The German Peasants' War of 1524-25

Posted by Pete on 16th Feb 2025

The German Peasants' War of the early 16th century was yet another peasant rebellion on the road to European democracy

England had the Peasants’ Revolt – Germany had the Peasants’ War.

From 1524 to 1525 hundreds of thousands of peasants and serfs rebelled against their feudal overlords in Central Europe.

It was the largest popular uprising until the French Revolution.

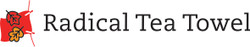

The English Peasants' Revolt was over 100 years earlier than the German Peasants' War, but was also triggered by demographic and social changes

See the Peasants' Revolt Tea Towel

Medieval Germany wasn’t, well, ‘Germany.’

Instead, it was made up of hundreds of sovereigns, some massive and some tiny, and most of them inside the loose framework of the ‘Holy Roman Empire’ ruled by the Habsburgs.

But cutting through this mess of jurisdictions was one vital continuity: class.

Throughout the region social production was done almost entirely by rural peasants, free or enserfed.

The peasantry was dominated by a hierarchy of exceedingly violent and criminal families that we tend for some reason to call ‘nobles.’

The nobility of the Holy Roman Empire came in all shapes and sizes, from Imperial Princes to small knights and feudal bishops of the Catholic Church.

But what they all had in common was the fact that they lived off the surplus produced by peasants’ labour, which the nobility extracted through layers of taxation, forced labour, and legal instruments, all kept in place by the threat of violence.

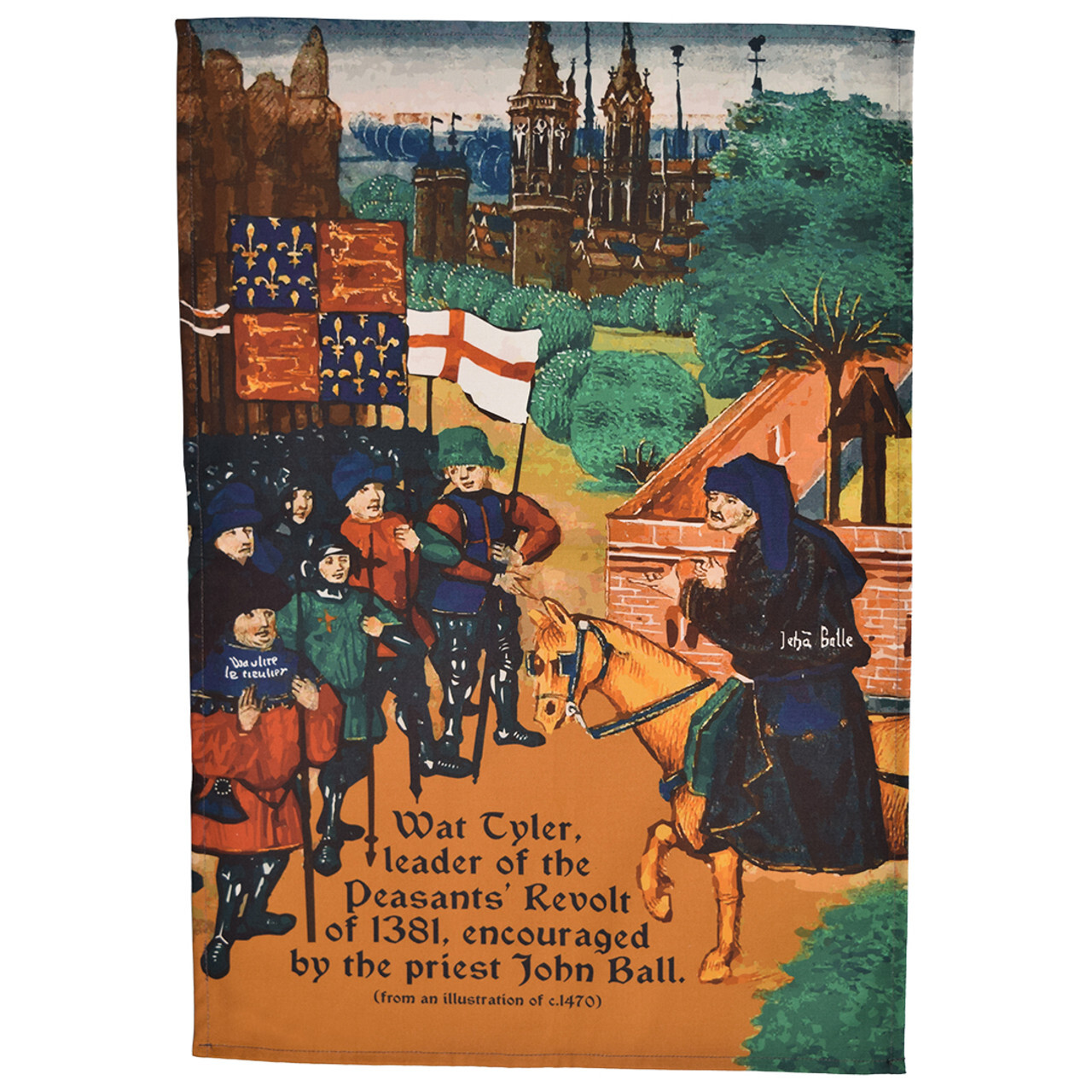

Kett's Rebellion was another medieval uprising by ordinary people fed up with the social strictures of the day

See the Kett's Rebellion tea towel

These feudal pressures constantly gave rise to acts of peasant resistance and rebellion throughout medieval Europe.

But during the 1520s, the potential for rural revolution in Germany was especially high because the Protestant Reformation had just kicked off.

Martin Luther’s condemnation of Church corruption and his demand that Christian subjects ought to be allowed a more intimate relationship with God and knowledge was exciting.

And for many peasants in Central Europe, Catholic clergymen were at the same time their exploitative landlords.

What’s more, the entire social hierarchy of the Empire was framed by the ideological authority of the Roman Catholic Church: now that authority could be questioned, so could everything.

It was a combustible situation.

Sure enough, peasants began to launch armed rebellions numbering thousands across Germany in 1524. By the end of August, most of the southwest was in revolt.

The movement was well-organised and sophisticated.

On 20 March 1525, in the city of Memmingen, peasant rebels presented a political program: the ‘Twelve Articles.’

The Articles were demands presented to the feudal ruling class, including the abolition of serfdom and a whole range of extractive taxes, as well as the democratic election of clergy by their congregations and the restoration of peasant commons which had been enclosed (stolen) by avaricious aristocrats during the past century.

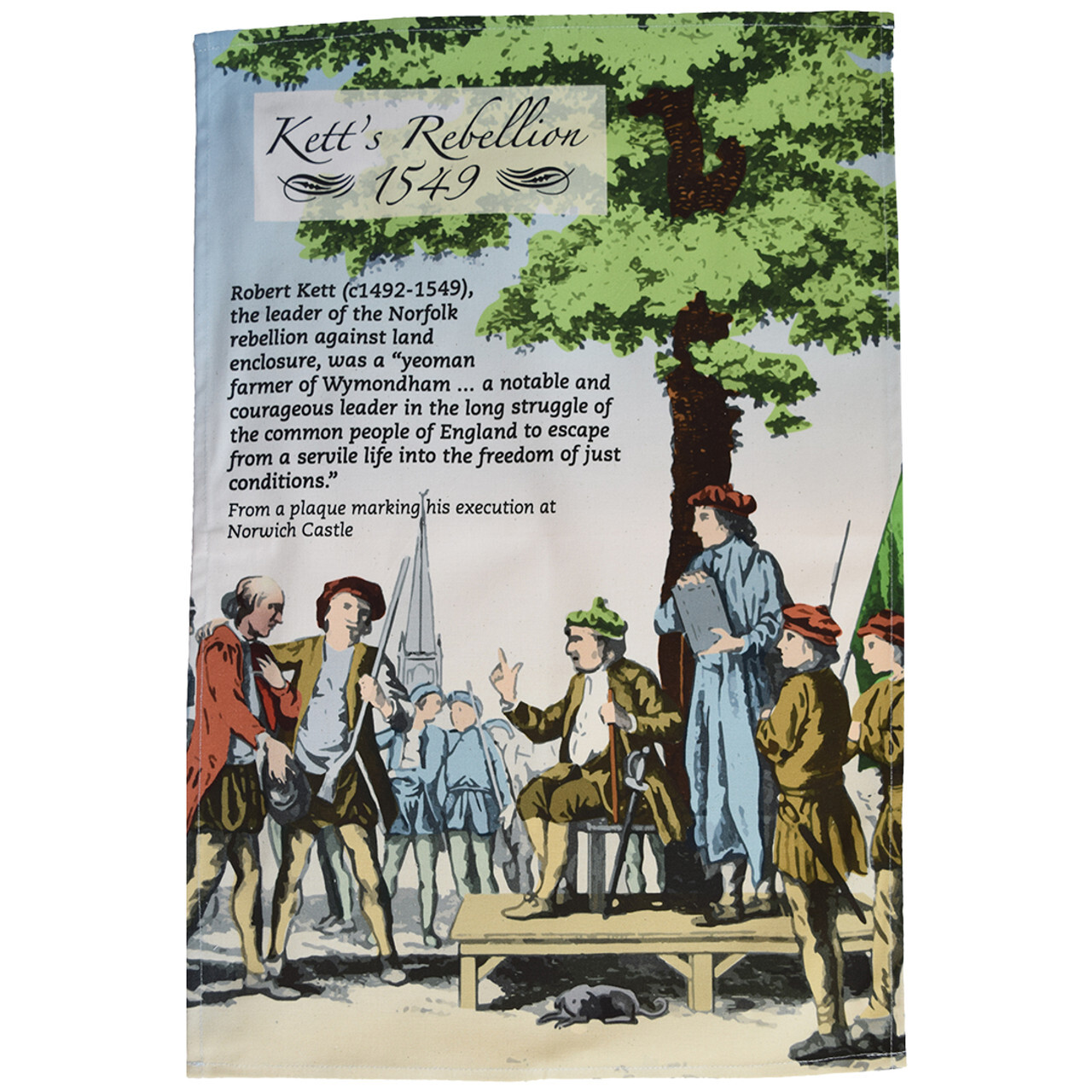

Land enclosure was a particular bugbear for populations across Europe in the middle of the last millennium

See the Enclosures Rhyme tea towel

But the nobility were, of course, barbarically ignoble.

The peasants’ demands were rejected; they would have to fight for them instead.

Some peasant rebels had military experience and they formed haufen (bands) of soldiers to help their social movement to defend itself.

The peasant army units were democratically self-governed and egalitarian, and they fought courageously in several battles across Germany.

But the German aristocracy, organised into an iron fist as the ‘Swabian League,’ were better-resourced: they had heavy cavalry and heavy artillery and they could pay for thousands of expert mercenaries.

They were also given permission by the religious authorities – Catholic and Protestant – to do their worst to defeat and terrorise the peasantry.

Despite its nominally dissenting character, mainstream Protestantism led by Luther was gaining ground among Imperial lords as a means to dodge Catholic taxes.

When push came to shove, Luther sided with this aristocratic elite against peasant rebels who were often motivated by his own theology. In fact, Luther was one of the most violent cheerleaders of the nobles’ counter revolution in Germany.

Instead, it was left to more radical Protestants like Thomas Müntzer (1489-1525) to practice what they preached in terms of equality and freedom, and side with the rebels.

Radical Reformist preacher Thomas Muentzer (c1489-1525)

But it wasn’t enough.

Although the peasant rebels across the Empire fought hard, often supported by the urban working classes of towns like Kempten and Ulm, they were defeated in most of the major battles.

And by September 1525 the fighting was over.

Tens of thousands of peasants had been massacred by manic ‘nobles’ for demanding to be treated as dignified, equal human beings. Müntzer was captured and beheaded; Luther was relieved.

But the barbaric violence of the Imperial aristocracy during the German Peasants’ War was a sign of its fear, too.

The contradictions of European feudalism meant that peasant rebellion would keep happening until, after 1789, it became too big to contain: big enough to win.