The Jewish Communist Who Fought Apartheid

Posted by Pete on 23rd May 2024

Born on this day in 1926, Joe Slovo was a key player in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa

“No matter what vision one has of South Africa, the first thing that must be done is to destroy racism.”

Joe Slovo was born today in 1926, in Obeliai, in Lithuania.

Born Yossel Mashel Slovo, he belonged to a Jewish family in Eastern Europe.

Interwar Lithuania had a deep history of anti-Semitic racism, and the Slovo family left when Joe was 8 years old.

Like many Eastern European Jews during these years – including Joe’s future comrade and wife,

Ruth First – the Slovo family emigrated to the Union of South Africa, then a self-governing colony of the British empire.

Once there, however, Jewish refugees did not find a society free from racism – they found one built upon it.

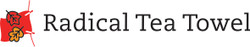

Slovo first met Nelson Mandela while he was a student activist at the University of Witwatersrand, and the two men went on to become lifelong comrades

See the Nelson Mandela tea towel

True, South Africa was much safer for Jewish people than Europe was during the 1930s, although there was plenty of sympathy for Nazism among right-wing Afrikaners.

But South Africa was, of course, a white settler colonial project sustained by the racist oppression and exploitation of the black majority of the population.

As Joe Slovo grew up in South Africa, he recognised the similarities between the anti-black racism there and the anti-Jewish racism which had driven his family out of Europe.

And Joe Slovo resolved to fight against that racism – for the rest of his life.

In 1942, Slovo joined the South African Communist Party (SACP), in which the Jewish diaspora was well represented.

Along with the ANC, the Communist Party in South Africa became one of the leading opponents of apartheid.

Another Jewish radical born in Lithuania, Emma Goldman emigrated with her family to the United States in 1885

See the Emma Goldman tea towel

Wanting to take part in the ongoing world war against fascism, Slovo joined up in the South African army, fighting against the Axis powers in North Africa and Italy.

But the experience of colonial military service didn’t dull Slovo’s radical politics one bit.

In fact, Slovo was busy agitating against South African racism from inside the army. When he returned home, he joined the so-called ‘Springbok Legion’, a multiracial veterans’ group committed to racial equality in South Africa.

After the war, during the late-1940s, Slovo got into the anti-apartheid struggle proper, just as the apartheid system was becoming more entrenched.

He studied law at the University of Witwatersrand, where he was a student activist and where he first met

Nelson Mandela.

In 1950, the apartheid regime began a severe crackdown on political dissent.

The Communist Party was outlawed – the South African government liked to dress up its racism as anticommunism, in order to give its Western allies like the U.S. and Britain a useful story to distract their own electorates – and Slovo was blacklisted.

In 1956, Slovo was arrested and detained for several months as part of the so-called '

Treason Trial', when several anti-apartheid activists were (unsuccessfully) prosecuted for publishing a Freedom Charter which called for a multiracial democracy in South Africa.

Then, in 1960, Slovo was imprisoned again – this time under the State of Emergency declared by the apartheid government after its police massacred 69 black South Africans protesting racist pass laws at Sharpeville.

At this juncture, the ANC judged that an exclusive strategy of non-violence was not working against apartheid. If anything, white supremacy was becoming more brutal, violent, and uncompromising.

So, it was decided to launch a campaign of armed struggle against the South African state, including ANC and SACP activists.

A South African bishop and theologian, Desmond Tutu rose to fame in the 1980s as a vocal opponent of apartheid

See the Desmond Tutu tea towel

In this context, Joe Slovo emerged as a key leader of uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) – “Spear of the Nation” – formed by Nelson Mandela as the armed wing of the ANC to attack government installations and the apartheid police forces.

The MK campaign was used by the South African state to intensify its political repression.

Quickly, things became too hot and Slovo had to go into exile in 1963, where he would remain for 27 years.

During that time, alongside the rest of the

anti-apartheid diaspora, Slovo kept up the struggle, even after the assassination of his wife, Ruth First, by South African secret police in 1982.

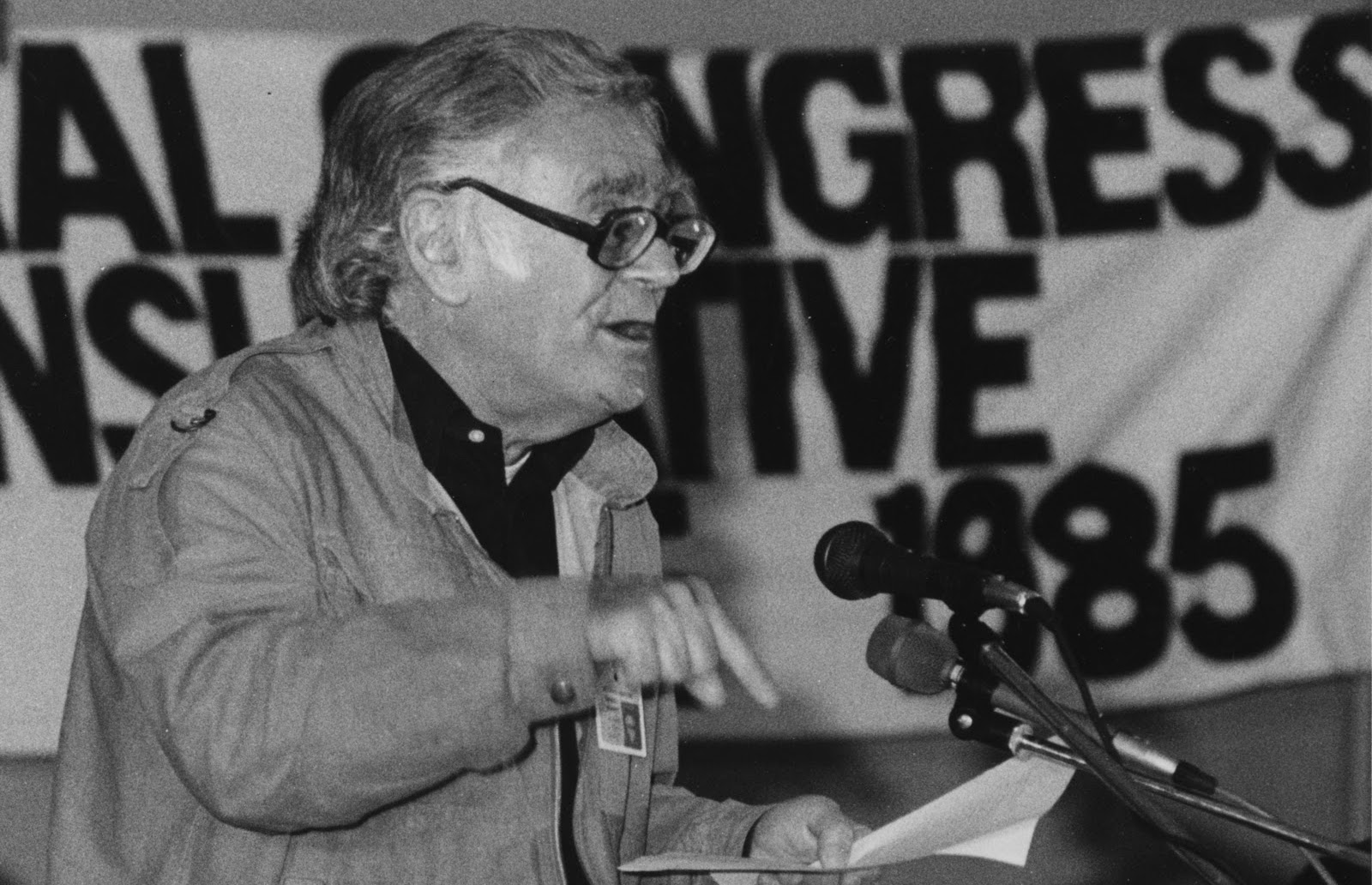

In 1984, Slovo was elected General Secretary of the SACP and in 1985 he became the first white member of the ANC Executive.

From these positions, Slovo was able to help bring apartheid to an end.

During his exile, anti-apartheid activism inside South Africa had continued, with notable events including the student

Soweto Uprising of 1976.

By 1990, with the U.S. diluting its military support for Pretoria because the Cold War was ending, the apartheid regime was near to collapse.

In that year – the year Mandela was released from prison – Slovo returned to South Africa from exile.

Alongside Mandela and other anti-apartheid leaders, he helped to negotiate the dismantling of apartheid on the basis of full majority rule, after a brief transition.

Mandela was elected President in a landslide in 1994, and he made Slovo his Minister for Housing.

Slovo died of cancer a year later; and he died as a hero of the South African people and their common struggle against racism and apartheid.