Socialism With a Human Face: Alexander Dubček and the Prague Spring

Posted by Pete on 5th Jan 2022

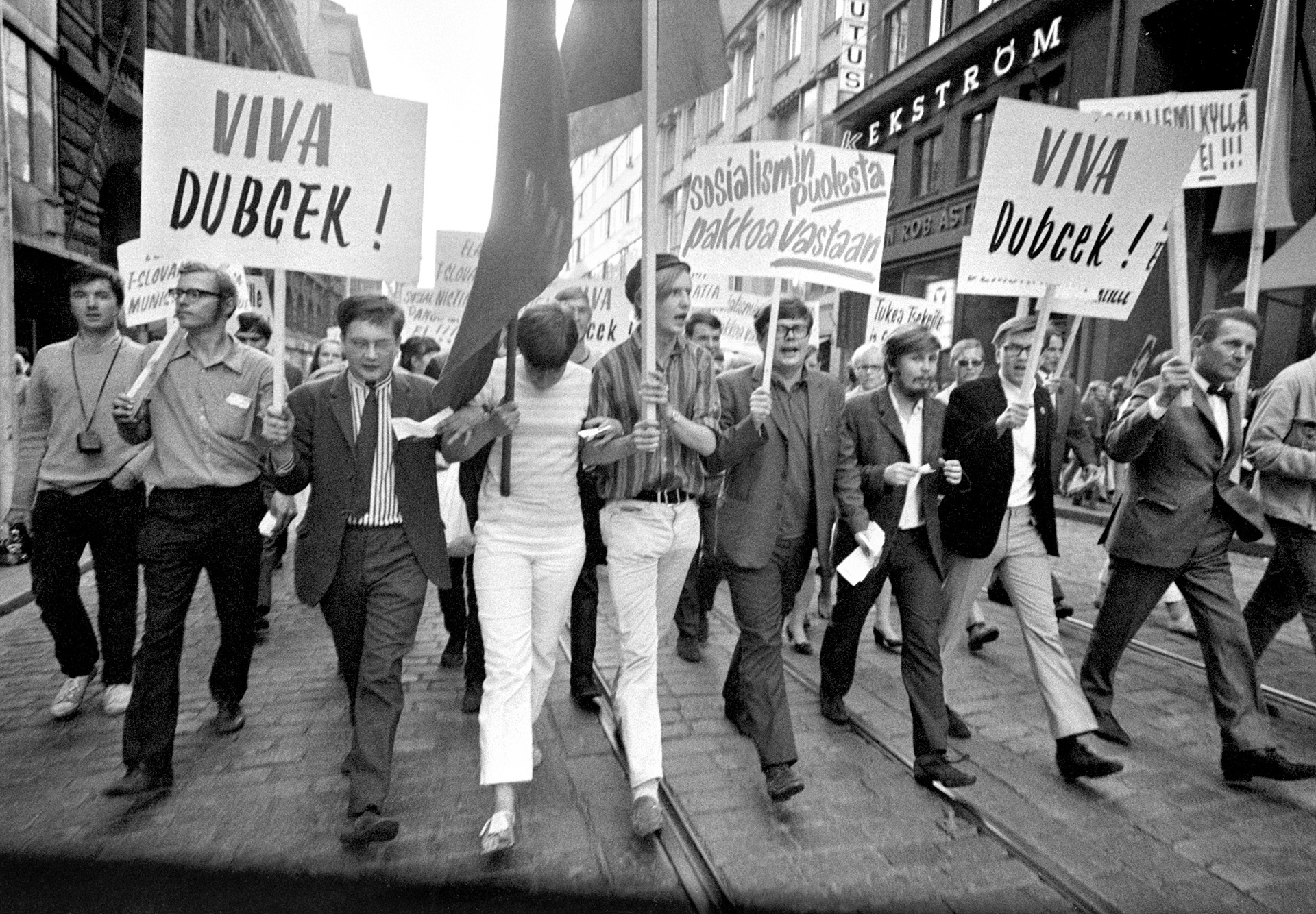

The story of how radicals in Czechoslovakia tried to democratise Soviet rule

It’s not often that Spring begins in January…

But that’s exactly what happened in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in 1968, when Alexander Dubček became – mouthful alert – First Secretary of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

After two decades of Soviet-style Communist dictatorship, the arrival of Dubček began the “Prague Spring.”

But first, a bit of background. In 1948, three years after Czechoslovakia had been liberated from the Nazis, the country’s Soviet-backed Communist Party launched a coup.

For the next few years, the country suffered horribly under Stalinism.

Many pro-democracy movements harked back to the legacy of Rosa Luxemburg and her anti-dictatorial theory of Marxism.

Click to view our Rosa Luxemburg tea towel

Then, after Stalin’s death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev came to power in the USSR and launched a limited reform project, meant to reduce state repression in the country.

Czechoslovakia, then ruled by Antonín Novotny, followed Khrushchev’s lead, albeit more slowly than the rest of the Soviet Bloc.

Things began to change, ever so slightly.

Victims of earlier purges were rehabilitated, and the centralisation of the economy was loosened.

In this atmosphere of cautious reform, ordinary citizens of Czechoslovakia began to test how far they could go in pursuit of more freedom.

Intellectuals challenged state censorship, celebrating the Prague-born Franz Kafka, whose novels had been a favourite target of Communist Party censors.

But things began to open up much quicker when, on 5 January 1968, Alexander Dubček became First Secretary.

As First Secretary, Dubček attempted widespread democratisation of the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia.

A reformer from the Slovakian wing of the Communist Party, Dubček was intent on re-establishing political freedom in Czechoslovakia.

In February, the Union of Czechoslovak Writers was allowed to publish its journal,

Literární listy, without censorship. By August, it had a circulation of 300,000 – the largest in Europe.

Then, in April 1968, Dubček launched a more comprehensive set of reforms.

This ‘Action Programme’ increased freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and freedom of movement.

The power of the secret police was reduced and the idea of multi-party government was put forward.

But, as was often true of reform and resistance movements in the Soviet Bloc, the Prague Spring was neither a rejection of socialism nor an embrace of capitalism.

Dubcek and much of his support in Czechoslovakia were socialists, they just wanted a different socialism to the top-down, authoritarian model enforced by Moscow.

The stated goal of the Action Programme was:

“to build an advanced socialist society on sound economic foundations… a socialism that corresponds to the historical democratic traditions of Czechoslovakia.”

But the fate of this “Socialism with a Human Face” in Czechoslovakia would not be decided in Prague. It would be decided in Moscow.

21 years after Dubček's Prague Spring came one of the most symbolic moments in history: the Fall of the Berlin Wall.

Click to view our Fall of the Berlin Wall tea towel

The post-war Soviet leadership had never been tolerant of allies in Eastern and Southern Europe having ideas of their own about the nature of socialism.

This dogmatism had driven Stalin’s crackdown on Yugoslavia and Khrushchev’s 1956 invasion of Hungary.

And now, it drove Soviet tanks across the border into Czechoslovakia.

Egged on by conservative leaders in the other Warsaw Pact countries, worried for their own position if the Prague Spring caught on, Leonid Brezhnev ordered an invasion of Czechoslovakia on 20 August 1968 – only a handful of months after Dubček had become First Secretary.

200,000 troops from the USSR, Bulgaria, Poland, and Hungary moved in overnight. Dubček ordered his people not to resist – the odds were hopeless – and Czechoslovakia was fully occupied by the end of the next day.

The Prague Spring was over.

Dubček was allowed to live, retaining his role as First Secretary for a while. But he was powerless now.

Ominous “normalisation” was enforced by a new, anti-reformist leadership, with full censorship reimposed and all talk of multi-party democracy killed off.

With hundreds of thousands of Prague Spring supporters fleeing abroad, Czechoslovakia would not see such revolutionary politics again until 1989, when the whole Soviet Bloc

began to crumble.

But the Prague Spring endures in the radical history of the Cold War.

A moment when the people of Czechoslovakia rejected authoritarian Communism and set free their own vision of society: at once socialist, revolutionary, and democratic.