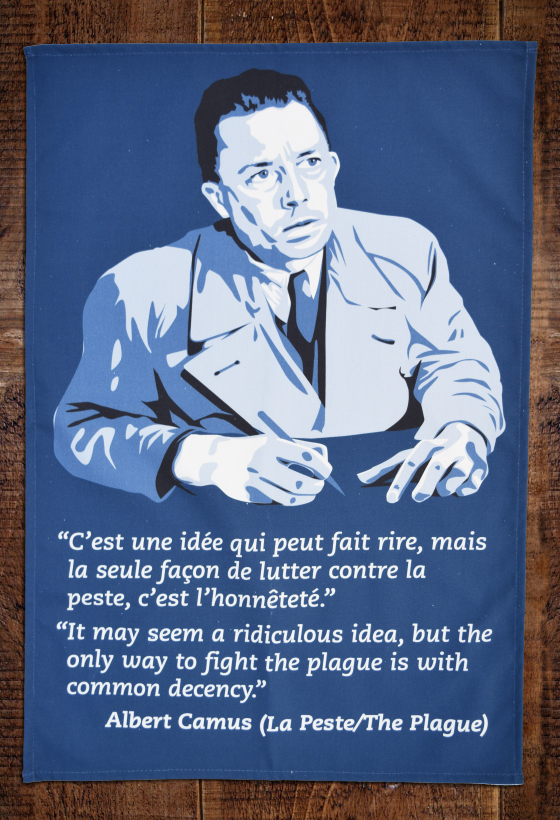

After the war, echoing George Orwell, Camus took up a left-wing anti-totalitarian stance in the new, Cold War world.

His criticism of unfreedom in the USSR cost him some good friends on the French Left, but unlike many who claimed to be against totalitarianism at the time, Camus also had the moral consistency to oppose the fascist friends of the West as well.

A devoted enemy of Francisco Franco since the Spanish Civil War began in 1936, Camus quit UNESCO in protest when the body admitted Fascist Spain as part of its wooing by the United States.

But to live morally – to take the moral path – can be difficult, even for Camus.

The great misstep of his life was his refusal to condemn outright the increasingly brutal colonial government in Algeria.

While he had long called for limited improvements to the treatment of the indigenous majority, his loyalty to the colonial regime never broke.

When the Algerian people rose en masse for independence in the 1950s, Camus did not give his voice to their cause like Jean-Paul Sartre had.

The open torture being practised by French paratroopers, the increasing barbarity of the colonial state, the blatant will of the Algerian masses – none of this was sufficient to change Camus’ position.

Rooted as it was in his personal background as a Pied-Noir – a white settler – the issue of Algeria was a pain in Camus’ soul, tearing him between his morality and his identity. He compared the feeling to the physical pain of tuberculosis.

Camus never reached the moral path through the Algerian Question, dying in a car crash in 1960.

Doing what is moral is not easy. All kinds of things – identity, loyalty, politics – can make it difficult to know what it is, and difficult then to do it.

Camus’ life and thought shows us this in the courage it took for him to do the right thing – both when he managed to and when he didn’t.