The Revolutionary Life of Auguste Blanqui

Posted by Pete on 8th Feb 2023

Born on this day in 1805, Auguste Blanqui devoted his life to the dream of revolution

“The Republic means the emancipation of the workers, it’s the end of the reign of exploitation, it’s the coming of a new order that will free labour from the tyranny of capital.”

When did the French Revolution end? When Napoleon took power? Or when Napoleon was defeated?

Well, for Auguste Blanqui (1805-1881), the French Revolution didn’t really have an end.

For him, la révolution was more than just an historical event. It was an ideal – a dream that would live on forever.

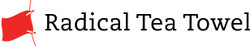

Though he was born over 15 years later, Blanqui's revolutionary life was inspired by the Storming of the Bastille in 1789

Click to view our Storming of the Bastille tea towel

Blanqui was born after the dust had settled on the first French Republic. He was a child of the Napoleonic reaction.

But France wasn’t done with republicanism. Or rather, republicanism wasn’t done with France.

The nineteenth century would see another three major revolutions, and Blanqui was involved in all of them.

He’d been born in the Alpes-Maritimes region of south-west France. His dad, who was of Italian descent, had been a republican during the 1790s.

Auguste’s turn to join the French republican tradition came in 1822.

The Bourbon monarchy had been restored in 1815. France once again had a king, but not everyone was happy about it.

An underground movement – the Carbonari – was fighting to restore the Republic.

It was the experience of seeing four Carbonari members executed in 1822 which radicalised the young Blanqui. Soon enough, he joined the movement himself.

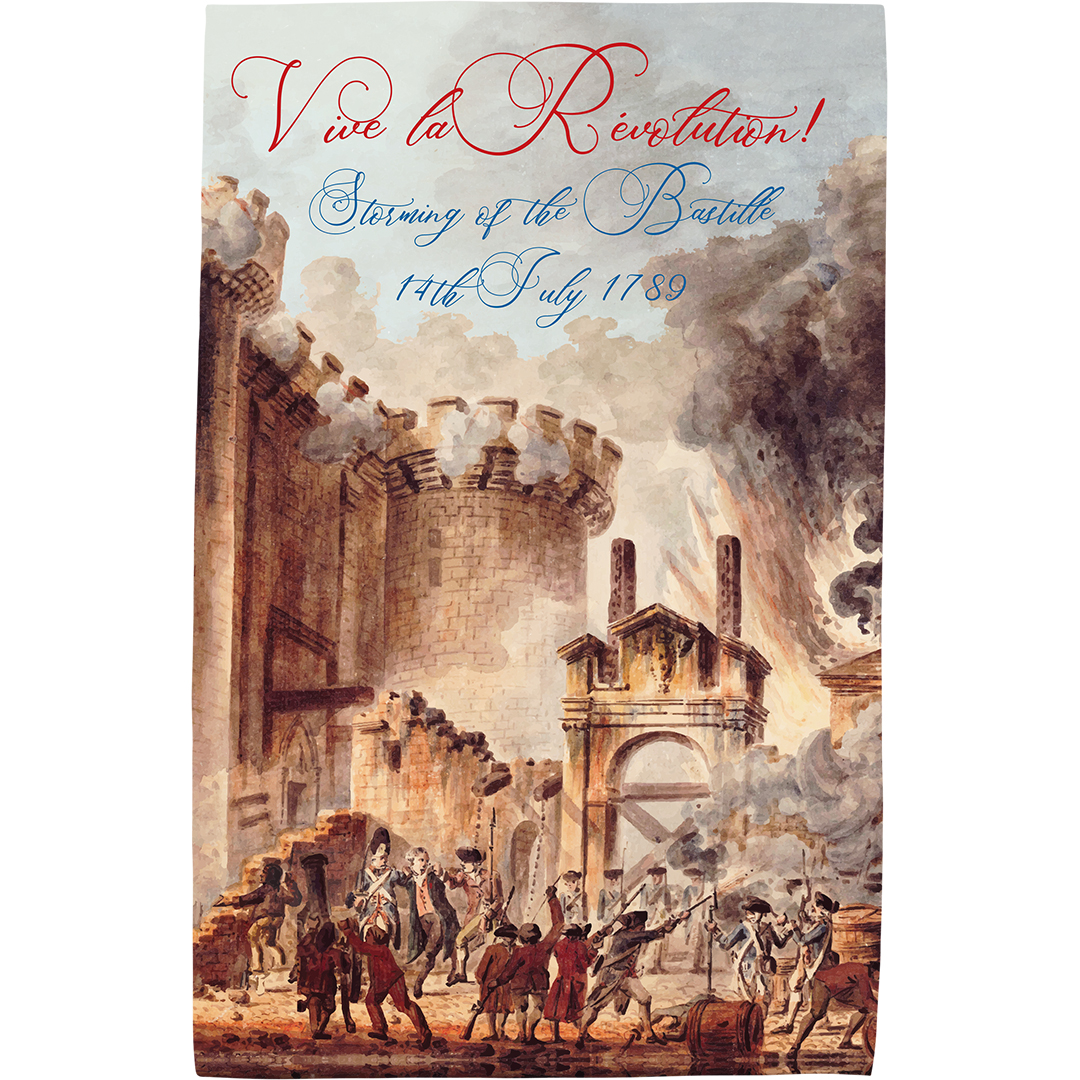

Blanqui was a leading figure in French radical circles along with Victor Hugo who called for the end of poverty in France

Click to view our Victor Hugo tea towel

He spent the rest of the 1820s in republican conspiracies, none of which seemed to come to fruition. But then came the first big opening in decades: the July Revolution of 1830.

The French had grown sick of the Bourbon dynasty (again). King Charles X was violating its meagre commitments to civil liberty and a free press.

It was time for the French people to do their thing: protests, barricades, overthrow the monarchy.

Charles X abdicated, but the monarchy wasn’t overthrown. And that wasn’t for lack of trying.

When things kicked off in 1830, there were plenty of republicans in France ready to go. Blanqui was in the thick of it, writing for the radical Globe newspaper.

The French bourgeoisie, however, had other ideas.

When they heard ‘République’ they thought of Jacobin radicalism, social egalitarianism, and the theft of private property.

So, with the help of this sector of society, Louis Philippe – the Duke of Orleans – stepped into the fray and replaced his cousin as King of the French.

Louis Philippe was much more liberal than Charles X. But he was still a pompous aristocrat. He was still a king.

Auguste Blanqui was… dissatisfied. He blamed the bourgeoisie for betraying the Revolution of 1830, and would never trust them again.

Blanqui was more and more a socialist republican, in the tradition of Gracchus Babeuf. His people were the working class, and his enemy was not just the monarchy but the capitalists, too.

In fact, Karl Marx was a big admirer. He called Blanqui

“the brains and inspiration of the proletarian party in France.”

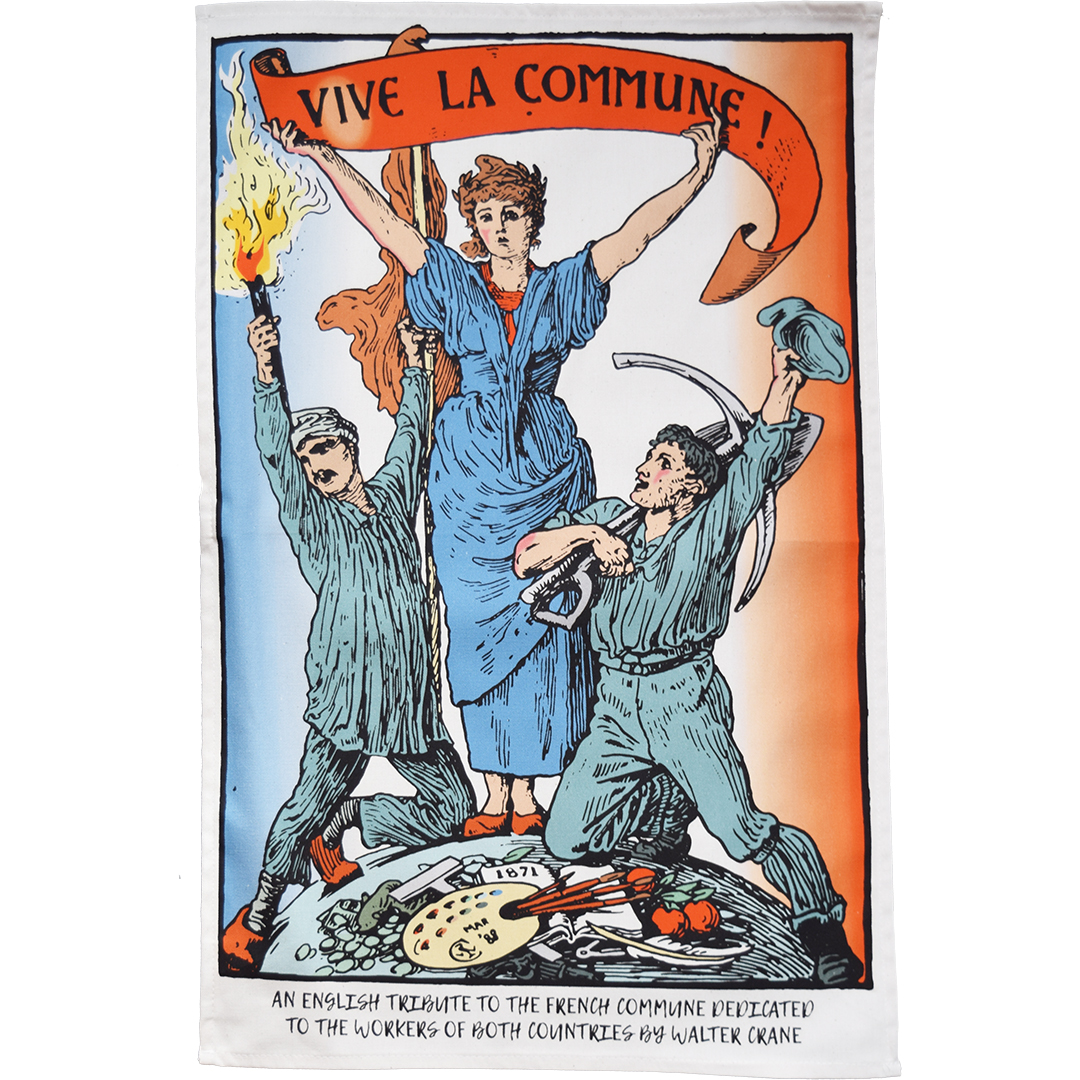

Karl Marx also said that Blanqui was the missing link in the success of the 1871 Paris Commune

Click to view our Paris Commune tea towel

Blanqui’s radical vision meant he kept agitating long after 1830.

In 1840, he was given his first long prison sentence (narrowly avoiding execution) after his ‘League of the Just’ had tried a republican uprising in Paris.

Blanqui was still in prison in 1848, when France’s second major revolution of the century kicked off.

The revolutionaries quickly set Blanqui free.

Though the Revolution of 1848 did briefly overthrow the monarchy and create a new Republic in France, Blanqui still thought it too moderate.

It wasn’t socialist enough for him. It was too dominated by the bourgeoisie and did little to change the lives of French workers.

Blanqui’s agitation for the new revolution to take a socialist turn landed him in prison, again, in 1849.

Whilst there, he missed the big socialist uprising of June 1849 – ‘the June Days’ – which was crushed by the bourgeois government.

“What shoals threaten the revolution of tomorrow? The shoals that shattered yesterday’s: the deplorable popularity of bourgeois disguised as tribunes.”

Even the diluted Revolution of 1848 was undone in 1851, when a tinpot nephew of the original Napoleon made himself ‘Emperor Napoleon III’.

Under this re-restored monarchy, Blanqui was constantly in jail. He became adoringly known as “The Imprisoned One” by French radicals on the outside.

By the time of the Paris Commune in 1871, the biggest attempt at socialist revolution in French history, Blanqui was an old man.

But he was still considered dangerous enough for the authorities to jail him (again), so that the Communards could not make him their leader.

A diehard, if ever there was one. Republican, socialist, jailbird: Auguste Blanqui.