To the Uttermost Ends of the Earth: The Nuremberg Trials

Posted by Pete on 24th Nov 2022

77 years ago this week, Nazi leaders were put on trial by Allied powers at Nuremberg...

“Powers will pursue them to the uttermost ends of the earth and will deliver them to the accusers in order that justice may be done."

Moscow Declaration on Atrocities

In May 1945, the Second World War in Europe ended. The Allies had won.

But whereas the Nazi regime was gone, those responsible for it were not. Many high-ranking Nazi Party members and German military leaders were still alive, in Allied custody.

And the question on everyone’s mind was: what to do with them?

Martin Niemöller's post-war confession was an expression of regret for his own complicity in the Nazis' rise to power

Click to view our Martin Niemöller tea towel

It was already clear that Nazi Germany had not been just another brutal dictatorship.

The liberation of the concentration camps had exposed the true realities of the Holocaust. Over the course of 1945, Allied citizens began to see the horrors of Auschwitz, Dachau, and Bergen Belsen on the newsreels.

There was a sense among the victorious Allied Powers that something needed to be done to punish the Nazi leaders. They could not be treated as conventional losers of a conventional war.

The British government suggested summary executions, and the Soviets argued for show trials of the German leadership.

After being arrested by the Gestapo and convicted in a mock trial, the members of the White Rose were executed by guillotine

Click to view our White Rose tea towel

But the proposal which won out was for a basically fair trial, presided over by Allied judges independent of their respective governments, in which the defendants would have genuine legal counsel and the verdicts would not be a foregone conclusion.

This was backed by the Americans, who already had custody of the most senior Nazi prisoners after the German surrender.

These trials would be held in Nuremberg, in Bavaria, which had been the spiritual heart of Nazism, hosting Hitler’s racist rallies through the 1930s.

The Nuremberg International Military Tribunal (IMT) of 1945-46 was unprecedented in the history of international law.

Previously, however brutal their personal conduct in war, civil and military officials could just blame their conduct on the countries they represented. There was no accountability.

But now, 21 leading Nazis were going to be charged with war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity, by an international tribunal.

And the stakes couldn’t have been higher.

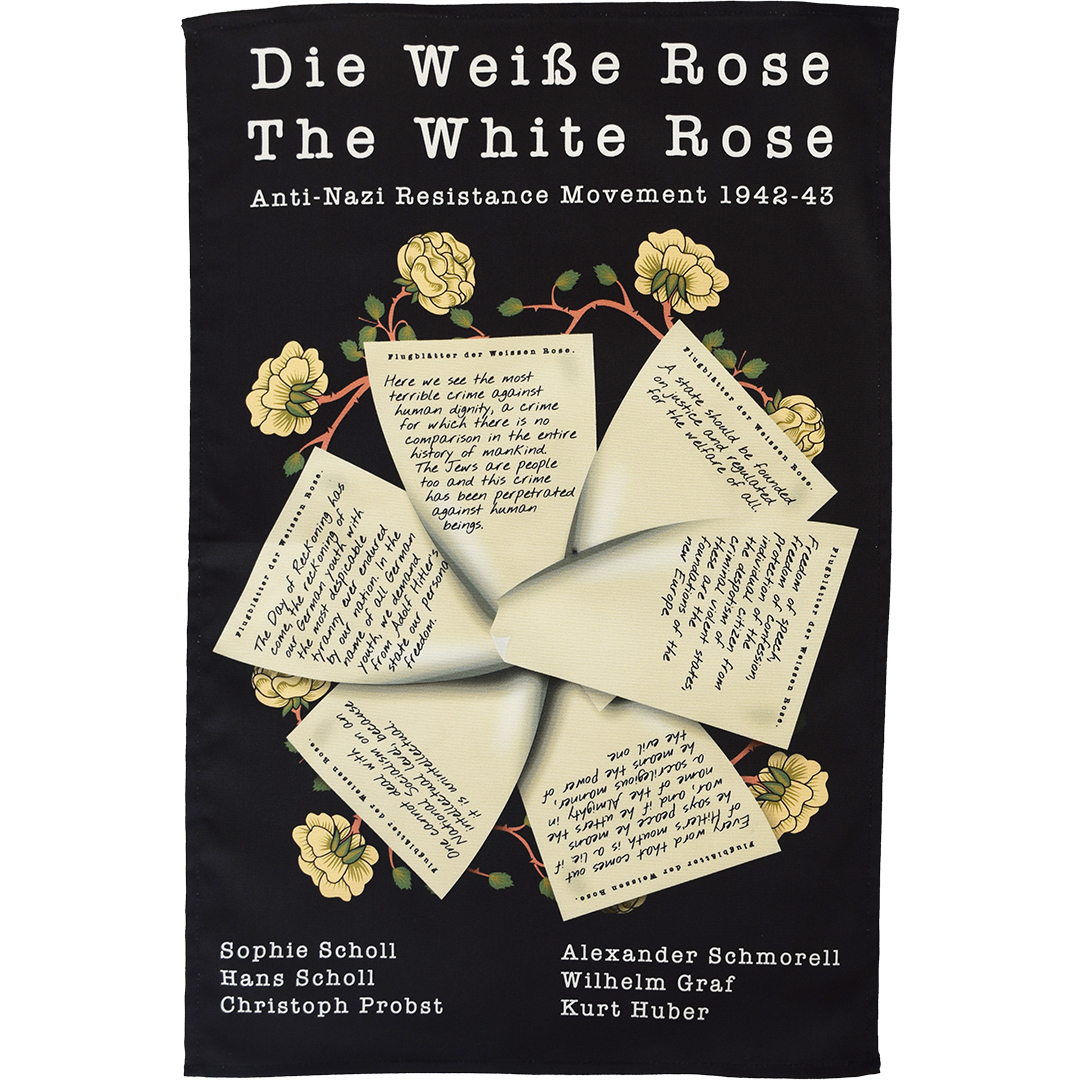

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was written up as a direct response to the horrors of WW2 and the Holocaust

Click to view our UN Declaration tea towel

In the first instance, justice needed to be served against these leaders of the Nazi regime. Hitler, Himmler, and Goebbels were all already dead. But men as senior as Hermann Göring and Joachim von Ribbentrop were still alive.

The trial was also seen as a means to convict the Nazi regime itself. Condemning the Nazi leadership in a fair trial would be an important instrument of denazification in postwar Europe.

And, if the prosecution was successful, the Nuremberg trial might create a brand new legal precedent:

international criminal responsibility. No immunity from justice because your government supported you in your crimes.

The prosecution, with lawyers from Britain, the Soviet Union, America, and France, was damning.

Reams of unseen footage of the Holocaust and other Nazi crimes in occupied Europe were shown to the court.

The Soviets called on two Holocaust survivors for eye-witness testimony – Abraham Sutzkever and Samuel Rajzman, who had been in the Treblinka death camp.

Under the impact of this horrific evidence, the trial evolved from its original focus on Nazi crimes of aggression – the unprovoked invasion of several different countries since 1939 – to the Holocaust, which was identified in terms of two new categories of crime deployed for the first time at Nuremberg: crimes against humanity and genocide.

In September 1946, the Tribunal delivered its verdict: twelve of the defendants, including Göring and Ribbentrop, were sentenced to death, and seven were imprisoned.

Even before the Nuremberg Trials ended, the conditions which had made it possible began to fall apart. Over 1945-46, the Western Allies and the USSR increasingly became enemies as the Cold War got underway.

But the achievement of the Tribunal couldn’t be undone. The Nuremberg Charter and the verdict against the Nazi defendants were both soon recognised by the new

United Nations as principles of international law.

In the future, “I was just following orders” would not be enough.