Refusing Complicity: The Bravery of Sophie Scholl

Posted by Pete on 9th May 2022

“How can we expect righteousness to prevail when there is hardly anyone willing to give himself up individually to a righteous cause?”

Time and again, students have led the fight against oppression and totalitarianism.

They were in the vanguard of campaigns against the

US invasion of Vietnam. And in South Africa, black students played a key role in resisting apartheid.

In Nazi Germany, too, the universities produced one of the few campaigns of wartime resistance to Hitler on the home front: The White Rose Movement.

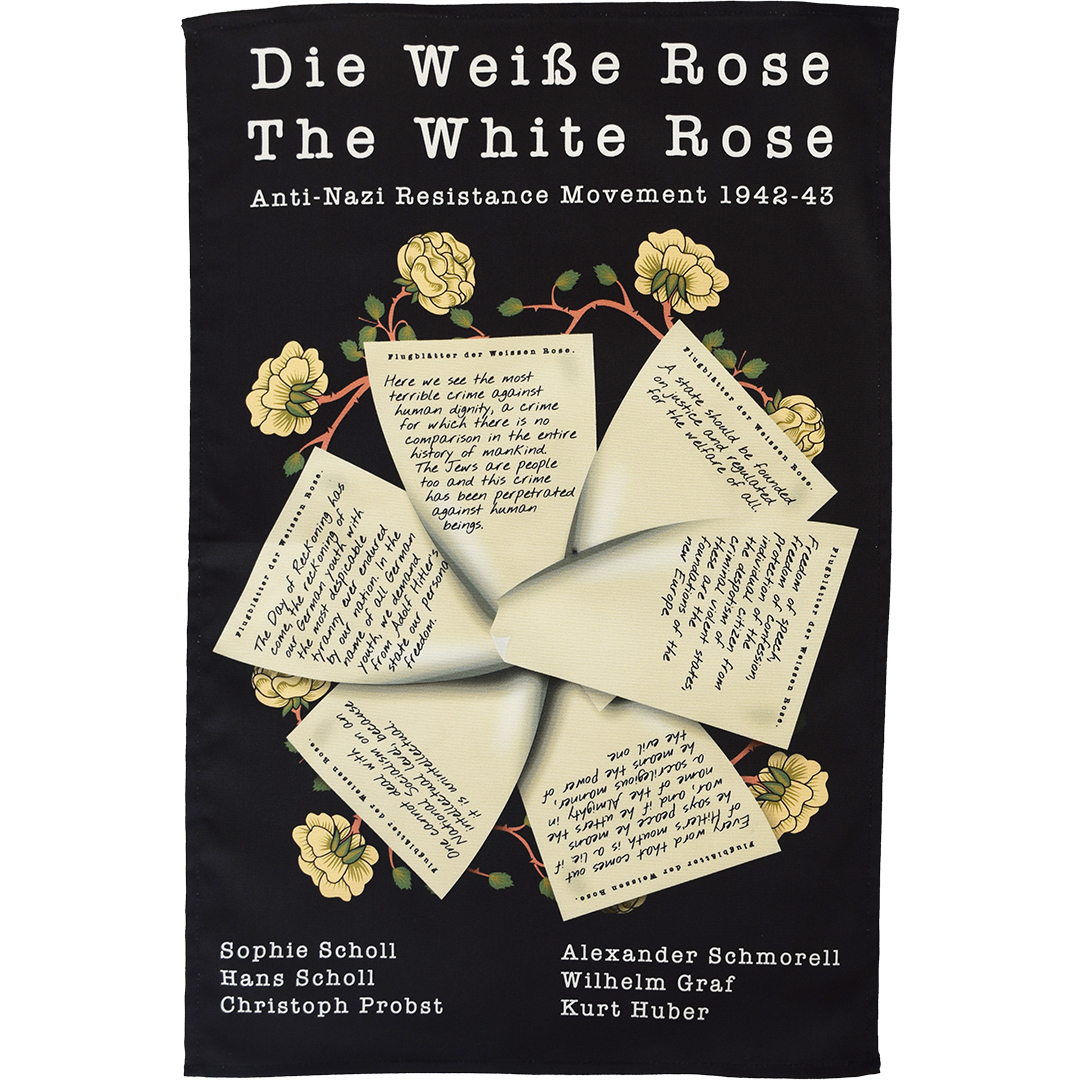

Our brand new White Rose tea towel, featuring several quotations from their pamphlets shaped in the symbol of a rose

Click to view our White Rose tea towel

Universities in Germany have a long and healthy tradition of radical activism.

Students and professors had been in the vanguard of the

liberal revolution of 1848. And it was German universities which had produced radical intellectuals like Karl Marx.

But the Nazis meant to turn the German education system, like every aspect of society, into a channel of fascist education under the total control of Hitler’s regime. And they were largely successful.

By the time Germany invaded Poland in 1939, the universities were no longer a promising site of resistance.

The totalitarian system built by the Nazis over the previous six years, coupled with the conscription of millions of young Germans to fight the war, led to an almost complete absence of student dissent.

But Sophie Scholl was one of the heroic exceptions.

Sophie Scholl pictured in 1942

Born today in 1921, Sophia Magdalena Scholl was a student of biology and philosophy at the University of Munich. Her brother, Hans, was a student too – though he also spent time as a medic on the Eastern Front.

By 1941, Hans had become radically disillusioned with the Nazi regime. In June 1942, with a group of like-minded friends, he launched the

White Rose Movement at Munich, secretly printing and distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets.

Sophie joined up as soon as she learned about the project.

Like

other opponents of Hitler, Sophie and Hans were motivated in significant part by religion. Their Catholic readings were a big influence. But so, too, were their parents: their father was a vocal opponent of Nazism and had been jailed in 1942 for openly criticising Adolf Hitler.

The clandestine efforts of the White Rose activists never became a mass movement – the Nazi regime was designed to prevent that happening.

But smaller numbers required greater courage, which Sophie Scholl had in abundance.

The most prominent woman in a group of mostly men, her self-sacrifice was remarkable.

When Sophie and Hans were arrested by the Gestapo in February 1943, she attempted to take full responsibility for the pamphleteering in order to protect the other members of the group.

On 22 February, along with her White Rose comrades, Sophie faced her execution with singular bravery:

“It is such a splendid sunny day, and I have to go… What does my death matter if by our acts thousands are warned and alerted?”

She was just 21 years old.

Another activist murdered by the German state, Rosa Luxemburg led the Spartacist Uprising in 1919

Click to view our Rosa Luxemburg tea towel

Sophie Scholl’s story is not one of victory, at least not in a direct sense.

While student movements for Civil Rights in the U.S. and South Africa managed to force through governmental change, the Nazi regime survived the White Rose resistance.

When Sophie Scholl came on the scene, the major forces of resistance in Nazi Germany had been silenced. Opposition political parties were outlawed. Socialists and communists had been imprisoned and even murdered

In this hopeless context, the brave defiance of the White Rose is all the more remarkable.

To risk certain death with little chance of success. To refuse complicity, when complicity is your only chance of survival. That’s what radicalism means: to resist because resistance is a moral imperative.

There’s a lot we can learn from courage like that.