We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

Radicals on Trial: Tom Paine's Rights of Man

How one pamphlet infuriated the entire British establishment

Long before the House Un-American Activities Committee in the US, there was the trial of Thomas Paine in England.

But in the 1790s, the spectre haunting the British Establishment was republicanism, not socialism.

Aristocratic nightmares were filled with thoughts of France, where the people had stormed the Bastille and thrown off the chains of absolute monarchy in the name of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Fearing the spread of this project across the Channel, the British elite went to war on the French Revolution and its values.

But this war was not confined to foreign battlefields – not at all.

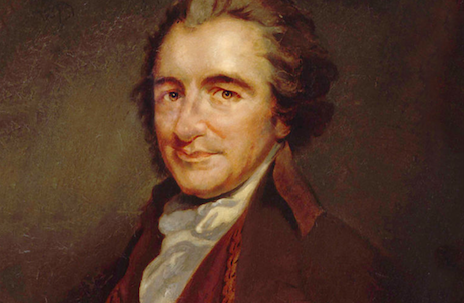

Often considered one of the founding fathers of the US, Thomas Paine's political writings galvanised the revolutions of his age. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The Tory government of William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806) waged an all-out war on dissent, reformism, and simple free speech in Great Britain itself.

This persecutorial frenzy chose Tom Paine (1737-1809) for its first target, the most famous English radical of the age.

Originally from Norfolk, Paine had been a lead protagonist on the side of the American revolutionaries in their fight against the British Crown (1775-83).

Since then he had returned to England, where he happened to be when the French Revolution broke out in 1789.

It was against this backdrop that Paine's most famous pamphlet Rights of Man was written – the first part of which was published on this day in 1791.

Click here to view our Thomas Paine tea towel

This was his answer to the so-called 'Revolution Controversy' which had been raging in England since the storming of the Bastille.

It was sparked by Edmund Burke's attack on the radical clergyman, Richard Price, over the latter's support for the French revolutionaries.

Burke's rant, Reflections on the Revolution in France, has since become the sacred text of British conservatism.

At the time, it provoked a literary counter-offensive by some of the most formidable minds in England, including the great radical, Mary Wollstonecraft.

Tom Paine's Rights of Man was his personal contribution to this wave of radical literature.

"When it can be said by any country in the world, 'my poor are happy, neither ignorance nor distress is to be found among them, my jails are empty of prisoners, my streets of beggars, the aged are not in want, the taxes are not oppressive, the rational world is my friend because I am the friend of happiness.' When these things can be said, then may that country boast of its constitution and government." - Thomas Paine, Rights of Man

Paine made a defiant argument for the right of people to rid themselves of an oppressive government, setting out a range of reforms which would help eliminate the poverty and economic inequality then endemic in England.

Mary Wollstonecraft was another writer who weighed in on the French Revolution 'Pamphlet War', writing A Vindication of the Rights of Men in response to Burke.

Click here to view our Mary Wollstonecraft tea towel

The pamphlet was an instant, massive success. It had soon reached over a million readers, many of them working-class.

Its pages are full of witty rebuffs and fiery one-liners: "It is power, and not principles, that Mr Burke venerates," he writes at one point.

And in a cogent argument against monarchy, he writes: "If I ask the farmer, the manufacturer, the merchant, the tradesman, and down through all the occupations of life to the common labourer, what service monarchy is to him? He can give me no answer."

The pamphlet was so successful that William Pitt's government decided to supress it.

Paine’s publisher was indicted for "seditious libel" – a crime based on the archaic notion that the government is beyond criticism – and Paine's own indictment soon followed.

But the authorities were too slow to catch Paine. He had already moved to France, where the revolutionaries had elected him to their National Convention.

Nonetheless, Paine was tried in absentia. Pitt's government had a point to prove: no radical or reformist opinion would be tolerated anymore.

Surprise, surprise, Paine was convicted and sentenced to hang. Thankfully, though, he managed to live out the rest of his life abroad, never returning to England where Pitt's executioners awaited him.

What's worse, this Kangaroo Court paved the way for countless more arrests and convictions throughout the 1790s and well into the 19th century.

In a certain 'polished' version of history, England emerges from the years of the French Revolution and Napoleon as a bastion of liberal tolerance.

But, as Rosa Luxemburg said, "freedom is always the freedom of dissenters." And such freedom was non-existent under the iron aristocracy of Pitt and his successors.

Perhaps, then, the true heroes of this era were those who persisted in the fight for democratic rights and equality regardless of the threats and persecution. Those radicals, like Tom Paine, who struggled for a new Britain: dignified, equal, and free.