Like a Memory Lost: The Life and Work of John Clare

Posted by Tom on 24th Jul 2022

John Clare is now one of England's best-loved poets, but for a long time he was almost entirely forgotten

The literary canon has always had its gaps and prejudices.

Wealthy white men have long taken centre stage, while workers, women, and people of colour have been marginalised and ignored.

Of course, in recent years, great efforts have been made to reset the balance.

Despite a reactionary backlash from alt-right culture warriors, syllabuses have been rewritten to bring these marginalised figures back into focus: writers whose work desperately deserves our attention.

Enter, stage left: the 'peasant poet' John Clare.

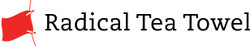

John Clare's poem "I Am!" was written during his stay in Northampton General Lunatic Asylum

Click to view our John Clare tea towel

Clare is now recognised as one of the greatest poets ever to write in the English language. But he hasn't always been so well-known.

In fact, until the mid 20th century, Clare's work was largely neglected – so much so that he’s often referred to as ‘the almost forgotten poet’.

Born into a labouring family in rural Northamptonshire in 1793, Clare’s world was a far cry from the London literary establishment of his day.

Both of his parents were illiterate, and he worked as an agricultural labourer throughout his childhood.

Though his education was patchy, Clare attended a night-school in his teens and began to write poems and sonnets inspired by the work of his favourite writers.

Poetry, for Clare, was a hobby - not a serious pursuit.

It wasn’t until his parents were threatened with eviction that Clare realised he might be able to sell his poems for money.

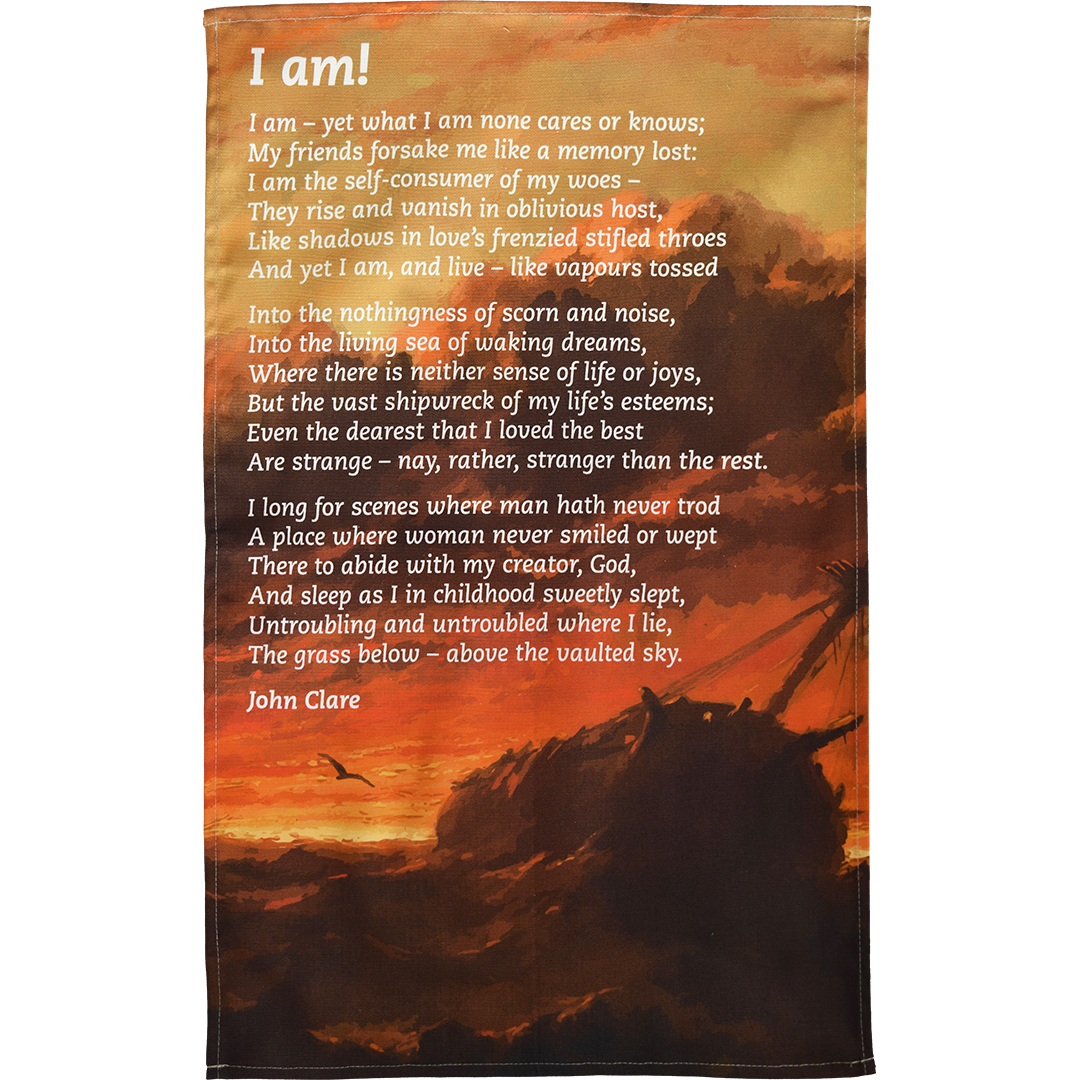

Though long-overlooked, John Clare has now taken his rightful place among Romantic poets like Percy Bysshe Shelley

Click to view our Percy Bysshe Shelley

Clare's first book, Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery, was published in 1820 by Taylor & Hessey of Fleet Street.

It was a hit: it sold over three thousand copies and went through four editions in the first year alone.

That may not seem much compared to the latest Sally Rooney, but for a book of poems back then it was pretty good going!

Clare quickly became an unlikely celebrity.

In the words of Frederick Martin, Clare's first biographer:

"There was no limit to the applause bestowed upon Clare, unanimous in their admiration of a poetical genius coming before them in the humble garb of a farm labourer."

But Clare's fame shouldn't come as a huge surprise.

After all, the literary establishment had long fetishised the idea of rural poverty and 'authenticity', and publishers were crying out for a so-called 'peasant poet' - an untaught genius to emerge shepherd-like from the countryside, spinning verses.

And Clare fitted the bill.

But his fame wouldn't last long. He published four more books in his life, all of which were financial failures - despite the fact that his poetry was maturing.

So what happened? How did Clare go so quickly from literary rising star to neglected poet?

It seems the public's enthusiasm for this eccentric 'peasant poet' didn't last long: every new book he wrote received less attention than the last.

All this inevitably took its toll.

Failing to succeed as a poet and struggling to pay his bills, Clare's mind grew increasingly unsettled.

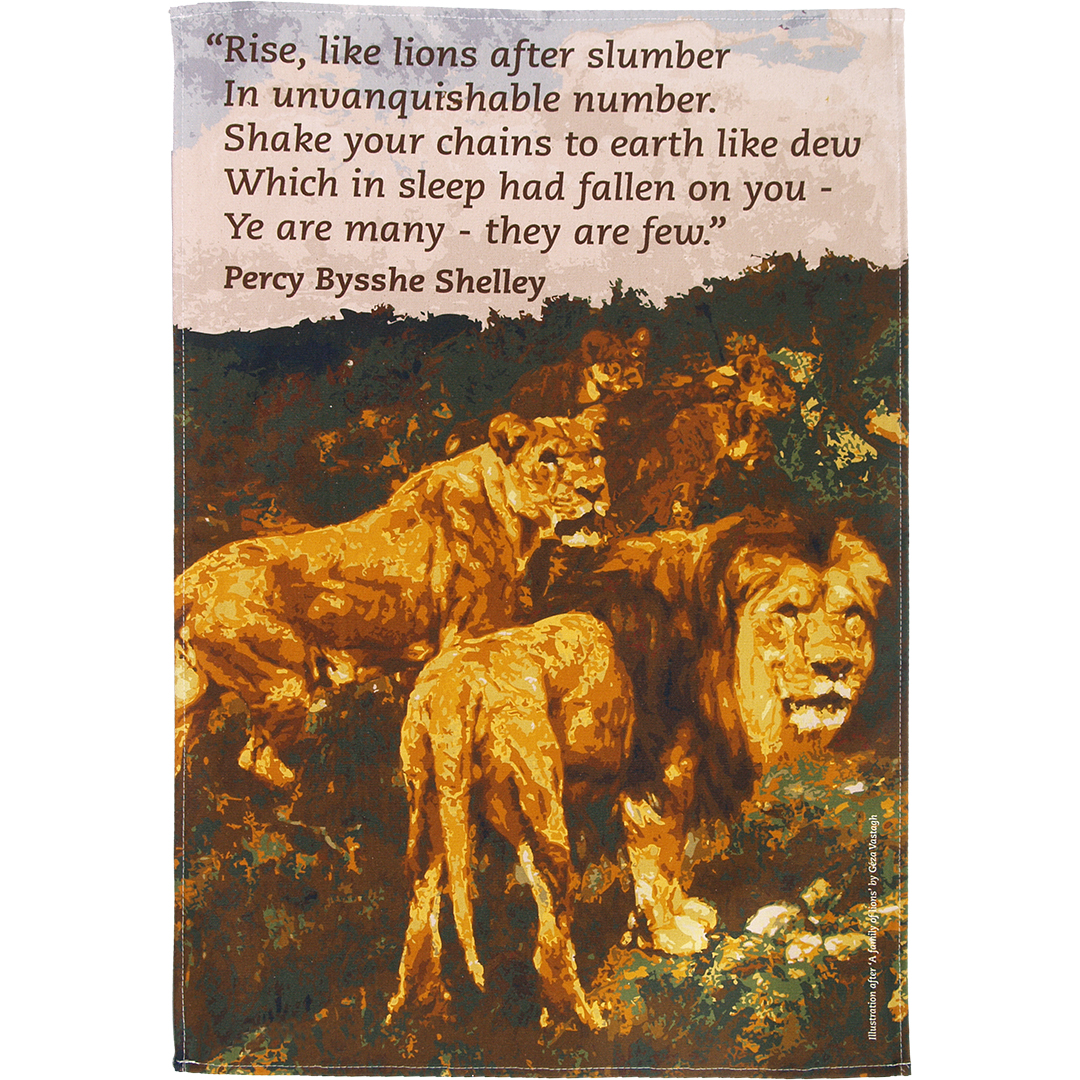

Olaudah Equiano is another great writer of the age who remained in obscurity until relatively recently

Click to view our Olaudah Equiano tea towel

In 1837, on the advice of his publisher, Clare checked himself into a private asylum in Epping Forest.

At this point, he was reportedly 'full of many strange delusions' - sometimes he thought he was a prize-winning boxer, other times he claimed to be the dead Lord Byron.

Then, in July 1841, Clare left the asylum in Epping Forest and walked 80 miles back to his home in Northamptonshire, eating grass by the roadside to stave off the hunger.

By the end of the year, he'd been certified insane and committed to the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum.

This is where he would spend the rest of his life.

It's also where he would write some of his most famous and celebrated poems, including "I Am!" - the poem featured on our new

John Clare tea towel.

It's a poem of extreme anguish: his friends have forsaken him 'like a memory lost', and his name has been forgotten.

And yet, it's also an assertion of selfhood and individuality in the face of this anguish.

I am, I am, I am, the poet says, as if refusing to be erased entirely from literary memory.

Clare died at the age of 71, in 1864. His burial request - that his gravestone should read 'Here Rest the Hope and Ashes of John Clare' - was ignored.

It wasn't until the 1930s that interest in Clare's poetry was revived by editors John and Anne Tibble, who championed Clare's work and saved it from obscurity.

So why is Clare's story important?

Well, he was a working-class poet who wrote about the struggles of working-class life: the effects of industrialisation, the theft of common land through forcible enclosure, and the other violent changes brought about by the British ruling class.

But his legacy shows that marginalised voices like his can - and should be - championed and reinstated in the story of English literature.

Of course, Clare isn't the only writer to be erased from the history of Romanticism in Britain. There's still a very long way to go.

Take Dorothy Wordsworth, whose journals are among the most beautiful books I have ever read.

For a long time, Dorothy was simply William's sister, and it's only recently that her work has been considered valuable in its own right.

Or Anna Laetitia Barbauld, an English poet and essayist whose work was largely forgotten until feminist critics in the 1980s sought to re-emphasise her importance.

Or

Olaudah Equiano, the black abolitionist whose memoir depicting the horrors helped to turn the tide in the campaign for abolition.

While

Wilberforce has been a household name for decades, Equiano's autobiography was out of print until the late 20th century.

At Radical Tea Towel, these are the sorts of people we want to champion.

I like to think that when John Clare says "I Am!" he's speaking not just for himself, but for all the outcasts and marginalised voices - asserting everyone's right to exist and be heard.